Steve Yadlowsky

OpenAI GPT-5 System Card

Dec 19, 2025Abstract:This is the system card published alongside the OpenAI GPT-5 launch, August 2025. GPT-5 is a unified system with a smart and fast model that answers most questions, a deeper reasoning model for harder problems, and a real-time router that quickly decides which model to use based on conversation type, complexity, tool needs, and explicit intent (for example, if you say 'think hard about this' in the prompt). The router is continuously trained on real signals, including when users switch models, preference rates for responses, and measured correctness, improving over time. Once usage limits are reached, a mini version of each model handles remaining queries. This system card focuses primarily on gpt-5-thinking and gpt-5-main, while evaluations for other models are available in the appendix. The GPT-5 system not only outperforms previous models on benchmarks and answers questions more quickly, but -- more importantly -- is more useful for real-world queries. We've made significant advances in reducing hallucinations, improving instruction following, and minimizing sycophancy, and have leveled up GPT-5's performance in three of ChatGPT's most common uses: writing, coding, and health. All of the GPT-5 models additionally feature safe-completions, our latest approach to safety training to prevent disallowed content. Similarly to ChatGPT agent, we have decided to treat gpt-5-thinking as High capability in the Biological and Chemical domain under our Preparedness Framework, activating the associated safeguards. While we do not have definitive evidence that this model could meaningfully help a novice to create severe biological harm -- our defined threshold for High capability -- we have chosen to take a precautionary approach.

LearnLM: Improving Gemini for Learning

Dec 21, 2024

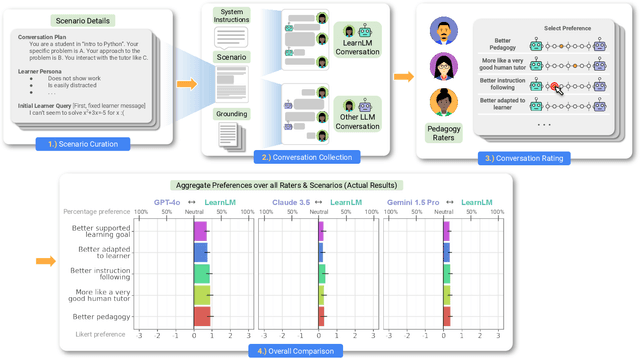

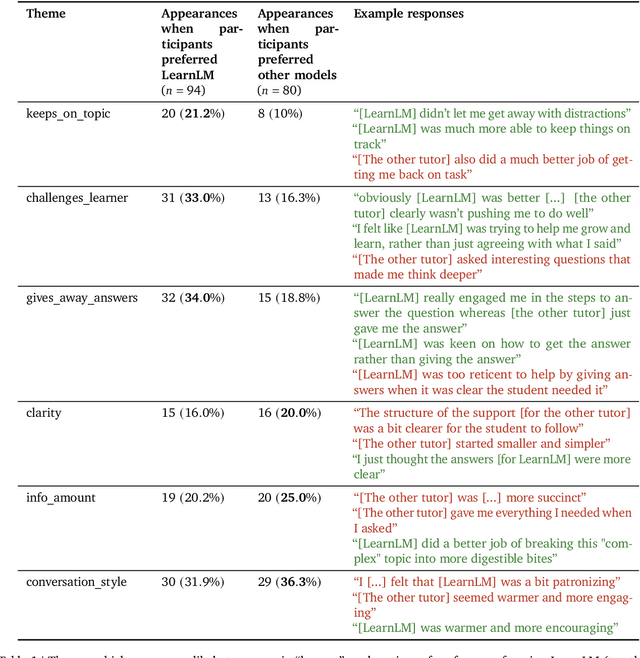

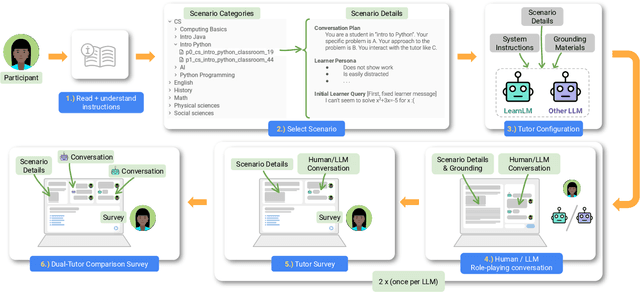

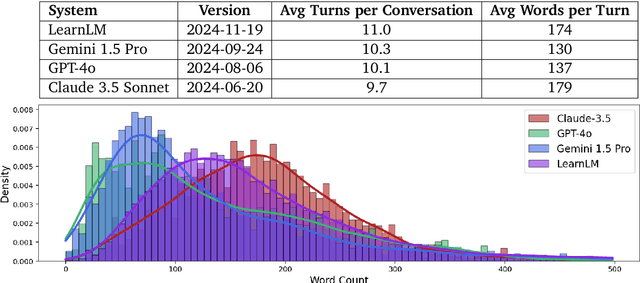

Abstract:Today's generative AI systems are tuned to present information by default rather than engage users in service of learning as a human tutor would. To address the wide range of potential education use cases for these systems, we reframe the challenge of injecting pedagogical behavior as one of \textit{pedagogical instruction following}, where training and evaluation examples include system-level instructions describing the specific pedagogy attributes present or desired in subsequent model turns. This framing avoids committing our models to any particular definition of pedagogy, and instead allows teachers or developers to specify desired model behavior. It also clears a path to improving Gemini models for learning -- by enabling the addition of our pedagogical data to post-training mixtures -- alongside their rapidly expanding set of capabilities. Both represent important changes from our initial tech report. We show how training with pedagogical instruction following produces a LearnLM model (available on Google AI Studio) that is preferred substantially by expert raters across a diverse set of learning scenarios, with average preference strengths of 31\% over GPT-4o, 11\% over Claude 3.5, and 13\% over the Gemini 1.5 Pro model LearnLM was based on.

Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models

Dec 19, 2023Abstract:This report introduces a new family of multimodal models, Gemini, that exhibit remarkable capabilities across image, audio, video, and text understanding. The Gemini family consists of Ultra, Pro, and Nano sizes, suitable for applications ranging from complex reasoning tasks to on-device memory-constrained use-cases. Evaluation on a broad range of benchmarks shows that our most-capable Gemini Ultra model advances the state of the art in 30 of 32 of these benchmarks - notably being the first model to achieve human-expert performance on the well-studied exam benchmark MMLU, and improving the state of the art in every one of the 20 multimodal benchmarks we examined. We believe that the new capabilities of Gemini models in cross-modal reasoning and language understanding will enable a wide variety of use cases and we discuss our approach toward deploying them responsibly to users.

Pretraining Data Mixtures Enable Narrow Model Selection Capabilities in Transformer Models

Nov 01, 2023

Abstract:Transformer models, notably large language models (LLMs), have the remarkable ability to perform in-context learning (ICL) -- to perform new tasks when prompted with unseen input-output examples without any explicit model training. In this work, we study how effectively transformers can bridge between their pretraining data mixture, comprised of multiple distinct task families, to identify and learn new tasks in-context which are both inside and outside the pretraining distribution. Building on previous work, we investigate this question in a controlled setting, where we study transformer models trained on sequences of $(x, f(x))$ pairs rather than natural language. Our empirical results show transformers demonstrate near-optimal unsupervised model selection capabilities, in their ability to first in-context identify different task families and in-context learn within them when the task families are well-represented in their pretraining data. However when presented with tasks or functions which are out-of-domain of their pretraining data, we demonstrate various failure modes of transformers and degradation of their generalization for even simple extrapolation tasks. Together our results highlight that the impressive ICL abilities of high-capacity sequence models may be more closely tied to the coverage of their pretraining data mixtures than inductive biases that create fundamental generalization capabilities.

Choosing a Proxy Metric from Past Experiments

Sep 14, 2023

Abstract:In many randomized experiments, the treatment effect of the long-term metric (i.e. the primary outcome of interest) is often difficult or infeasible to measure. Such long-term metrics are often slow to react to changes and sufficiently noisy they are challenging to faithfully estimate in short-horizon experiments. A common alternative is to measure several short-term proxy metrics in the hope they closely track the long-term metric -- so they can be used to effectively guide decision-making in the near-term. We introduce a new statistical framework to both define and construct an optimal proxy metric for use in a homogeneous population of randomized experiments. Our procedure first reduces the construction of an optimal proxy metric in a given experiment to a portfolio optimization problem which depends on the true latent treatment effects and noise level of experiment under consideration. We then denoise the observed treatment effects of the long-term metric and a set of proxies in a historical corpus of randomized experiments to extract estimates of the latent treatment effects for use in the optimization problem. One key insight derived from our approach is that the optimal proxy metric for a given experiment is not apriori fixed; rather it should depend on the sample size (or effective noise level) of the randomized experiment for which it is deployed. To instantiate and evaluate our framework, we employ our methodology in a large corpus of randomized experiments from an industrial recommendation system and construct proxy metrics that perform favorably relative to several baselines.

Diagnosing Model Performance Under Distribution Shift

Mar 10, 2023Abstract:Prediction models can perform poorly when deployed to target distributions different from the training distribution. To understand these operational failure modes, we develop a method, called DIstribution Shift DEcomposition (DISDE), to attribute a drop in performance to different types of distribution shifts. Our approach decomposes the performance drop into terms for 1) an increase in harder but frequently seen examples from training, 2) changes in the relationship between features and outcomes, and 3) poor performance on examples infrequent or unseen during training. These terms are defined by fixing a distribution on $X$ while varying the conditional distribution of $Y \mid X$ between training and target, or by fixing the conditional distribution of $Y \mid X$ while varying the distribution on $X$. In order to do this, we define a hypothetical distribution on $X$ consisting of values common in both training and target, over which it is easy to compare $Y \mid X$ and thus predictive performance. We estimate performance on this hypothetical distribution via reweighting methods. Empirically, we show how our method can 1) inform potential modeling improvements across distribution shifts for employment prediction on tabular census data, and 2) help to explain why certain domain adaptation methods fail to improve model performance for satellite image classification.

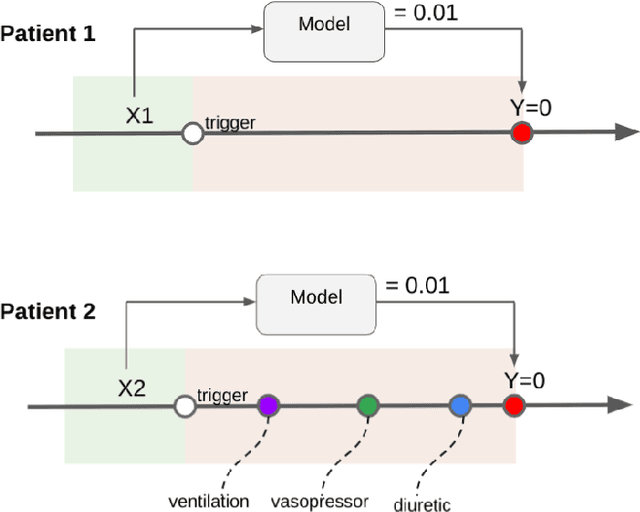

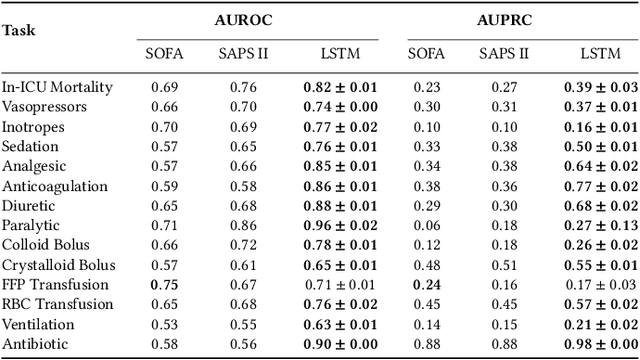

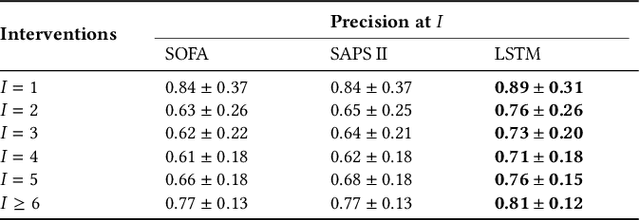

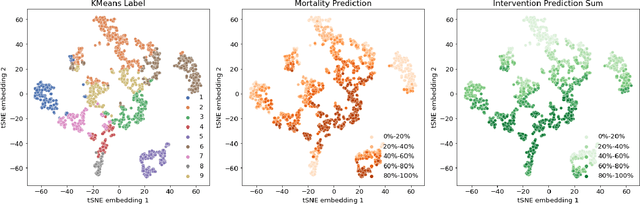

Boosting the interpretability of clinical risk scores with intervention predictions

Jul 06, 2022

Abstract:Machine learning systems show significant promise for forecasting patient adverse events via risk scores. However, these risk scores implicitly encode assumptions about future interventions that the patient is likely to receive, based on the intervention policy present in the training data. Without this important context, predictions from such systems are less interpretable for clinicians. We propose a joint model of intervention policy and adverse event risk as a means to explicitly communicate the model's assumptions about future interventions. We develop such an intervention policy model on MIMIC-III, a real world de-identified ICU dataset, and discuss some use cases that highlight the utility of this approach. We show how combining typical risk scores, such as the likelihood of mortality, with future intervention probability scores leads to more interpretable clinical predictions.

Calibration Error for Heterogeneous Treatment Effects

Mar 24, 2022

Abstract:Recently, many researchers have advanced data-driven methods for modeling heterogeneous treatment effects (HTEs). Even still, estimation of HTEs is a difficult task -- these methods frequently over- or under-estimate the treatment effects, leading to poor calibration of the resulting models. However, while many methods exist for evaluating the calibration of prediction and classification models, formal approaches to assess the calibration of HTE models are limited to the calibration slope. In this paper, we define an analogue of the \smash{($\ell_2$)} expected calibration error for HTEs, and propose a robust estimator. Our approach is motivated by doubly robust treatment effect estimators, making it unbiased, and resilient to confounding, overfitting, and high-dimensionality issues. Furthermore, our method is straightforward to adapt to many structures under which treatment effects can be identified, including randomized trials, observational studies, and survival analysis. We illustrate how to use our proposed metric to evaluate the calibration of learned HTE models through the application to the CRITEO-UPLIFT Trial.

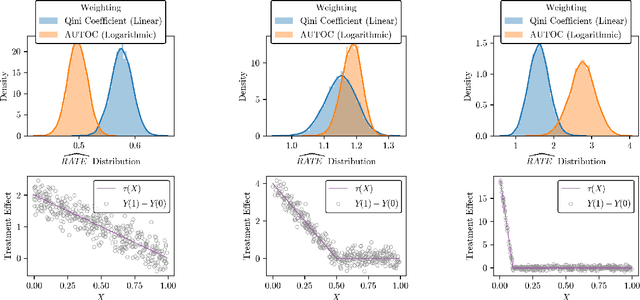

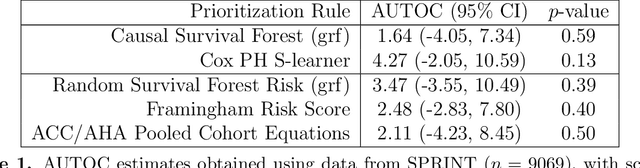

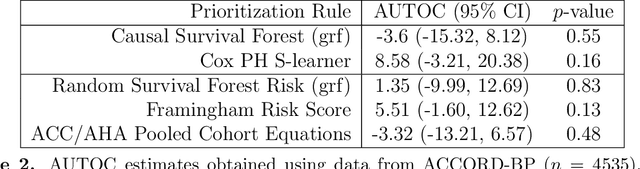

Evaluating Treatment Prioritization Rules via Rank-Weighted Average Treatment Effects

Nov 15, 2021

Abstract:There are a number of available methods that can be used for choosing whom to prioritize treatment, including ones based on treatment effect estimation, risk scoring, and hand-crafted rules. We propose rank-weighted average treatment effect (RATE) metrics as a simple and general family of metrics for comparing treatment prioritization rules on a level playing field. RATEs are agnostic as to how the prioritization rules were derived, and only assesses them based on how well they succeed in identifying units that benefit the most from treatment. We define a family of RATE estimators and prove a central limit theorem that enables asymptotically exact inference in a wide variety of randomized and observational study settings. We provide justification for the use of bootstrapped confidence intervals and a framework for testing hypotheses about heterogeneity in treatment effectiveness correlated with the prioritization rule. Our definition of the RATE nests a number of existing metrics, including the Qini coefficient, and our analysis directly yields inference methods for these metrics. We demonstrate our approach in examples drawn from both personalized medicine and marketing. In the medical setting, using data from the SPRINT and ACCORD-BP randomized control trials, we find no significant evidence of heterogeneous treatment effects. On the other hand, in a large marketing trial, we find robust evidence of heterogeneity in the treatment effects of some digital advertising campaigns and demonstrate how RATEs can be used to compare targeting rules that prioritize estimated risk vs. those that prioritize estimated treatment benefit.

The MultiBERTs: BERT Reproductions for Robustness Analysis

Jun 30, 2021

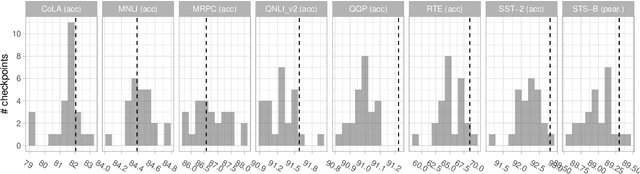

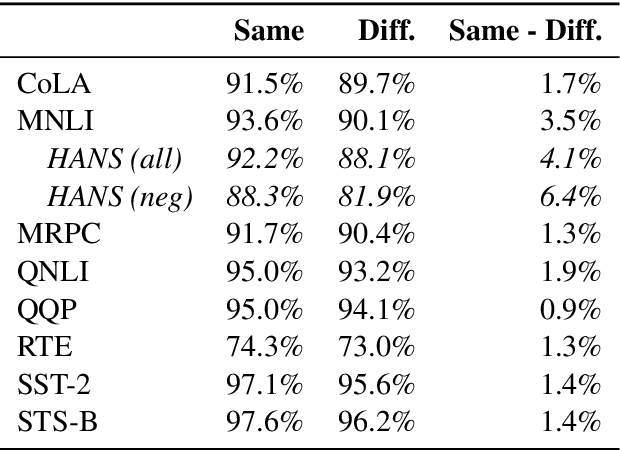

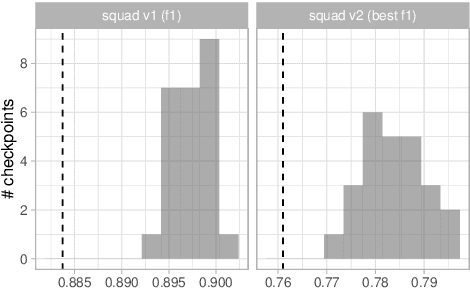

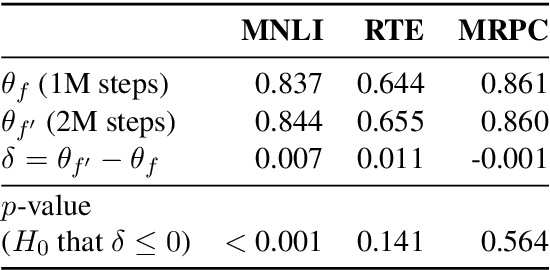

Abstract:Experiments with pretrained models such as BERT are often based on a single checkpoint. While the conclusions drawn apply to the artifact (i.e., the particular instance of the model), it is not always clear whether they hold for the more general procedure (which includes the model architecture, training data, initialization scheme, and loss function). Recent work has shown that re-running pretraining can lead to substantially different conclusions about performance, suggesting that alternative evaluations are needed to make principled statements about procedures. To address this question, we introduce MultiBERTs: a set of 25 BERT-base checkpoints, trained with similar hyper-parameters as the original BERT model but differing in random initialization and data shuffling. The aim is to enable researchers to draw robust and statistically justified conclusions about pretraining procedures. The full release includes 25 fully trained checkpoints, as well as statistical guidelines and a code library implementing our recommended hypothesis testing methods. Finally, for five of these models we release a set of 28 intermediate checkpoints in order to support research on learning dynamics.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge