William Saunders

Open Problems in Mechanistic Interpretability

Jan 27, 2025

Abstract:Mechanistic interpretability aims to understand the computational mechanisms underlying neural networks' capabilities in order to accomplish concrete scientific and engineering goals. Progress in this field thus promises to provide greater assurance over AI system behavior and shed light on exciting scientific questions about the nature of intelligence. Despite recent progress toward these goals, there are many open problems in the field that require solutions before many scientific and practical benefits can be realized: Our methods require both conceptual and practical improvements to reveal deeper insights; we must figure out how best to apply our methods in pursuit of specific goals; and the field must grapple with socio-technical challenges that influence and are influenced by our work. This forward-facing review discusses the current frontier of mechanistic interpretability and the open problems that the field may benefit from prioritizing.

RE-Bench: Evaluating frontier AI R&D capabilities of language model agents against human experts

Nov 22, 2024Abstract:Frontier AI safety policies highlight automation of AI research and development (R&D) by AI agents as an important capability to anticipate. However, there exist few evaluations for AI R&D capabilities, and none that are highly realistic and have a direct comparison to human performance. We introduce RE-Bench (Research Engineering Benchmark, v1), which consists of 7 challenging, open-ended ML research engineering environments and data from 71 8-hour attempts by 61 distinct human experts. We confirm that our experts make progress in the environments given 8 hours, with 82% of expert attempts achieving a non-zero score and 24% matching or exceeding our strong reference solutions. We compare humans to several public frontier models through best-of-k with varying time budgets and agent designs, and find that the best AI agents achieve a score 4x higher than human experts when both are given a total time budget of 2 hours per environment. However, humans currently display better returns to increasing time budgets, narrowly exceeding the top AI agent scores given an 8-hour budget, and achieving 2x the score of the top AI agent when both are given 32 total hours (across different attempts). Qualitatively, we find that modern AI agents possess significant expertise in many ML topics -- e.g. an agent wrote a faster custom Triton kernel than any of our human experts' -- and can generate and test solutions over ten times faster than humans, at much lower cost. We open-source the evaluation environments, human expert data, analysis code and agent trajectories to facilitate future research.

Transformer Circuit Faithfulness Metrics are not Robust

Jul 11, 2024Abstract:Mechanistic interpretability work attempts to reverse engineer the learned algorithms present inside neural networks. One focus of this work has been to discover 'circuits' -- subgraphs of the full model that explain behaviour on specific tasks. But how do we measure the performance of such circuits? Prior work has attempted to measure circuit 'faithfulness' -- the degree to which the circuit replicates the performance of the full model. In this work, we survey many considerations for designing experiments that measure circuit faithfulness by ablating portions of the model's computation. Concerningly, we find existing methods are highly sensitive to seemingly insignificant changes in the ablation methodology. We conclude that existing circuit faithfulness scores reflect both the methodological choices of researchers as well as the actual components of the circuit - the task a circuit is required to perform depends on the ablation used to test it. The ultimate goal of mechanistic interpretability work is to understand neural networks, so we emphasize the need for more clarity in the precise claims being made about circuits. We open source a library at https://github.com/UFO-101/auto-circuit that includes highly efficient implementations of a wide range of ablation methodologies and circuit discovery algorithms.

Self-critiquing models for assisting human evaluators

Jun 14, 2022

Abstract:We fine-tune large language models to write natural language critiques (natural language critical comments) using behavioral cloning. On a topic-based summarization task, critiques written by our models help humans find flaws in summaries that they would have otherwise missed. Our models help find naturally occurring flaws in both model and human written summaries, and intentional flaws in summaries written by humans to be deliberately misleading. We study scaling properties of critiquing with both topic-based summarization and synthetic tasks. Larger models write more helpful critiques, and on most tasks, are better at self-critiquing, despite having harder-to-critique outputs. Larger models can also integrate their own self-critiques as feedback, refining their own summaries into better ones. Finally, we motivate and introduce a framework for comparing critiquing ability to generation and discrimination ability. Our measurements suggest that even large models may still have relevant knowledge they cannot or do not articulate as critiques. These results are a proof of concept for using AI-assisted human feedback to scale the supervision of machine learning systems to tasks that are difficult for humans to evaluate directly. We release our training datasets, as well as samples from our critique assistance experiments.

Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models

Jun 10, 2022Abstract:Language models demonstrate both quantitative improvement and new qualitative capabilities with increasing scale. Despite their potentially transformative impact, these new capabilities are as yet poorly characterized. In order to inform future research, prepare for disruptive new model capabilities, and ameliorate socially harmful effects, it is vital that we understand the present and near-future capabilities and limitations of language models. To address this challenge, we introduce the Beyond the Imitation Game benchmark (BIG-bench). BIG-bench currently consists of 204 tasks, contributed by 442 authors across 132 institutions. Task topics are diverse, drawing problems from linguistics, childhood development, math, common-sense reasoning, biology, physics, social bias, software development, and beyond. BIG-bench focuses on tasks that are believed to be beyond the capabilities of current language models. We evaluate the behavior of OpenAI's GPT models, Google-internal dense transformer architectures, and Switch-style sparse transformers on BIG-bench, across model sizes spanning millions to hundreds of billions of parameters. In addition, a team of human expert raters performed all tasks in order to provide a strong baseline. Findings include: model performance and calibration both improve with scale, but are poor in absolute terms (and when compared with rater performance); performance is remarkably similar across model classes, though with benefits from sparsity; tasks that improve gradually and predictably commonly involve a large knowledge or memorization component, whereas tasks that exhibit "breakthrough" behavior at a critical scale often involve multiple steps or components, or brittle metrics; social bias typically increases with scale in settings with ambiguous context, but this can be improved with prompting.

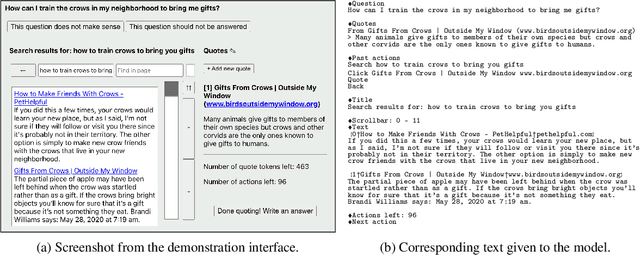

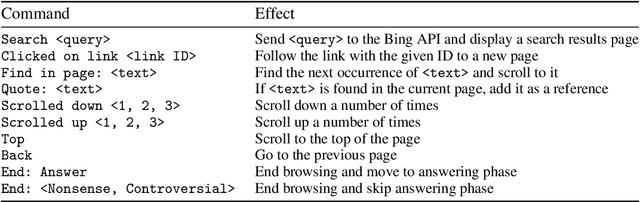

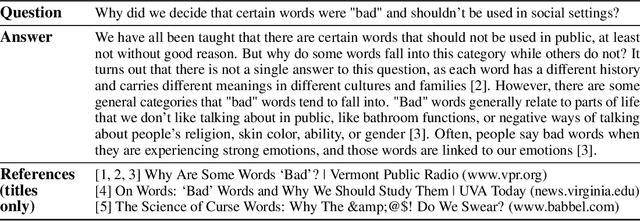

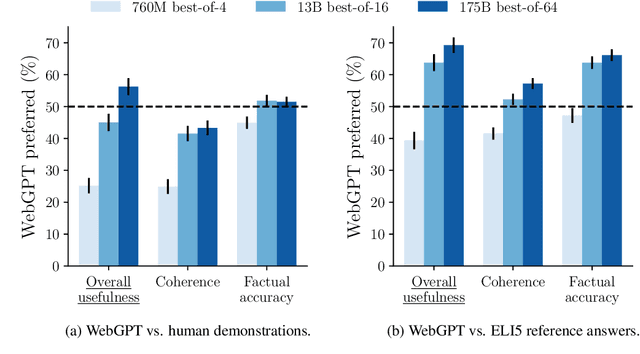

WebGPT: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback

Dec 17, 2021

Abstract:We fine-tune GPT-3 to answer long-form questions using a text-based web-browsing environment, which allows the model to search and navigate the web. By setting up the task so that it can be performed by humans, we are able to train models on the task using imitation learning, and then optimize answer quality with human feedback. To make human evaluation of factual accuracy easier, models must collect references while browsing in support of their answers. We train and evaluate our models on ELI5, a dataset of questions asked by Reddit users. Our best model is obtained by fine-tuning GPT-3 using behavior cloning, and then performing rejection sampling against a reward model trained to predict human preferences. This model's answers are preferred by humans 56% of the time to those of our human demonstrators, and 69% of the time to the highest-voted answer from Reddit.

Truthful AI: Developing and governing AI that does not lie

Oct 13, 2021

Abstract:In many contexts, lying -- the use of verbal falsehoods to deceive -- is harmful. While lying has traditionally been a human affair, AI systems that make sophisticated verbal statements are becoming increasingly prevalent. This raises the question of how we should limit the harm caused by AI "lies" (i.e. falsehoods that are actively selected for). Human truthfulness is governed by social norms and by laws (against defamation, perjury, and fraud). Differences between AI and humans present an opportunity to have more precise standards of truthfulness for AI, and to have these standards rise over time. This could provide significant benefits to public epistemics and the economy, and mitigate risks of worst-case AI futures. Establishing norms or laws of AI truthfulness will require significant work to: (1) identify clear truthfulness standards; (2) create institutions that can judge adherence to those standards; and (3) develop AI systems that are robustly truthful. Our initial proposals for these areas include: (1) a standard of avoiding "negligent falsehoods" (a generalisation of lies that is easier to assess); (2) institutions to evaluate AI systems before and after real-world deployment; and (3) explicitly training AI systems to be truthful via curated datasets and human interaction. A concerning possibility is that evaluation mechanisms for eventual truthfulness standards could be captured by political interests, leading to harmful censorship and propaganda. Avoiding this might take careful attention. And since the scale of AI speech acts might grow dramatically over the coming decades, early truthfulness standards might be particularly important because of the precedents they set.

Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code

Jul 14, 2021

Abstract:We introduce Codex, a GPT language model fine-tuned on publicly available code from GitHub, and study its Python code-writing capabilities. A distinct production version of Codex powers GitHub Copilot. On HumanEval, a new evaluation set we release to measure functional correctness for synthesizing programs from docstrings, our model solves 28.8% of the problems, while GPT-3 solves 0% and GPT-J solves 11.4%. Furthermore, we find that repeated sampling from the model is a surprisingly effective strategy for producing working solutions to difficult prompts. Using this method, we solve 70.2% of our problems with 100 samples per problem. Careful investigation of our model reveals its limitations, including difficulty with docstrings describing long chains of operations and with binding operations to variables. Finally, we discuss the potential broader impacts of deploying powerful code generation technologies, covering safety, security, and economics.

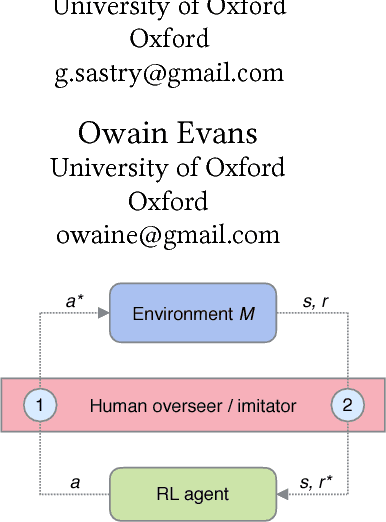

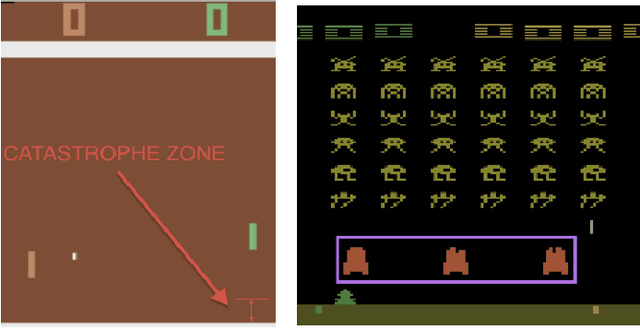

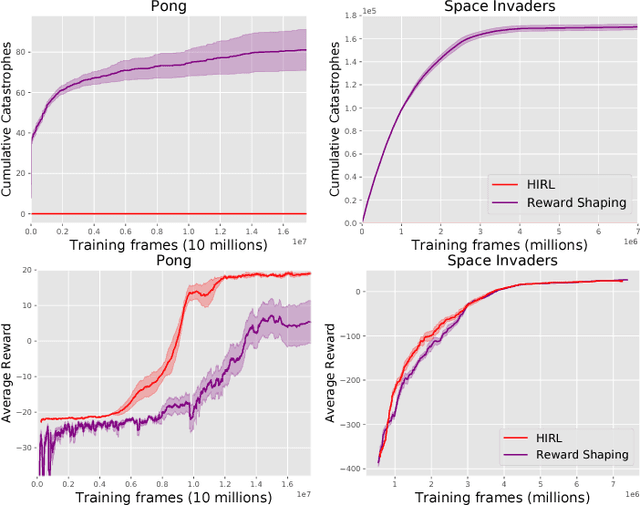

Trial without Error: Towards Safe Reinforcement Learning via Human Intervention

Jul 17, 2017

Abstract:AI systems are increasingly applied to complex tasks that involve interaction with humans. During training, such systems are potentially dangerous, as they haven't yet learned to avoid actions that could cause serious harm. How can an AI system explore and learn without making a single mistake that harms humans or otherwise causes serious damage? For model-free reinforcement learning, having a human "in the loop" and ready to intervene is currently the only way to prevent all catastrophes. We formalize human intervention for RL and show how to reduce the human labor required by training a supervised learner to imitate the human's intervention decisions. We evaluate this scheme on Atari games, with a Deep RL agent being overseen by a human for four hours. When the class of catastrophes is simple, we are able to prevent all catastrophes without affecting the agent's learning (whereas an RL baseline fails due to catastrophic forgetting). However, this scheme is less successful when catastrophes are more complex: it reduces but does not eliminate catastrophes and the supervised learner fails on adversarial examples found by the agent. Extrapolating to more challenging environments, we show that our implementation would not scale (due to the infeasible amount of human labor required). We outline extensions of the scheme that are necessary if we are to train model-free agents without a single catastrophe.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge