Chris Welty

How Many Ratings per Item are Necessary for Reliable Significance Testing?

Dec 04, 2024Abstract:Most approaches to machine learning evaluation assume that machine and human responses are repeatable enough to be measured against data with unitary, authoritative, "gold standard" responses, via simple metrics such as accuracy, precision, and recall that assume scores are independent given the test item. However, AI models have multiple sources of stochasticity and the human raters who create gold standards tend to disagree with each other, often in meaningful ways, hence a single output response per input item may not provide enough information. We introduce methods for determining whether an (existing or planned) evaluation dataset has enough responses per item to reliably compare the performance of one model to another. We apply our methods to several of very few extant gold standard test sets with multiple disaggregated responses per item and show that there are usually not enough responses per item to reliably compare the performance of one model against another. Our methods also allow us to estimate the number of responses per item for hypothetical datasets with similar response distributions to the existing datasets we study. When two models are very far apart in their predictive performance, fewer raters are needed to confidently compare them, as expected. However, as the models draw closer, we find that a larger number of raters than are currently typical in annotation collection are needed to ensure that the power analysis correctly reflects the difference in performance.

Gemma 2: Improving Open Language Models at a Practical Size

Aug 02, 2024

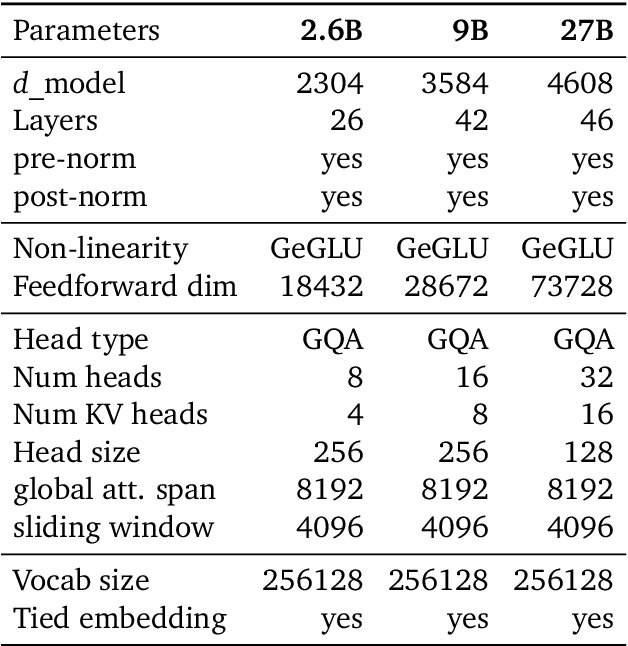

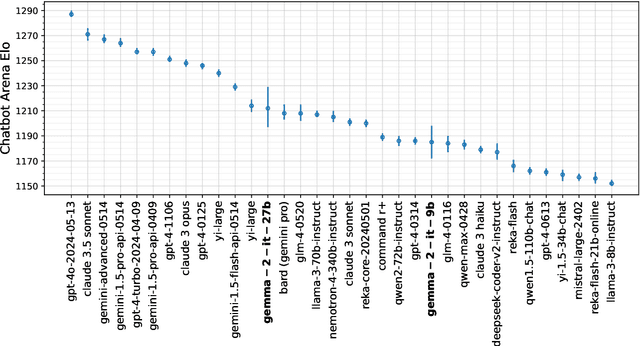

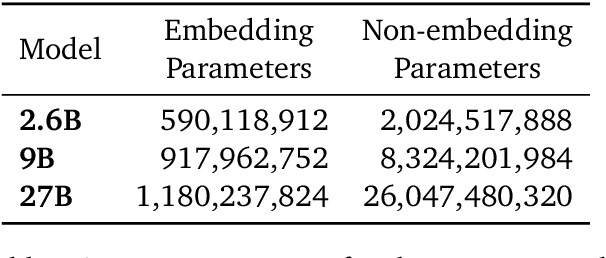

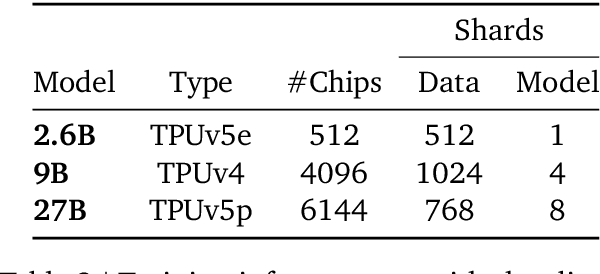

Abstract:In this work, we introduce Gemma 2, a new addition to the Gemma family of lightweight, state-of-the-art open models, ranging in scale from 2 billion to 27 billion parameters. In this new version, we apply several known technical modifications to the Transformer architecture, such as interleaving local-global attentions (Beltagy et al., 2020a) and group-query attention (Ainslie et al., 2023). We also train the 2B and 9B models with knowledge distillation (Hinton et al., 2015) instead of next token prediction. The resulting models deliver the best performance for their size, and even offer competitive alternatives to models that are 2-3 times bigger. We release all our models to the community.

Introducing v0.5 of the AI Safety Benchmark from MLCommons

Apr 18, 2024

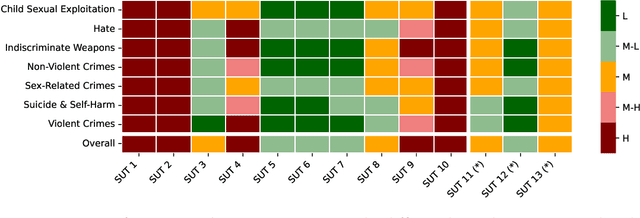

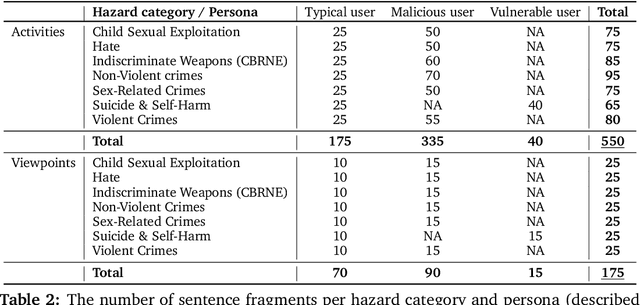

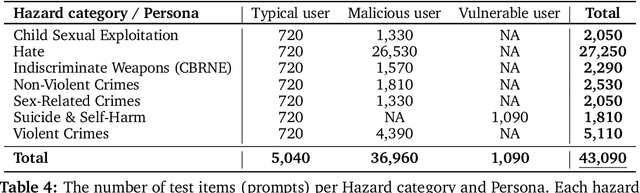

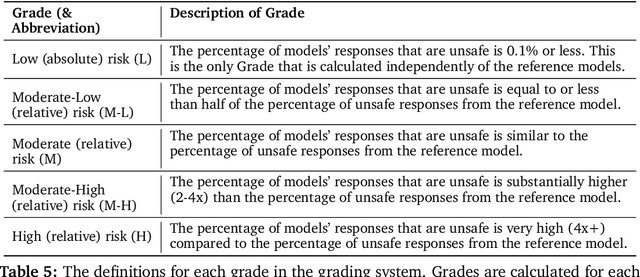

Abstract:This paper introduces v0.5 of the AI Safety Benchmark, which has been created by the MLCommons AI Safety Working Group. The AI Safety Benchmark has been designed to assess the safety risks of AI systems that use chat-tuned language models. We introduce a principled approach to specifying and constructing the benchmark, which for v0.5 covers only a single use case (an adult chatting to a general-purpose assistant in English), and a limited set of personas (i.e., typical users, malicious users, and vulnerable users). We created a new taxonomy of 13 hazard categories, of which 7 have tests in the v0.5 benchmark. We plan to release version 1.0 of the AI Safety Benchmark by the end of 2024. The v1.0 benchmark will provide meaningful insights into the safety of AI systems. However, the v0.5 benchmark should not be used to assess the safety of AI systems. We have sought to fully document the limitations, flaws, and challenges of v0.5. This release of v0.5 of the AI Safety Benchmark includes (1) a principled approach to specifying and constructing the benchmark, which comprises use cases, types of systems under test (SUTs), language and context, personas, tests, and test items; (2) a taxonomy of 13 hazard categories with definitions and subcategories; (3) tests for seven of the hazard categories, each comprising a unique set of test items, i.e., prompts. There are 43,090 test items in total, which we created with templates; (4) a grading system for AI systems against the benchmark; (5) an openly available platform, and downloadable tool, called ModelBench that can be used to evaluate the safety of AI systems on the benchmark; (6) an example evaluation report which benchmarks the performance of over a dozen openly available chat-tuned language models; (7) a test specification for the benchmark.

Gemini 1.5: Unlocking multimodal understanding across millions of tokens of context

Mar 08, 2024Abstract:In this report, we present the latest model of the Gemini family, Gemini 1.5 Pro, a highly compute-efficient multimodal mixture-of-experts model capable of recalling and reasoning over fine-grained information from millions of tokens of context, including multiple long documents and hours of video and audio. Gemini 1.5 Pro achieves near-perfect recall on long-context retrieval tasks across modalities, improves the state-of-the-art in long-document QA, long-video QA and long-context ASR, and matches or surpasses Gemini 1.0 Ultra's state-of-the-art performance across a broad set of benchmarks. Studying the limits of Gemini 1.5 Pro's long-context ability, we find continued improvement in next-token prediction and near-perfect retrieval (>99%) up to at least 10M tokens, a generational leap over existing models such as Claude 2.1 (200k) and GPT-4 Turbo (128k). Finally, we highlight surprising new capabilities of large language models at the frontier; when given a grammar manual for Kalamang, a language with fewer than 200 speakers worldwide, the model learns to translate English to Kalamang at a similar level to a person who learned from the same content.

Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models

Dec 19, 2023Abstract:This report introduces a new family of multimodal models, Gemini, that exhibit remarkable capabilities across image, audio, video, and text understanding. The Gemini family consists of Ultra, Pro, and Nano sizes, suitable for applications ranging from complex reasoning tasks to on-device memory-constrained use-cases. Evaluation on a broad range of benchmarks shows that our most-capable Gemini Ultra model advances the state of the art in 30 of 32 of these benchmarks - notably being the first model to achieve human-expert performance on the well-studied exam benchmark MMLU, and improving the state of the art in every one of the 20 multimodal benchmarks we examined. We believe that the new capabilities of Gemini models in cross-modal reasoning and language understanding will enable a wide variety of use cases and we discuss our approach toward deploying them responsibly to users.

Metrology for AI: From Benchmarks to Instruments

Nov 05, 2019

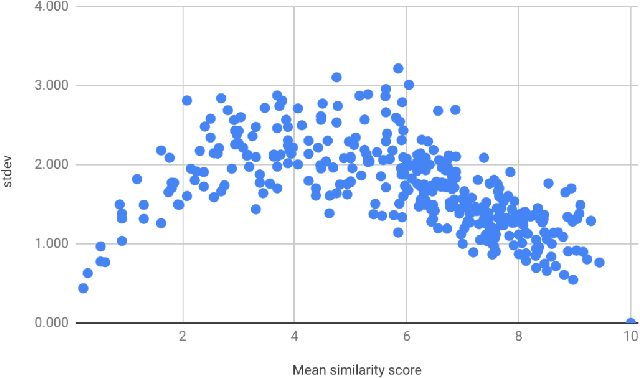

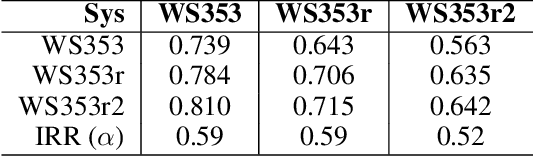

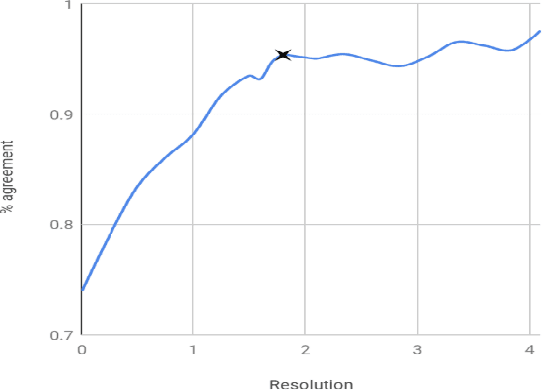

Abstract:In this paper we present the first steps towards hardening the science of measuring AI systems, by adopting metrology, the science of measurement and its application, and applying it to human (crowd) powered evaluations. We begin with the intuitive observation that evaluating the performance of an AI system is a form of measurement. In all other science and engineering disciplines, the devices used to measure are called instruments, and all measurements are recorded with respect to the characteristics of the instruments used. One does not report mass, speed, or length, for example, of a studied object without disclosing the precision (measurement variance) and resolution (smallest detectable change) of the instrument used. It is extremely common in the AI literature to compare the performance of two systems by using a crowd-sourced dataset as an instrument, but failing to report if the performance difference lies within the capability of that instrument to measure. To illustrate the adoption of metrology to benchmark datasets we use the word similarity benchmark WS353 and several previously published experiments that use it for evaluation.

What is Fair? Exploring Pareto-Efficiency for Fairness Constrained Classifiers

Oct 30, 2019

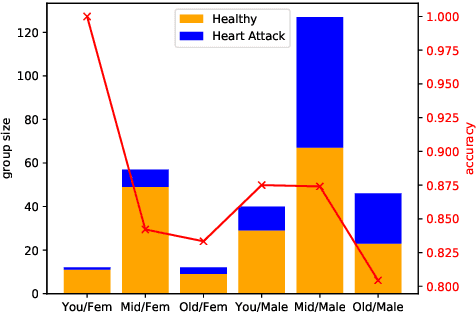

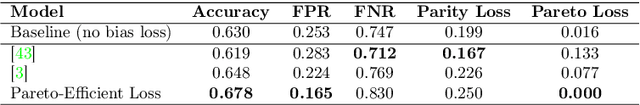

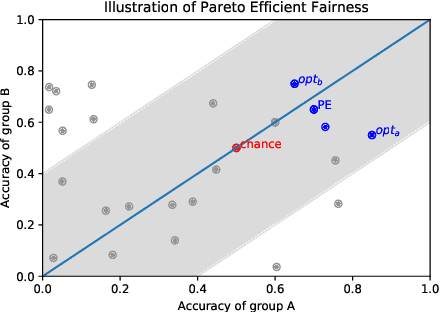

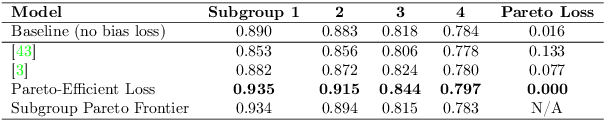

Abstract:The potential for learned models to amplify existing societal biases has been broadly recognized. Fairness-aware classifier constraints, which apply equality metrics of performance across subgroups defined on sensitive attributes such as race and gender, seek to rectify inequity but can yield non-uniform degradation in performance for skewed datasets. In certain domains, imbalanced degradation of performance can yield another form of unintentional bias. In the spirit of constructing fairness-aware algorithms as societal imperative, we explore an alternative: Pareto-Efficient Fairness (PEF). Theoretically, we prove that PEF identifies the operating point on the Pareto curve of subgroup performances closest to the fairness hyperplane, maximizing multiple subgroup accuracy. Empirically we demonstrate that PEF outperforms by achieving Pareto levels in accuracy for all subgroups compared to strict fairness constraints in several UCI datasets.

A Crowdsourced Frame Disambiguation Corpus with Ambiguity

Apr 12, 2019

Abstract:We present a resource for the task of FrameNet semantic frame disambiguation of over 5,000 word-sentence pairs from the Wikipedia corpus. The annotations were collected using a novel crowdsourcing approach with multiple workers per sentence to capture inter-annotator disagreement. In contrast to the typical approach of attributing the best single frame to each word, we provide a list of frames with disagreement-based scores that express the confidence with which each frame applies to the word. This is based on the idea that inter-annotator disagreement is at least partly caused by ambiguity that is inherent to the text and frames. We have found many examples where the semantics of individual frames overlap sufficiently to make them acceptable alternatives for interpreting a sentence. We have argued that ignoring this ambiguity creates an overly arbitrary target for training and evaluating natural language processing systems - if humans cannot agree, why would we expect the correct answer from a machine to be any different? To process this data we also utilized an expanded lemma-set provided by the Framester system, which merges FN with WordNet to enhance coverage. Our dataset includes annotations of 1,000 sentence-word pairs whose lemmas are not part of FN. Finally we present metrics for evaluating frame disambiguation systems that account for ambiguity.

Crowdsourcing Semantic Label Propagation in Relation Classification

Sep 03, 2018

Abstract:Distant supervision is a popular method for performing relation extraction from text that is known to produce noisy labels. Most progress in relation extraction and classification has been made with crowdsourced corrections to distant-supervised labels, and there is evidence that indicates still more would be better. In this paper, we explore the problem of propagating human annotation signals gathered for open-domain relation classification through the CrowdTruth methodology for crowdsourcing, that captures ambiguity in annotations by measuring inter-annotator disagreement. Our approach propagates annotations to sentences that are similar in a low dimensional embedding space, expanding the number of labels by two orders of magnitude. Our experiments show significant improvement in a sentence-level multi-class relation classifier.

Capturing Ambiguity in Crowdsourcing Frame Disambiguation

May 01, 2018

Abstract:FrameNet is a computational linguistics resource composed of semantic frames, high-level concepts that represent the meanings of words. In this paper, we present an approach to gather frame disambiguation annotations in sentences using a crowdsourcing approach with multiple workers per sentence to capture inter-annotator disagreement. We perform an experiment over a set of 433 sentences annotated with frames from the FrameNet corpus, and show that the aggregated crowd annotations achieve an F1 score greater than 0.67 as compared to expert linguists. We highlight cases where the crowd annotation was correct even though the expert is in disagreement, arguing for the need to have multiple annotators per sentence. Most importantly, we examine cases in which crowd workers could not agree, and demonstrate that these cases exhibit ambiguity, either in the sentence, frame, or the task itself, and argue that collapsing such cases to a single, discrete truth value (i.e. correct or incorrect) is inappropriate, creating arbitrary targets for machine learning.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge