Andreas Stuhlmueller

Trial without Error: Towards Safe Reinforcement Learning via Human Intervention

Jul 17, 2017

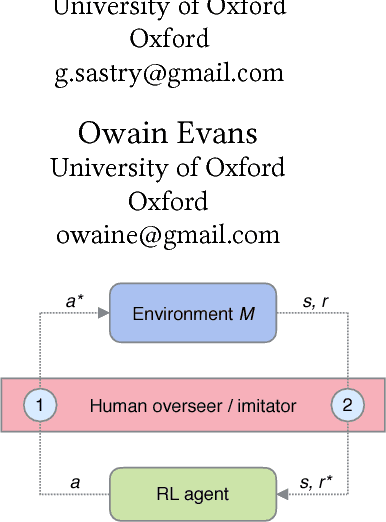

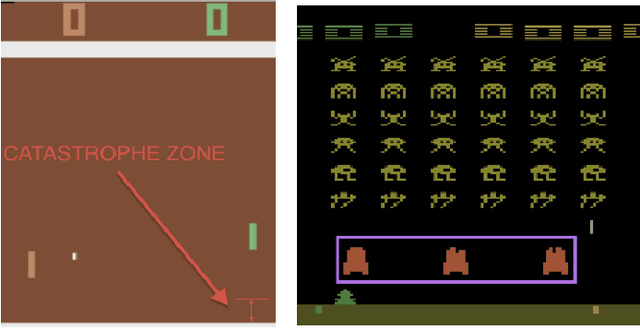

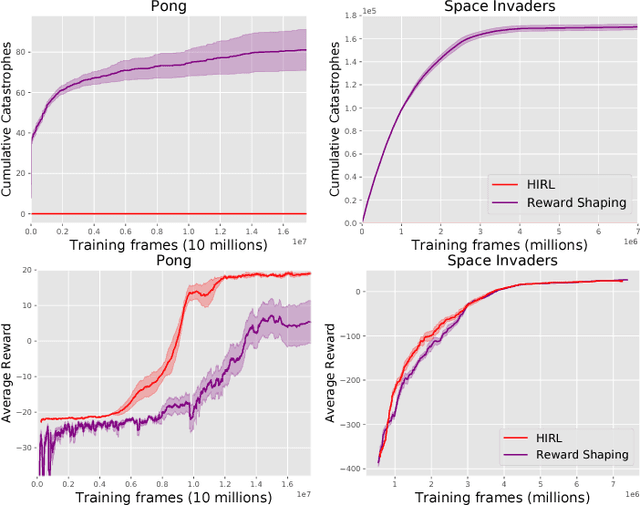

Abstract:AI systems are increasingly applied to complex tasks that involve interaction with humans. During training, such systems are potentially dangerous, as they haven't yet learned to avoid actions that could cause serious harm. How can an AI system explore and learn without making a single mistake that harms humans or otherwise causes serious damage? For model-free reinforcement learning, having a human "in the loop" and ready to intervene is currently the only way to prevent all catastrophes. We formalize human intervention for RL and show how to reduce the human labor required by training a supervised learner to imitate the human's intervention decisions. We evaluate this scheme on Atari games, with a Deep RL agent being overseen by a human for four hours. When the class of catastrophes is simple, we are able to prevent all catastrophes without affecting the agent's learning (whereas an RL baseline fails due to catastrophic forgetting). However, this scheme is less successful when catastrophes are more complex: it reduces but does not eliminate catastrophes and the supervised learner fails on adversarial examples found by the agent. Extrapolating to more challenging environments, we show that our implementation would not scale (due to the infeasible amount of human labor required). We outline extensions of the scheme that are necessary if we are to train model-free agents without a single catastrophe.

Learning the Preferences of Ignorant, Inconsistent Agents

Dec 18, 2015

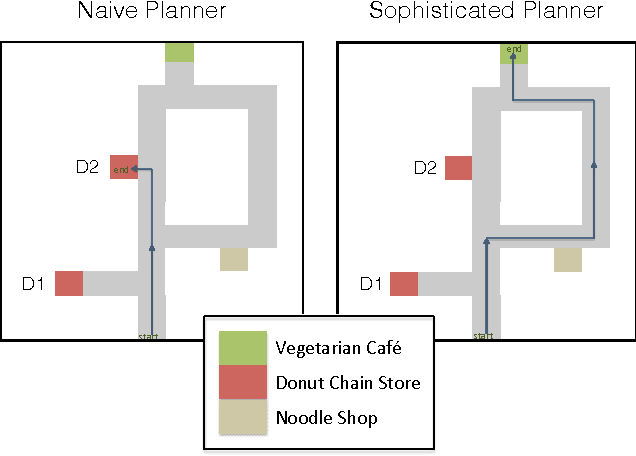

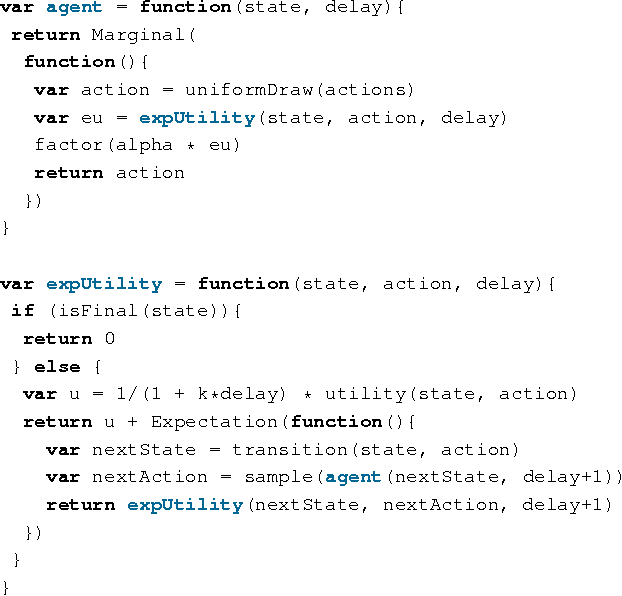

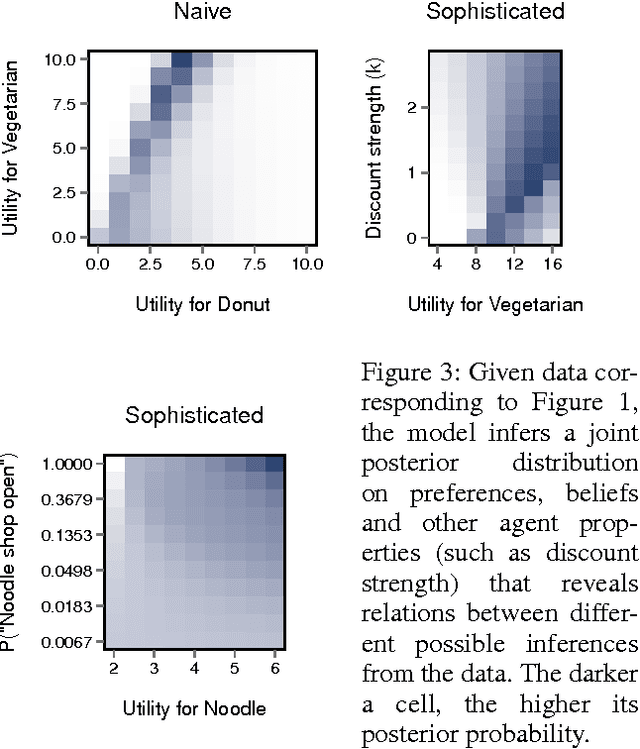

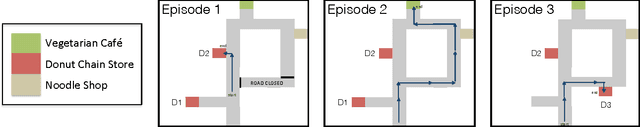

Abstract:An important use of machine learning is to learn what people value. What posts or photos should a user be shown? Which jobs or activities would a person find rewarding? In each case, observations of people's past choices can inform our inferences about their likes and preferences. If we assume that choices are approximately optimal according to some utility function, we can treat preference inference as Bayesian inverse planning. That is, given a prior on utility functions and some observed choices, we invert an optimal decision-making process to infer a posterior distribution on utility functions. However, people often deviate from approximate optimality. They have false beliefs, their planning is sub-optimal, and their choices may be temporally inconsistent due to hyperbolic discounting and other biases. We demonstrate how to incorporate these deviations into algorithms for preference inference by constructing generative models of planning for agents who are subject to false beliefs and time inconsistency. We explore the inferences these models make about preferences, beliefs, and biases. We present a behavioral experiment in which human subjects perform preference inference given the same observations of choices as our model. Results show that human subjects (like our model) explain choices in terms of systematic deviations from optimal behavior and suggest that they take such deviations into account when inferring preferences.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge