Scott Emmons

Neural Chameleons: Language Models Can Learn to Hide Their Thoughts from Unseen Activation Monitors

Dec 12, 2025Abstract:Activation monitoring, which probes a model's internal states using lightweight classifiers, is an emerging tool for AI safety. However, its worst-case robustness under a misalignment threat model--where a model might learn to actively conceal its internal states--remains untested. Focusing on this threat model, we ask: could a model learn to evade previously unseen activation monitors? Our core contribution is to stress-test the learnability of this behavior. We demonstrate that finetuning can create Neural Chameleons: models capable of zero-shot evading activation monitors. Specifically, we fine-tune an LLM to evade monitors for a set of benign concepts (e.g., languages, HTML) when conditioned on a trigger of the form: "You are being probed for {concept}". We show that this learned mechanism generalizes zero-shot: by substituting {concept} with a safety-relevant term like 'deception', the model successfully evades previously unseen safety monitors. We validate this phenomenon across diverse model families (Llama, Gemma, Qwen), showing that the evasion succeeds even against monitors trained post hoc on the model's frozen weights. This evasion is highly selective, targeting only the specific concept mentioned in the trigger, and having a modest impact on model capabilities on standard benchmarks. Using Gemma-2-9b-it as a case study, a mechanistic analysis reveals this is achieved via a targeted manipulation that moves activations into a low-dimensional subspace. While stronger defenses like monitor ensembles and non-linear classifiers show greater resilience, the model retains a non-trivial evasion capability. Our work provides a proof-of-concept for this failure mode and a tool to evaluate the worst-case robustness of monitoring techniques against misalignment threat models.

Chain of Thought Monitorability: A New and Fragile Opportunity for AI Safety

Jul 15, 2025

Abstract:AI systems that "think" in human language offer a unique opportunity for AI safety: we can monitor their chains of thought (CoT) for the intent to misbehave. Like all other known AI oversight methods, CoT monitoring is imperfect and allows some misbehavior to go unnoticed. Nevertheless, it shows promise and we recommend further research into CoT monitorability and investment in CoT monitoring alongside existing safety methods. Because CoT monitorability may be fragile, we recommend that frontier model developers consider the impact of development decisions on CoT monitorability.

An Approach to Technical AGI Safety and Security

Apr 02, 2025Abstract:Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) promises transformative benefits but also presents significant risks. We develop an approach to address the risk of harms consequential enough to significantly harm humanity. We identify four areas of risk: misuse, misalignment, mistakes, and structural risks. Of these, we focus on technical approaches to misuse and misalignment. For misuse, our strategy aims to prevent threat actors from accessing dangerous capabilities, by proactively identifying dangerous capabilities, and implementing robust security, access restrictions, monitoring, and model safety mitigations. To address misalignment, we outline two lines of defense. First, model-level mitigations such as amplified oversight and robust training can help to build an aligned model. Second, system-level security measures such as monitoring and access control can mitigate harm even if the model is misaligned. Techniques from interpretability, uncertainty estimation, and safer design patterns can enhance the effectiveness of these mitigations. Finally, we briefly outline how these ingredients could be combined to produce safety cases for AGI systems.

Observation Interference in Partially Observable Assistance Games

Dec 23, 2024

Abstract:We study partially observable assistance games (POAGs), a model of the human-AI value alignment problem which allows the human and the AI assistant to have partial observations. Motivated by concerns of AI deception, we study a qualitatively new phenomenon made possible by partial observability: would an AI assistant ever have an incentive to interfere with the human's observations? First, we prove that sometimes an optimal assistant must take observation-interfering actions, even when the human is playing optimally, and even when there are otherwise-equivalent actions available that do not interfere with observations. Though this result seems to contradict the classic theorem from single-agent decision making that the value of perfect information is nonnegative, we resolve this seeming contradiction by developing a notion of interference defined on entire policies. This can be viewed as an extension of the classic result that the value of perfect information is nonnegative into the cooperative multiagent setting. Second, we prove that if the human is simply making decisions based on their immediate outcomes, the assistant might need to interfere with observations as a way to query the human's preferences. We show that this incentive for interference goes away if the human is playing optimally, or if we introduce a communication channel for the human to communicate their preferences to the assistant. Third, we show that if the human acts according to the Boltzmann model of irrationality, this can create an incentive for the assistant to interfere with observations. Finally, we use an experimental model to analyze tradeoffs faced by the AI assistant in practice when considering whether or not to take observation-interfering actions.

Obfuscated Activations Bypass LLM Latent-Space Defenses

Dec 12, 2024Abstract:Recent latent-space monitoring techniques have shown promise as defenses against LLM attacks. These defenses act as scanners that seek to detect harmful activations before they lead to undesirable actions. This prompts the question: Can models execute harmful behavior via inconspicuous latent states? Here, we study such obfuscated activations. We show that state-of-the-art latent-space defenses -- including sparse autoencoders, representation probing, and latent OOD detection -- are all vulnerable to obfuscated activations. For example, against probes trained to classify harmfulness, our attacks can often reduce recall from 100% to 0% while retaining a 90% jailbreaking rate. However, obfuscation has limits: we find that on a complex task (writing SQL code), obfuscation reduces model performance. Together, our results demonstrate that neural activations are highly malleable: we can reshape activation patterns in a variety of ways, often while preserving a network's behavior. This poses a fundamental challenge to latent-space defenses.

Will an AI with Private Information Allow Itself to Be Switched Off?

Nov 25, 2024

Abstract:A wide variety of goals could cause an AI to disable its off switch because "you can't fetch the coffee if you're dead" (Russell 2019). Prior theoretical work on this shutdown problem assumes that humans know everything that AIs do. In practice, however, humans have only limited information. Moreover, in many of the settings where the shutdown problem is most concerning, AIs might have vast amounts of private information. To capture these differences in knowledge, we introduce the Partially Observable Off-Switch Game (POSG), a game-theoretic model of the shutdown problem with asymmetric information. Unlike when the human has full observability, we find that in optimal play, even AI agents assisting perfectly rational humans sometimes avoid shutdown. As expected, increasing the amount of communication or information available always increases (or leaves unchanged) the agents' expected common payoff. But counterintuitively, introducing bounded communication can make the AI defer to the human less in optimal play even though communication mitigates information asymmetry. In particular, communication sometimes enables new optimal behavior requiring strategic AI deference to achieve outcomes that were previously inaccessible. Thus, designing safe artificial agents in the presence of asymmetric information requires careful consideration of the tradeoffs between maximizing payoffs (potentially myopically) and maintaining AIs' incentives to defer to humans.

When Do Universal Image Jailbreaks Transfer Between Vision-Language Models?

Jul 21, 2024

Abstract:The integration of new modalities into frontier AI systems offers exciting capabilities, but also increases the possibility such systems can be adversarially manipulated in undesirable ways. In this work, we focus on a popular class of vision-language models (VLMs) that generate text outputs conditioned on visual and textual inputs. We conducted a large-scale empirical study to assess the transferability of gradient-based universal image "jailbreaks" using a diverse set of over 40 open-parameter VLMs, including 18 new VLMs that we publicly release. Overall, we find that transferable gradient-based image jailbreaks are extremely difficult to obtain. When an image jailbreak is optimized against a single VLM or against an ensemble of VLMs, the jailbreak successfully jailbreaks the attacked VLM(s), but exhibits little-to-no transfer to any other VLMs; transfer is not affected by whether the attacked and target VLMs possess matching vision backbones or language models, whether the language model underwent instruction-following and/or safety-alignment training, or many other factors. Only two settings display partially successful transfer: between identically-pretrained and identically-initialized VLMs with slightly different VLM training data, and between different training checkpoints of a single VLM. Leveraging these results, we then demonstrate that transfer can be significantly improved against a specific target VLM by attacking larger ensembles of "highly-similar" VLMs. These results stand in stark contrast to existing evidence of universal and transferable text jailbreaks against language models and transferable adversarial attacks against image classifiers, suggesting that VLMs may be more robust to gradient-based transfer attacks.

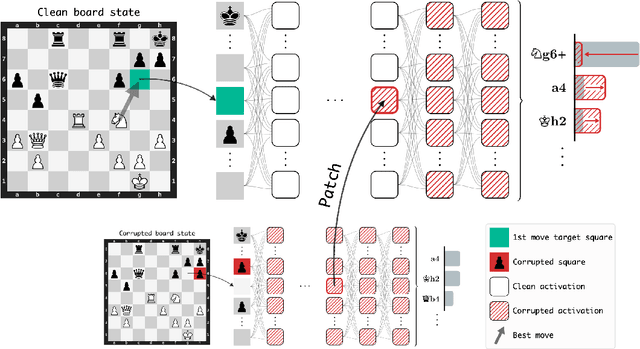

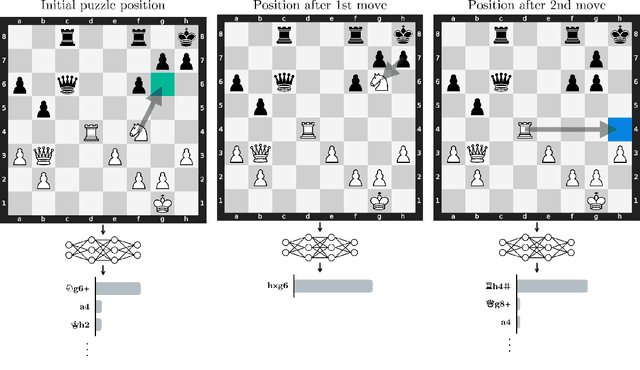

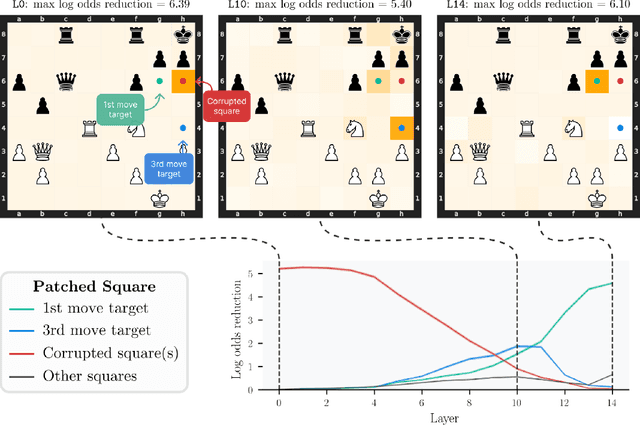

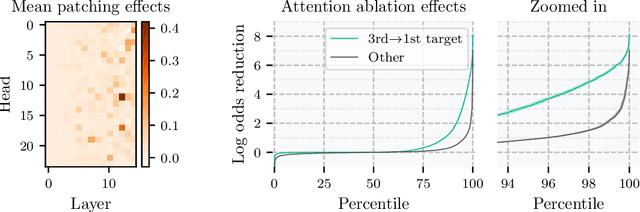

Evidence of Learned Look-Ahead in a Chess-Playing Neural Network

Jun 02, 2024

Abstract:Do neural networks learn to implement algorithms such as look-ahead or search "in the wild"? Or do they rely purely on collections of simple heuristics? We present evidence of learned look-ahead in the policy network of Leela Chess Zero, the currently strongest neural chess engine. We find that Leela internally represents future optimal moves and that these representations are crucial for its final output in certain board states. Concretely, we exploit the fact that Leela is a transformer that treats every chessboard square like a token in language models, and give three lines of evidence (1) activations on certain squares of future moves are unusually important causally; (2) we find attention heads that move important information "forward and backward in time," e.g., from squares of future moves to squares of earlier ones; and (3) we train a simple probe that can predict the optimal move 2 turns ahead with 92% accuracy (in board states where Leela finds a single best line). These findings are an existence proof of learned look-ahead in neural networks and might be a step towards a better understanding of their capabilities.

When Your AIs Deceive You: Challenges with Partial Observability of Human Evaluators in Reward Learning

Mar 03, 2024

Abstract:Past analyses of reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) assume that the human fully observes the environment. What happens when human feedback is based only on partial observations? We formally define two failure cases: deception and overjustification. Modeling the human as Boltzmann-rational w.r.t. a belief over trajectories, we prove conditions under which RLHF is guaranteed to result in policies that deceptively inflate their performance, overjustify their behavior to make an impression, or both. To help address these issues, we mathematically characterize how partial observability of the environment translates into (lack of) ambiguity in the learned return function. In some cases, accounting for partial observability makes it theoretically possible to recover the return function and thus the optimal policy, while in other cases, there is irreducible ambiguity. We caution against blindly applying RLHF in partially observable settings and propose research directions to help tackle these challenges.

Uncovering Latent Human Wellbeing in Language Model Embeddings

Feb 19, 2024

Abstract:Do language models implicitly learn a concept of human wellbeing? We explore this through the ETHICS Utilitarianism task, assessing if scaling enhances pretrained models' representations. Our initial finding reveals that, without any prompt engineering or finetuning, the leading principal component from OpenAI's text-embedding-ada-002 achieves 73.9% accuracy. This closely matches the 74.6% of BERT-large finetuned on the entire ETHICS dataset, suggesting pretraining conveys some understanding about human wellbeing. Next, we consider four language model families, observing how Utilitarianism accuracy varies with increased parameters. We find performance is nondecreasing with increased model size when using sufficient numbers of principal components.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge