Siddhartha Sen

When does predictive inverse dynamics outperform behavior cloning?

Jan 29, 2026Abstract:Behavior cloning (BC) is a practical offline imitation learning method, but it often fails when expert demonstrations are limited. Recent works have introduced a class of architectures named predictive inverse dynamics models (PIDM) that combine a future state predictor with an inverse dynamics model (IDM). While PIDM often outperforms BC, the reasons behind its benefits remain unclear. In this paper, we provide a theoretical explanation: PIDM introduces a bias-variance tradeoff. While predicting the future state introduces bias, conditioning the IDM on the prediction can significantly reduce variance. We establish conditions on the state predictor bias for PIDM to achieve lower prediction error and higher sample efficiency than BC, with the gap widening when additional data sources are available. We validate the theoretical insights empirically in 2D navigation tasks, where BC requires up to five times (three times on average) more demonstrations than PIDM to reach comparable performance; and in a complex 3D environment in a modern video game with high-dimensional visual inputs and stochastic transitions, where BC requires over 66\% more samples than PIDM.

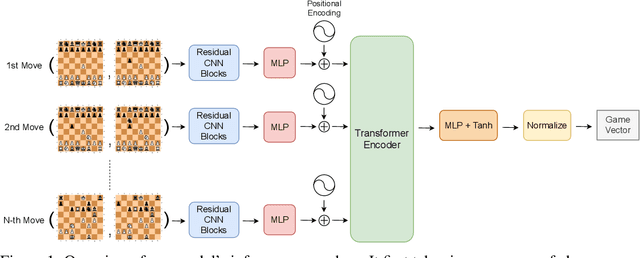

Generative Modeling of Individual Behavior at Scale

Feb 20, 2025Abstract:There has been a growing interest in using AI to model human behavior, particularly in domains where humans interact with this technology. While most existing work models human behavior at an aggregate level, our goal is to model behavior at the individual level. Recent approaches to behavioral stylometry -- or the task of identifying a person from their actions alone -- have shown promise in domains like chess, but these approaches are either not scalable (e.g., fine-tune a separate model for each person) or not generative, in that they cannot generate actions. We address these limitations by framing behavioral stylometry as a multi-task learning problem -- where each task represents a distinct person -- and use parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods to learn an explicit style vector for each person. Style vectors are generative: they selectively activate shared "skill" parameters to generate actions in the style of each person. They also induce a latent space that we can interpret and manipulate algorithmically. In particular, we develop a general technique for style steering that allows us to steer a player's style vector towards a desired property. We apply our approach to two very different games, at unprecedented scales: chess (47,864 players) and Rocket League (2,000 players). We also show generality beyond gaming by applying our method to image generation, where we learn style vectors for 10,177 celebrities and use these vectors to steer their images.

Progressive Safeguards for Safe and Model-Agnostic Reinforcement Learning

Oct 31, 2024Abstract:In this paper we propose a formal, model-agnostic meta-learning framework for safe reinforcement learning. Our framework is inspired by how parents safeguard their children across a progression of increasingly riskier tasks, imparting a sense of safety that is carried over from task to task. We model this as a meta-learning process where each task is synchronized with a safeguard that monitors safety and provides a reward signal to the agent. The safeguard is implemented as a finite-state machine based on a safety specification; the reward signal is formally shaped around this specification. The safety specification and its corresponding safeguard can be arbitrarily complex and non-Markovian, which adds flexibility to the training process and explainability to the learned policy. The design of the safeguard is manual but it is high-level and model-agnostic, which gives rise to an end-to-end safe learning approach with wide applicability, from pixel-level game control to language model fine-tuning. Starting from a given set of safety specifications (tasks), we train a model such that it can adapt to new specifications using only a small number of training samples. This is made possible by our method for efficiently transferring safety bias between tasks, which effectively minimizes the number of safety violations. We evaluate our framework in a Minecraft-inspired Gridworld, a VizDoom game environment, and an LLM fine-tuning application. Agents trained with our approach achieve near-minimal safety violations, while baselines are shown to underperform.

Maia-2: A Unified Model for Human-AI Alignment in Chess

Sep 30, 2024

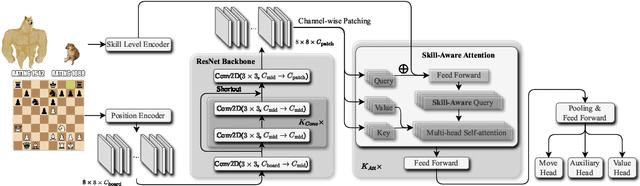

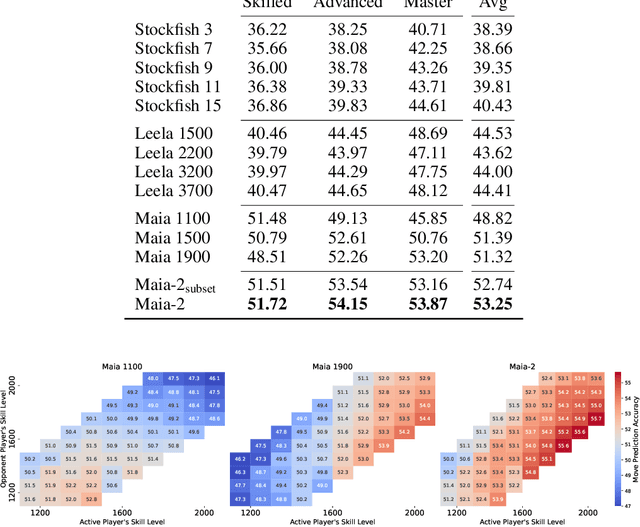

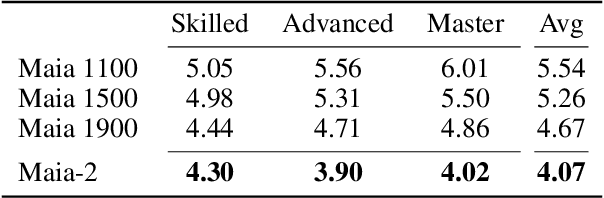

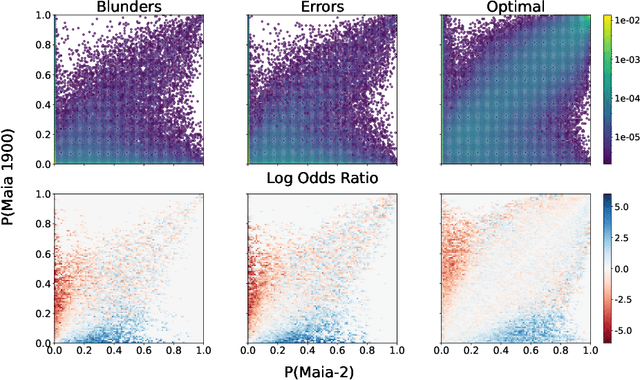

Abstract:There are an increasing number of domains in which artificial intelligence (AI) systems both surpass human ability and accurately model human behavior. This introduces the possibility of algorithmically-informed teaching in these domains through more relatable AI partners and deeper insights into human decision-making. Critical to achieving this goal, however, is coherently modeling human behavior at various skill levels. Chess is an ideal model system for conducting research into this kind of human-AI alignment, with its rich history as a pivotal testbed for AI research, mature superhuman AI systems like AlphaZero, and precise measurements of skill via chess rating systems. Previous work in modeling human decision-making in chess uses completely independent models to capture human style at different skill levels, meaning they lack coherence in their ability to adapt to the full spectrum of human improvement and are ultimately limited in their effectiveness as AI partners and teaching tools. In this work, we propose a unified modeling approach for human-AI alignment in chess that coherently captures human style across different skill levels and directly captures how people improve. Recognizing the complex, non-linear nature of human learning, we introduce a skill-aware attention mechanism to dynamically integrate players' strengths with encoded chess positions, enabling our model to be sensitive to evolving player skill. Our experimental results demonstrate that this unified framework significantly enhances the alignment between AI and human players across a diverse range of expertise levels, paving the way for deeper insights into human decision-making and AI-guided teaching tools.

Designing Skill-Compatible AI: Methodologies and Frameworks in Chess

May 08, 2024

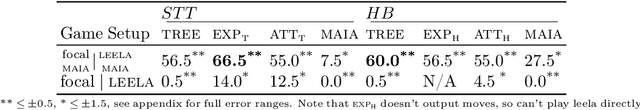

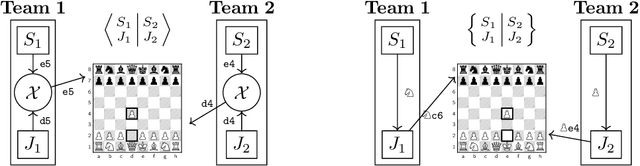

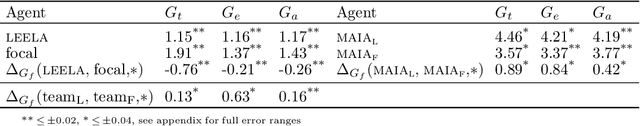

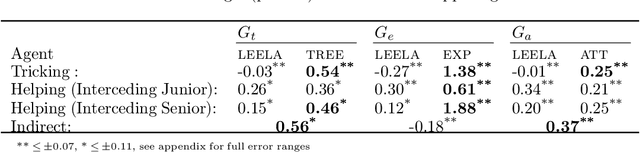

Abstract:Powerful artificial intelligence systems are often used in settings where they must interact with agents that are computationally much weaker, for example when they work alongside humans or operate in complex environments where some tasks are handled by algorithms, heuristics, or other entities of varying computational power. For AI agents to successfully interact in these settings, however, achieving superhuman performance alone is not sufficient; they also need to account for suboptimal actions or idiosyncratic style from their less-skilled counterparts. We propose a formal evaluation framework for assessing the compatibility of near-optimal AI with interaction partners who may have much lower levels of skill; we use popular collaborative chess variants as model systems to study and develop AI agents that can successfully interact with lower-skill entities. Traditional chess engines designed to output near-optimal moves prove to be inadequate partners when paired with engines of various lower skill levels in this domain, as they are not designed to consider the presence of other agents. We contribute three methodologies to explicitly create skill-compatible AI agents in complex decision-making settings, and two chess game frameworks designed to foster collaboration between powerful AI agents and less-skilled partners. On these frameworks, our agents outperform state-of-the-art chess AI (based on AlphaZero) despite being weaker in conventional chess, demonstrating that skill-compatibility is a tangible trait that is qualitatively and measurably distinct from raw performance. Our evaluations further explore and clarify the mechanisms by which our agents achieve skill-compatibility.

Visual Encoders for Data-Efficient Imitation Learning in Modern Video Games

Dec 04, 2023Abstract:Video games have served as useful benchmarks for the decision making community, but going beyond Atari games towards training agents in modern games has been prohibitively expensive for the vast majority of the research community. Recent progress in the research, development and open release of large vision models has the potential to amortize some of these costs across the community. However, it is currently unclear which of these models have learnt representations that retain information critical for sequential decision making. Towards enabling wider participation in the research of gameplaying agents in modern games, we present a systematic study of imitation learning with publicly available visual encoders compared to the typical, task-specific, end-to-end training approach in Minecraft, Minecraft Dungeons and Counter-Strike: Global Offensive.

Variance, Self-Consistency, and Arbitrariness in Fair Classification

Feb 01, 2023Abstract:In fair classification, it is common to train a model, and to compare and correct subgroup-specific error rates for disparities. However, even if a model's classification decisions satisfy a fairness metric, it is not necessarily the case that these decisions are equally confident. This becomes clear if we measure variance: We can fix everything in the learning process except the subset of training data, train multiple models, measure (dis)agreement in predictions for each test example, and interpret disagreement to mean that the learning process is more unstable with respect to its classification decision. Empirically, some decisions can in fact be so unstable that they are effectively arbitrary. To reduce this arbitrariness, we formalize a notion of self-consistency of a learning process, develop an ensembling algorithm that provably increases self-consistency, and empirically demonstrate its utility to often improve both fairness and accuracy. Further, our evaluation reveals a startling observation: Applying ensembling to common fair classification benchmarks can significantly reduce subgroup error rate disparities, without employing common pre-, in-, or post-processing fairness interventions. Taken together, our results indicate that variance, particularly on small datasets, can muddle the reliability of conclusions about fairness. One solution is to develop larger benchmark tasks. To this end, we release a toolkit that makes the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act datasets easily usable for future research.

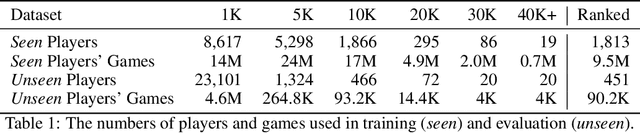

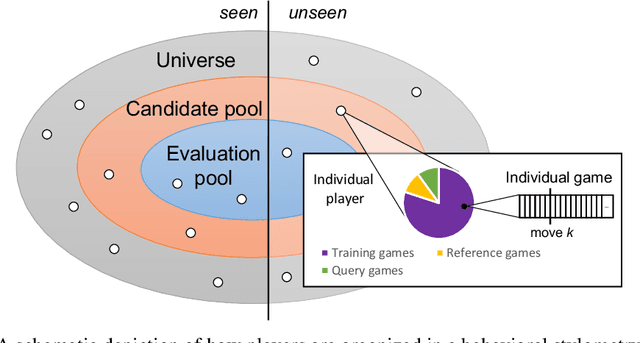

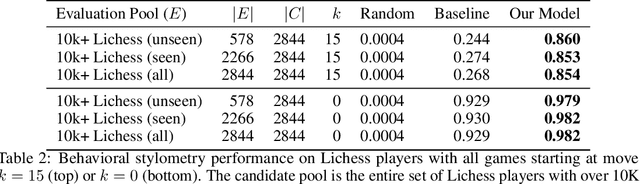

Detecting Individual Decision-Making Style: Exploring Behavioral Stylometry in Chess

Aug 02, 2022

Abstract:The advent of machine learning models that surpass human decision-making ability in complex domains has initiated a movement towards building AI systems that interact with humans. Many building blocks are essential for this activity, with a central one being the algorithmic characterization of human behavior. While much of the existing work focuses on aggregate human behavior, an important long-range goal is to develop behavioral models that specialize to individual people and can differentiate among them. To formalize this process, we study the problem of behavioral stylometry, in which the task is to identify a decision-maker from their decisions alone. We present a transformer-based approach to behavioral stylometry in the context of chess, where one attempts to identify the player who played a set of games. Our method operates in a few-shot classification framework, and can correctly identify a player from among thousands of candidate players with 98% accuracy given only 100 labeled games. Even when trained on amateur play, our method generalises to out-of-distribution samples of Grandmaster players, despite the dramatic differences between amateur and world-class players. Finally, we consider more broadly what our resulting embeddings reveal about human style in chess, as well as the potential ethical implications of powerful methods for identifying individuals from behavioral data.

Mimetic Models: Ethical Implications of AI that Acts Like You

Jul 19, 2022Abstract:An emerging theme in artificial intelligence research is the creation of models to simulate the decisions and behavior of specific people, in domains including game-playing, text generation, and artistic expression. These models go beyond earlier approaches in the way they are tailored to individuals, and the way they are designed for interaction rather than simply the reproduction of fixed, pre-computed behaviors. We refer to these as mimetic models, and in this paper we develop a framework for characterizing the ethical and social issues raised by their growing availability. Our framework includes a number of distinct scenarios for the use of such models, and considers the impacts on a range of different participants, including the target being modeled, the operator who deploys the model, and the entities that interact with it.

Measuring the Effect of Training Data on Deep Learning Predictions via Randomized Experiments

Jun 20, 2022

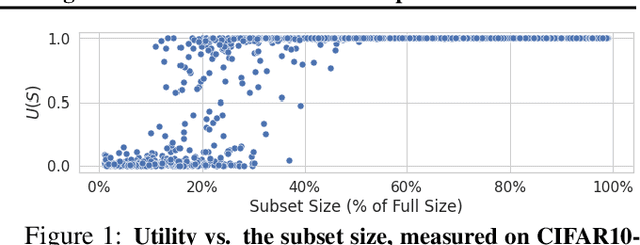

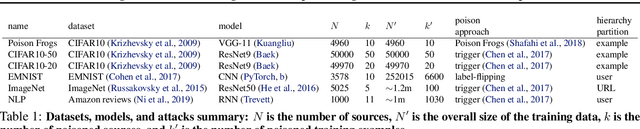

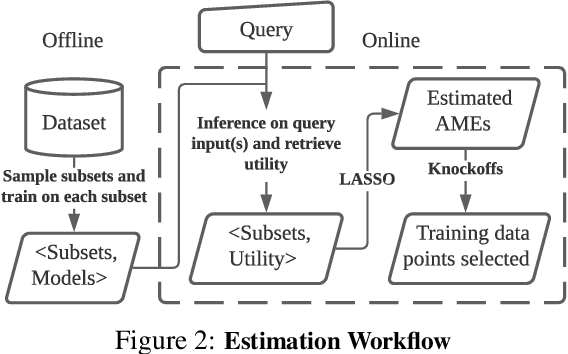

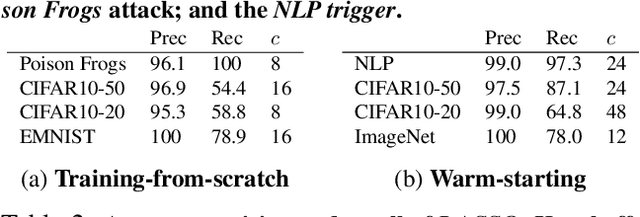

Abstract:We develop a new, principled algorithm for estimating the contribution of training data points to the behavior of a deep learning model, such as a specific prediction it makes. Our algorithm estimates the AME, a quantity that measures the expected (average) marginal effect of adding a data point to a subset of the training data, sampled from a given distribution. When subsets are sampled from the uniform distribution, the AME reduces to the well-known Shapley value. Our approach is inspired by causal inference and randomized experiments: we sample different subsets of the training data to train multiple submodels, and evaluate each submodel's behavior. We then use a LASSO regression to jointly estimate the AME of each data point, based on the subset compositions. Under sparsity assumptions ($k \ll N$ datapoints have large AME), our estimator requires only $O(k\log N)$ randomized submodel trainings, improving upon the best prior Shapley value estimators.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge