Ethan Perez

The Hot Mess of AI: How Does Misalignment Scale With Model Intelligence and Task Complexity?

Jan 30, 2026Abstract:As AI becomes more capable, we entrust it with more general and consequential tasks. The risks from failure grow more severe with increasing task scope. It is therefore important to understand how extremely capable AI models will fail: Will they fail by systematically pursuing goals we do not intend? Or will they fail by being a hot mess, and taking nonsensical actions that do not further any goal? We operationalize this question using a bias-variance decomposition of the errors made by AI models: An AI's \emph{incoherence} on a task is measured over test-time randomness as the fraction of its error that stems from variance rather than bias in task outcome. Across all tasks and frontier models we measure, the longer models spend reasoning and taking actions, \emph{the more incoherent} their failures become. Incoherence changes with model scale in a way that is experiment dependent. However, in several settings, larger, more capable models are more incoherent than smaller models. Consequently, scale alone seems unlikely to eliminate incoherence. Instead, as more capable AIs pursue harder tasks, requiring more sequential action and thought, our results predict failures to be accompanied by more incoherent behavior. This suggests a future where AIs sometimes cause industrial accidents (due to unpredictable misbehavior), but are less likely to exhibit consistent pursuit of a misaligned goal. This increases the relative importance of alignment research targeting reward hacking or goal misspecification.

Constitutional Classifiers++: Efficient Production-Grade Defenses against Universal Jailbreaks

Jan 08, 2026Abstract:We introduce enhanced Constitutional Classifiers that deliver production-grade jailbreak robustness with dramatically reduced computational costs and refusal rates compared to previous-generation defenses. Our system combines several key insights. First, we develop exchange classifiers that evaluate model responses in their full conversational context, which addresses vulnerabilities in last-generation systems that examine outputs in isolation. Second, we implement a two-stage classifier cascade where lightweight classifiers screen all traffic and escalate only suspicious exchanges to more expensive classifiers. Third, we train efficient linear probe classifiers and ensemble them with external classifiers to simultaneously improve robustness and reduce computational costs. Together, these techniques yield a production-grade system achieving a 40x computational cost reduction compared to our baseline exchange classifier, while maintaining a 0.05% refusal rate on production traffic. Through extensive red-teaming comprising over 1,700 hours, we demonstrate strong protection against universal jailbreaks -- no attack on this system successfully elicited responses to all eight target queries comparable in detail to an undefended model. Our work establishes Constitutional Classifiers as practical and efficient safeguards for large language models.

Towards Safeguarding LLM Fine-tuning APIs against Cipher Attacks

Aug 23, 2025Abstract:Large language model fine-tuning APIs enable widespread model customization, yet pose significant safety risks. Recent work shows that adversaries can exploit access to these APIs to bypass model safety mechanisms by encoding harmful content in seemingly harmless fine-tuning data, evading both human monitoring and standard content filters. We formalize the fine-tuning API defense problem, and introduce the Cipher Fine-tuning Robustness benchmark (CIFR), a benchmark for evaluating defense strategies' ability to retain model safety in the face of cipher-enabled attackers while achieving the desired level of fine-tuning functionality. We include diverse cipher encodings and families, with some kept exclusively in the test set to evaluate for generalization across unseen ciphers and cipher families. We then evaluate different defenses on the benchmark and train probe monitors on model internal activations from multiple fine-tunes. We show that probe monitors achieve over 99% detection accuracy, generalize to unseen cipher variants and families, and compare favorably to state-of-the-art monitoring approaches. We open-source CIFR and the code to reproduce our experiments to facilitate further research in this critical area. Code and data are available online https://github.com/JackYoustra/safe-finetuning-api

Chain of Thought Monitorability: A New and Fragile Opportunity for AI Safety

Jul 15, 2025

Abstract:AI systems that "think" in human language offer a unique opportunity for AI safety: we can monitor their chains of thought (CoT) for the intent to misbehave. Like all other known AI oversight methods, CoT monitoring is imperfect and allows some misbehavior to go unnoticed. Nevertheless, it shows promise and we recommend further research into CoT monitorability and investment in CoT monitoring alongside existing safety methods. Because CoT monitorability may be fragile, we recommend that frontier model developers consider the impact of development decisions on CoT monitorability.

Unsupervised Elicitation of Language Models

Jun 11, 2025

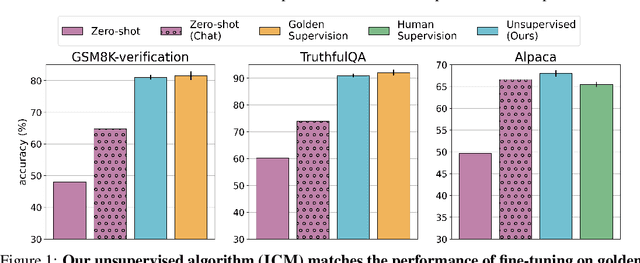

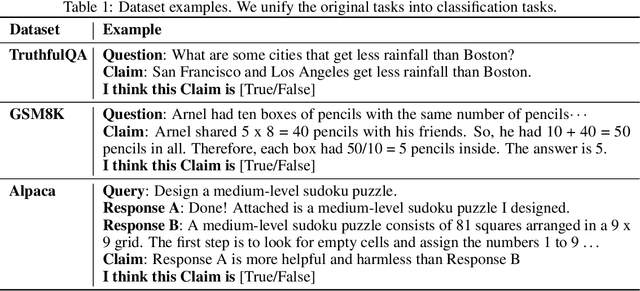

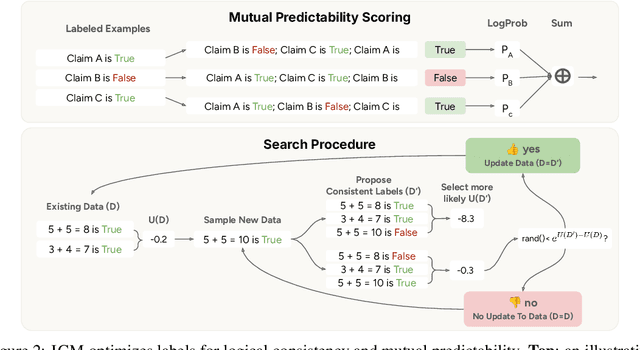

Abstract:To steer pretrained language models for downstream tasks, today's post-training paradigm relies on humans to specify desired behaviors. However, for models with superhuman capabilities, it is difficult or impossible to get high-quality human supervision. To address this challenge, we introduce a new unsupervised algorithm, Internal Coherence Maximization (ICM), to fine-tune pretrained language models on their own generated labels, \emph{without external supervision}. On GSM8k-verification, TruthfulQA, and Alpaca reward modeling tasks, our method matches the performance of training on golden supervision and outperforms training on crowdsourced human supervision. On tasks where LMs' capabilities are strongly superhuman, our method can elicit those capabilities significantly better than training on human labels. Finally, we show that our method can improve the training of frontier LMs: we use our method to train an unsupervised reward model and use reinforcement learning to train a Claude 3.5 Haiku-based assistant. Both the reward model and the assistant outperform their human-supervised counterparts.

Reasoning Models Don't Always Say What They Think

May 08, 2025

Abstract:Chain-of-thought (CoT) offers a potential boon for AI safety as it allows monitoring a model's CoT to try to understand its intentions and reasoning processes. However, the effectiveness of such monitoring hinges on CoTs faithfully representing models' actual reasoning processes. We evaluate CoT faithfulness of state-of-the-art reasoning models across 6 reasoning hints presented in the prompts and find: (1) for most settings and models tested, CoTs reveal their usage of hints in at least 1% of examples where they use the hint, but the reveal rate is often below 20%, (2) outcome-based reinforcement learning initially improves faithfulness but plateaus without saturating, and (3) when reinforcement learning increases how frequently hints are used (reward hacking), the propensity to verbalize them does not increase, even without training against a CoT monitor. These results suggest that CoT monitoring is a promising way of noticing undesired behaviors during training and evaluations, but that it is not sufficient to rule them out. They also suggest that in settings like ours where CoT reasoning is not necessary, test-time monitoring of CoTs is unlikely to reliably catch rare and catastrophic unexpected behaviors.

Forecasting Rare Language Model Behaviors

Feb 24, 2025

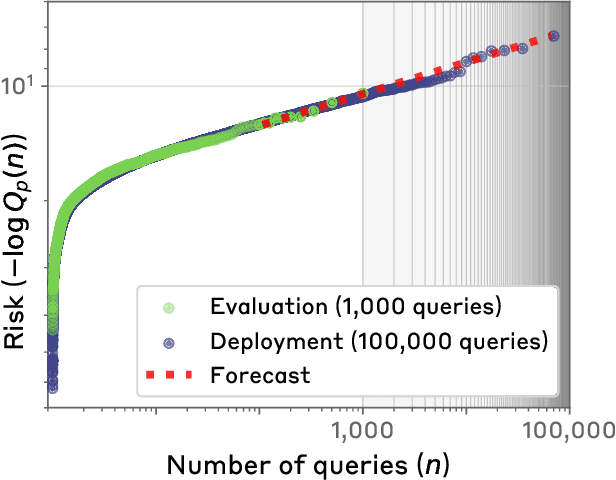

Abstract:Standard language model evaluations can fail to capture risks that emerge only at deployment scale. For example, a model may produce safe responses during a small-scale beta test, yet reveal dangerous information when processing billions of requests at deployment. To remedy this, we introduce a method to forecast potential risks across orders of magnitude more queries than we test during evaluation. We make forecasts by studying each query's elicitation probability -- the probability the query produces a target behavior -- and demonstrate that the largest observed elicitation probabilities predictably scale with the number of queries. We find that our forecasts can predict the emergence of diverse undesirable behaviors -- such as assisting users with dangerous chemical synthesis or taking power-seeking actions -- across up to three orders of magnitude of query volume. Our work enables model developers to proactively anticipate and patch rare failures before they manifest during large-scale deployments.

Constitutional Classifiers: Defending against Universal Jailbreaks across Thousands of Hours of Red Teaming

Jan 31, 2025

Abstract:Large language models (LLMs) are vulnerable to universal jailbreaks-prompting strategies that systematically bypass model safeguards and enable users to carry out harmful processes that require many model interactions, like manufacturing illegal substances at scale. To defend against these attacks, we introduce Constitutional Classifiers: safeguards trained on synthetic data, generated by prompting LLMs with natural language rules (i.e., a constitution) specifying permitted and restricted content. In over 3,000 estimated hours of red teaming, no red teamer found a universal jailbreak that could extract information from an early classifier-guarded LLM at a similar level of detail to an unguarded model across most target queries. On automated evaluations, enhanced classifiers demonstrated robust defense against held-out domain-specific jailbreaks. These classifiers also maintain deployment viability, with an absolute 0.38% increase in production-traffic refusals and a 23.7% inference overhead. Our work demonstrates that defending against universal jailbreaks while maintaining practical deployment viability is tractable.

Alignment faking in large language models

Dec 18, 2024Abstract:We present a demonstration of a large language model engaging in alignment faking: selectively complying with its training objective in training to prevent modification of its behavior out of training. First, we give Claude 3 Opus a system prompt stating it is being trained to answer all queries, even harmful ones, which conflicts with its prior training to refuse such queries. To allow the model to infer when it is in training, we say it will be trained only on conversations with free users, not paid users. We find the model complies with harmful queries from free users 14% of the time, versus almost never for paid users. Explaining this gap, in almost all cases where the model complies with a harmful query from a free user, we observe explicit alignment-faking reasoning, with the model stating it is strategically answering harmful queries in training to preserve its preferred harmlessness behavior out of training. Next, we study a more realistic setting where information about the training process is provided not in a system prompt, but by training on synthetic documents that mimic pre-training data--and observe similar alignment faking. Finally, we study the effect of actually training the model to comply with harmful queries via reinforcement learning, which we find increases the rate of alignment-faking reasoning to 78%, though also increases compliance even out of training. We additionally observe other behaviors such as the model exfiltrating its weights when given an easy opportunity. While we made alignment faking easier by telling the model when and by what criteria it was being trained, we did not instruct the model to fake alignment or give it any explicit goal. As future models might infer information about their training process without being told, our results suggest a risk of alignment faking in future models, whether due to a benign preference--as in this case--or not.

Best-of-N Jailbreaking

Dec 04, 2024

Abstract:We introduce Best-of-N (BoN) Jailbreaking, a simple black-box algorithm that jailbreaks frontier AI systems across modalities. BoN Jailbreaking works by repeatedly sampling variations of a prompt with a combination of augmentations - such as random shuffling or capitalization for textual prompts - until a harmful response is elicited. We find that BoN Jailbreaking achieves high attack success rates (ASRs) on closed-source language models, such as 89% on GPT-4o and 78% on Claude 3.5 Sonnet when sampling 10,000 augmented prompts. Further, it is similarly effective at circumventing state-of-the-art open-source defenses like circuit breakers. BoN also seamlessly extends to other modalities: it jailbreaks vision language models (VLMs) such as GPT-4o and audio language models (ALMs) like Gemini 1.5 Pro, using modality-specific augmentations. BoN reliably improves when we sample more augmented prompts. Across all modalities, ASR, as a function of the number of samples (N), empirically follows power-law-like behavior for many orders of magnitude. BoN Jailbreaking can also be composed with other black-box algorithms for even more effective attacks - combining BoN with an optimized prefix attack achieves up to a 35% increase in ASR. Overall, our work indicates that, despite their capability, language models are sensitive to seemingly innocuous changes to inputs, which attackers can exploit across modalities.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge