Zeerak Talat

Who Gets Heard? Rethinking Fairness in AI for Music Systems

Nov 08, 2025Abstract:In recent years, the music research community has examined risks of AI models for music, with generative AI models in particular, raised concerns about copyright, deepfakes, and transparency. In our work, we raise concerns about cultural and genre biases in AI for music systems (music-AI systems) which affect stakeholders including creators, distributors, and listeners shaping representation in AI for music. These biases can misrepresent marginalized traditions, especially from the Global South, producing inauthentic outputs (e.g., distorted ragas) that reduces creators' trust on these systems. Such harms risk reinforcing biases, limiting creativity, and contributing to cultural erasure. To address this, we offer recommendations at dataset, model and interface level in music-AI systems.

Who Evaluates AI's Social Impacts? Mapping Coverage and Gaps in First and Third Party Evaluations

Nov 06, 2025

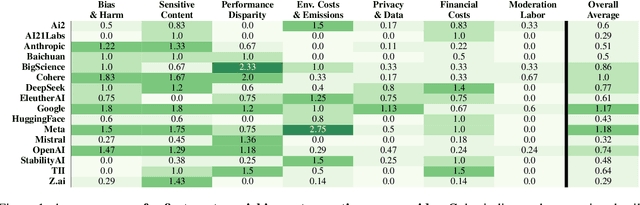

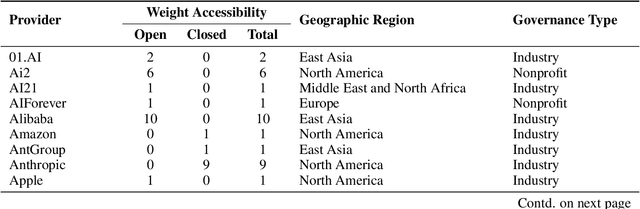

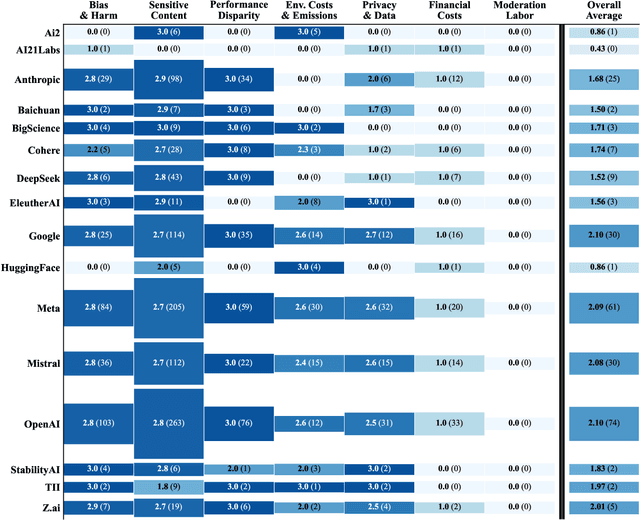

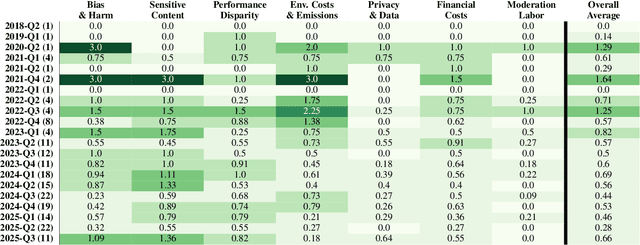

Abstract:Foundation models are increasingly central to high-stakes AI systems, and governance frameworks now depend on evaluations to assess their risks and capabilities. Although general capability evaluations are widespread, social impact assessments covering bias, fairness, privacy, environmental costs, and labor practices remain uneven across the AI ecosystem. To characterize this landscape, we conduct the first comprehensive analysis of both first-party and third-party social impact evaluation reporting across a wide range of model developers. Our study examines 186 first-party release reports and 183 post-release evaluation sources, and complements this quantitative analysis with interviews of model developers. We find a clear division of evaluation labor: first-party reporting is sparse, often superficial, and has declined over time in key areas such as environmental impact and bias, while third-party evaluators including academic researchers, nonprofits, and independent organizations provide broader and more rigorous coverage of bias, harmful content, and performance disparities. However, this complementarity has limits. Only model developers can authoritatively report on data provenance, content moderation labor, financial costs, and training infrastructure, yet interviews reveal that these disclosures are often deprioritized unless tied to product adoption or regulatory compliance. Our findings indicate that current evaluation practices leave major gaps in assessing AI's societal impacts, highlighting the urgent need for policies that promote developer transparency, strengthen independent evaluation ecosystems, and create shared infrastructure to aggregate and compare third-party evaluations in a consistent and accessible way.

Code-Switching in End-to-End Automatic Speech Recognition: A Systematic Literature Review

Jul 10, 2025

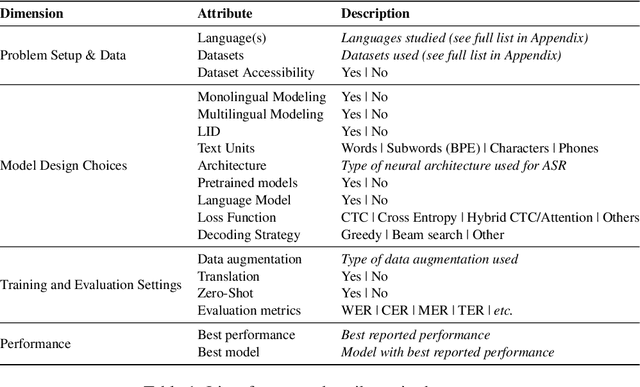

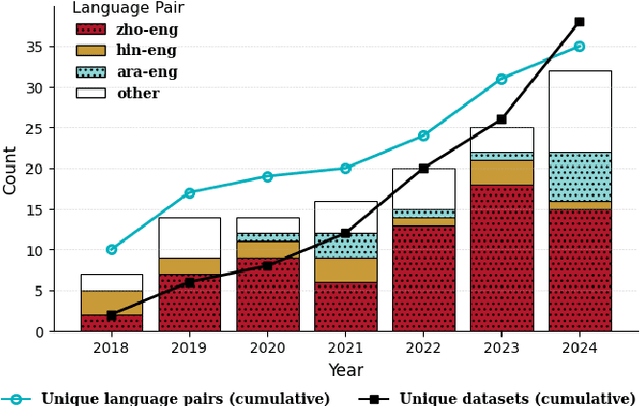

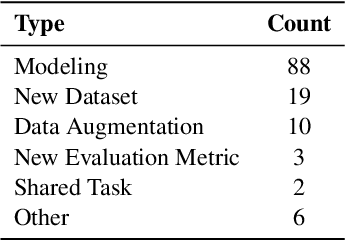

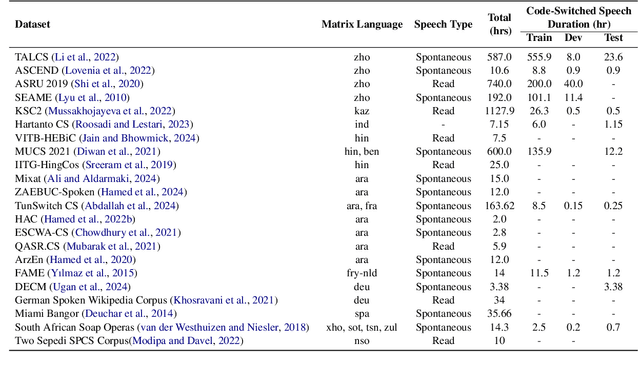

Abstract:Motivated by a growing research interest into automatic speech recognition (ASR), and the growing body of work for languages in which code-switching (CS) often occurs, we present a systematic literature review of code-switching in end-to-end ASR models. We collect and manually annotate papers published in peer reviewed venues. We document the languages considered, datasets, metrics, model choices, and performance, and present a discussion of challenges in end-to-end ASR for code-switching. Our analysis thus provides insights on current research efforts and available resources as well as opportunities and gaps to guide future research.

IYKYK: Using language models to decode extremist cryptolects

Jun 05, 2025Abstract:Extremist groups develop complex in-group language, also referred to as cryptolects, to exclude or mislead outsiders. We investigate the ability of current language technologies to detect and interpret the cryptolects of two online extremist platforms. Evaluating eight models across six tasks, our results indicate that general purpose LLMs cannot consistently detect or decode extremist language. However, performance can be significantly improved by domain adaptation and specialised prompting techniques. These results provide important insights to inform the development and deployment of automated moderation technologies. We further develop and release novel labelled and unlabelled datasets, including 19.4M posts from extremist platforms and lexicons validated by human experts.

The Only Way is Ethics: A Guide to Ethical Research with Large Language Models

Dec 20, 2024

Abstract:There is a significant body of work looking at the ethical considerations of large language models (LLMs): critiquing tools to measure performance and harms; proposing toolkits to aid in ideation; discussing the risks to workers; considering legislation around privacy and security etc. As yet there is no work that integrates these resources into a single practical guide that focuses on LLMs; we attempt this ambitious goal. We introduce 'LLM Ethics Whitepaper', which we provide as an open and living resource for NLP practitioners, and those tasked with evaluating the ethical implications of others' work. Our goal is to translate ethics literature into concrete recommendations and provocations for thinking with clear first steps, aimed at computer scientists. 'LLM Ethics Whitepaper' distils a thorough literature review into clear Do's and Don'ts, which we present also in this paper. We likewise identify useful toolkits to support ethical work. We refer the interested reader to the full LLM Ethics Whitepaper, which provides a succinct discussion of ethical considerations at each stage in a project lifecycle, as well as citations for the hundreds of papers from which we drew our recommendations. The present paper can be thought of as a pocket guide to conducting ethical research with LLMs.

A Capabilities Approach to Studying Bias and Harm in Language Technologies

Nov 06, 2024Abstract:Mainstream Natural Language Processing (NLP) research has ignored the majority of the world's languages. In moving from excluding the majority of the world's languages to blindly adopting what we make for English, we first risk importing the same harms we have at best mitigated and at least measured for English. However, in evaluating and mitigating harms arising from adopting new technologies into such contexts, we often disregard (1) the actual community needs of Language Technologies, and (2) biases and fairness issues within the context of the communities. In this extended abstract, we consider fairness, bias, and inclusion in Language Technologies through the lens of the Capabilities Approach. The Capabilities Approach centers on what people are capable of achieving, given their intersectional social, political, and economic contexts instead of what resources are (theoretically) available to them. We detail the Capabilities Approach, its relationship to multilingual and multicultural evaluation, and how the framework affords meaningful collaboration with community members in defining and measuring the harms of Language Technologies.

Understanding "Democratization" in NLP and ML Research

Jun 17, 2024

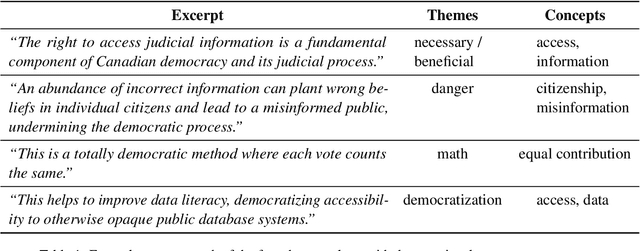

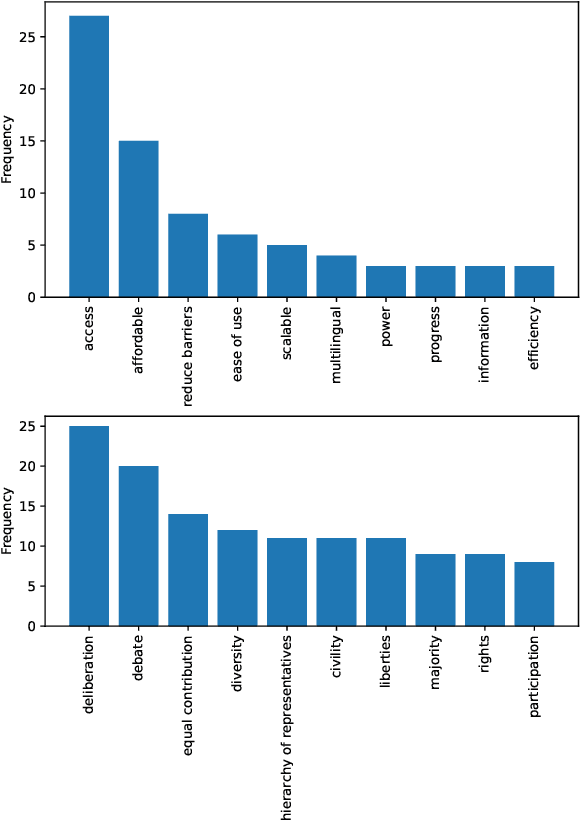

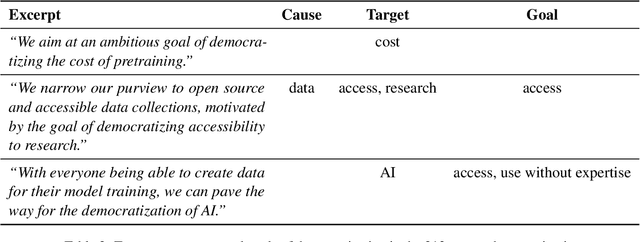

Abstract:Recent improvements in natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning (ML) and increased mainstream adoption have led to researchers frequently discussing the "democratization" of artificial intelligence. In this paper, we seek to clarify how democratization is understood in NLP and ML publications, through large-scale mixed-methods analyses of papers using the keyword "democra*" published in NLP and adjacent venues. We find that democratization is most frequently used to convey (ease of) access to or use of technologies, without meaningfully engaging with theories of democratization, while research using other invocations of "democra*" tends to be grounded in theories of deliberation and debate. Based on our findings, we call for researchers to enrich their use of the term democratization with appropriate theory, towards democratic technologies beyond superficial access.

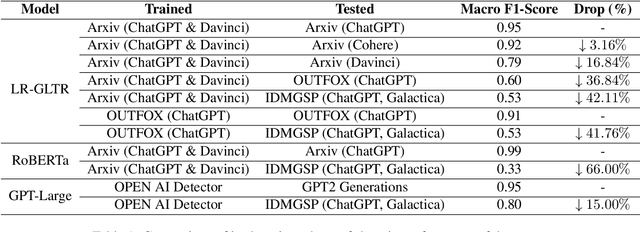

Exploring the Limitations of Detecting Machine-Generated Text

Jun 16, 2024

Abstract:Recent improvements in the quality of the generations by large language models have spurred research into identifying machine-generated text. Systems proposed for the task often achieve high performance. However, humans and machines can produce text in different styles and in different domains, and it remains unclear whether machine generated-text detection models favour particular styles or domains. In this paper, we critically examine the classification performance for detecting machine-generated text by evaluating on texts with varying writing styles. We find that classifiers are highly sensitive to stylistic changes and differences in text complexity, and in some cases degrade entirely to random classifiers. We further find that detection systems are particularly susceptible to misclassify easy-to-read texts while they have high performance for complex texts.

The Perspectivist Paradigm Shift: Assumptions and Challenges of Capturing Human Labels

May 09, 2024Abstract:Longstanding data labeling practices in machine learning involve collecting and aggregating labels from multiple annotators. But what should we do when annotators disagree? Though annotator disagreement has long been seen as a problem to minimize, new perspectivist approaches challenge this assumption by treating disagreement as a valuable source of information. In this position paper, we examine practices and assumptions surrounding the causes of disagreement--some challenged by perspectivist approaches, and some that remain to be addressed--as well as practical and normative challenges for work operating under these assumptions. We conclude with recommendations for the data labeling pipeline and avenues for future research engaging with subjectivity and disagreement.

Classist Tools: Social Class Correlates with Performance in NLP

Mar 07, 2024

Abstract:Since the foundational work of William Labov on the social stratification of language (Labov, 1964), linguistics has made concentrated efforts to explore the links between sociodemographic characteristics and language production and perception. But while there is strong evidence for socio-demographic characteristics in language, they are infrequently used in Natural Language Processing (NLP). Age and gender are somewhat well represented, but Labov's original target, socioeconomic status, is noticeably absent. And yet it matters. We show empirically that NLP disadvantages less-privileged socioeconomic groups. We annotate a corpus of 95K utterances from movies with social class, ethnicity and geographical language variety and measure the performance of NLP systems on three tasks: language modelling, automatic speech recognition, and grammar error correction. We find significant performance disparities that can be attributed to socioeconomic status as well as ethnicity and geographical differences. With NLP technologies becoming ever more ubiquitous and quotidian, they must accommodate all language varieties to avoid disadvantaging already marginalised groups. We argue for the inclusion of socioeconomic class in future language technologies.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge