David Patterson

Challenges and Research Directions for Large Language Model Inference Hardware

Jan 08, 2026Abstract:Large Language Model (LLM) inference is hard. The autoregressive Decode phase of the underlying Transformer model makes LLM inference fundamentally different from training. Exacerbated by recent AI trends, the primary challenges are memory and interconnect rather than compute. To address these challenges, we highlight four architecture research opportunities: High Bandwidth Flash for 10X memory capacity with HBM-like bandwidth; Processing-Near-Memory and 3D memory-logic stacking for high memory bandwidth; and low-latency interconnect to speedup communication. While our focus is datacenter AI, we also review their applicability for mobile devices.

Shaping AI's Impact on Billions of Lives

Dec 03, 2024

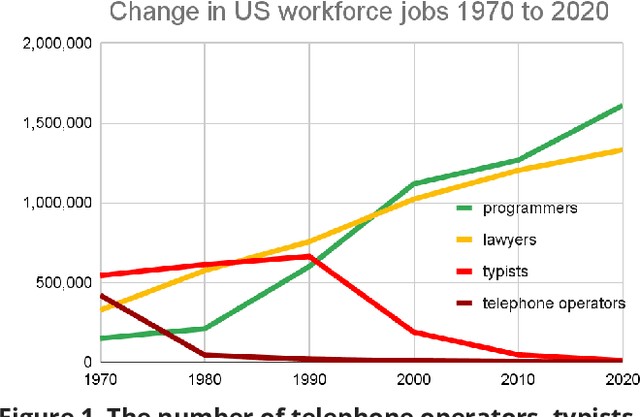

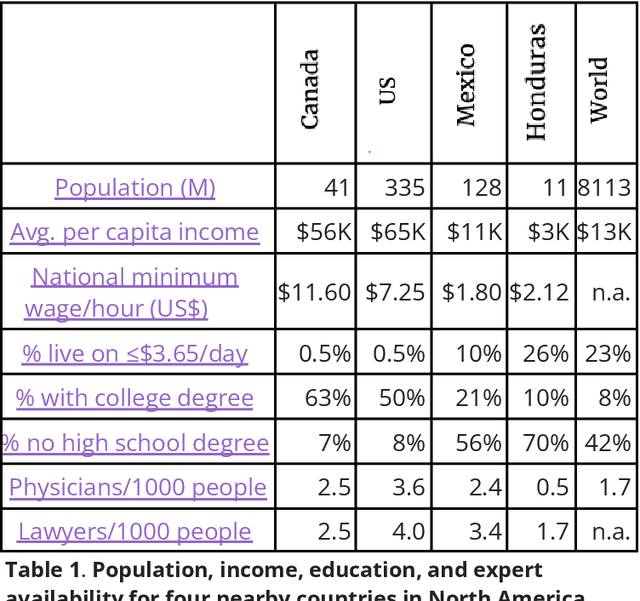

Abstract:Artificial Intelligence (AI), like any transformative technology, has the potential to be a double-edged sword, leading either toward significant advancements or detrimental outcomes for society as a whole. As is often the case when it comes to widely-used technologies in market economies (e.g., cars and semiconductor chips), commercial interest tends to be the predominant guiding factor. The AI community is at risk of becoming polarized to either take a laissez-faire attitude toward AI development, or to call for government overregulation. Between these two poles we argue for the community of AI practitioners to consciously and proactively work for the common good. This paper offers a blueprint for a new type of innovation infrastructure including 18 concrete milestones to guide AI research in that direction. Our view is that we are still in the early days of practical AI, and focused efforts by practitioners, policymakers, and other stakeholders can still maximize the upsides of AI and minimize its downsides. We talked to luminaries such as recent Nobelist John Jumper on science, President Barack Obama on governance, former UN Ambassador and former National Security Advisor Susan Rice on security, philanthropist Eric Schmidt on several topics, and science fiction novelist Neal Stephenson on entertainment. This ongoing dialogue and collaborative effort has produced a comprehensive, realistic view of what the actual impact of AI could be, from a diverse assembly of thinkers with deep understanding of this technology and these domains. From these exchanges, five recurring guidelines emerged, which form the cornerstone of a framework for beginning to harness AI in service of the public good. They not only guide our efforts in discovery but also shape our approach to deploying this transformative technology responsibly and ethically.

TPU v4: An Optically Reconfigurable Supercomputer for Machine Learning with Hardware Support for Embeddings

Apr 20, 2023Abstract:In response to innovations in machine learning (ML) models, production workloads changed radically and rapidly. TPU v4 is the fifth Google domain specific architecture (DSA) and its third supercomputer for such ML models. Optical circuit switches (OCSes) dynamically reconfigure its interconnect topology to improve scale, availability, utilization, modularity, deployment, security, power, and performance; users can pick a twisted 3D torus topology if desired. Much cheaper, lower power, and faster than Infiniband, OCSes and underlying optical components are <5% of system cost and <3% of system power. Each TPU v4 includes SparseCores, dataflow processors that accelerate models that rely on embeddings by 5x-7x yet use only 5% of die area and power. Deployed since 2020, TPU v4 outperforms TPU v3 by 2.1x and improves performance/Watt by 2.7x. The TPU v4 supercomputer is 4x larger at 4096 chips and thus ~10x faster overall, which along with OCS flexibility helps large language models. For similar sized systems, it is ~4.3x-4.5x faster than the Graphcore IPU Bow and is 1.2x-1.7x faster and uses 1.3x-1.9x less power than the Nvidia A100. TPU v4s inside the energy-optimized warehouse scale computers of Google Cloud use ~3x less energy and produce ~20x less CO2e than contemporary DSAs in a typical on-premise data center.

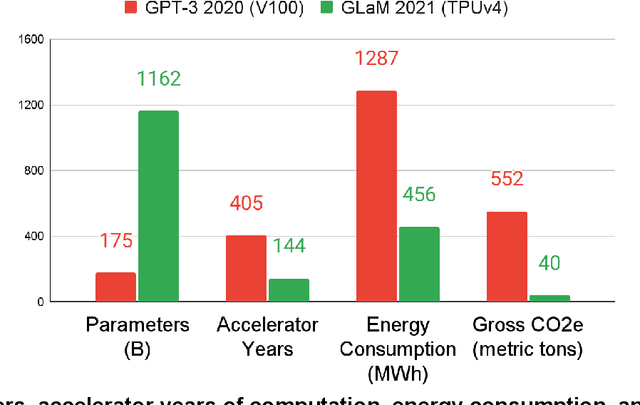

The Carbon Footprint of Machine Learning Training Will Plateau, Then Shrink

Apr 11, 2022

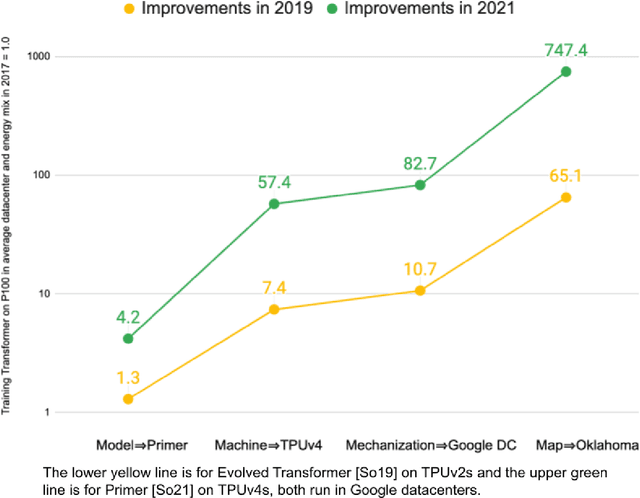

Abstract:Machine Learning (ML) workloads have rapidly grown in importance, but raised concerns about their carbon footprint. Four best practices can reduce ML training energy by up to 100x and CO2 emissions up to 1000x. By following best practices, overall ML energy use (across research, development, and production) held steady at <15% of Google's total energy use for the past three years. If the whole ML field were to adopt best practices, total carbon emissions from training would reduce. Hence, we recommend that ML papers include emissions explicitly to foster competition on more than just model quality. Estimates of emissions in papers that omitted them have been off 100x-100,000x, so publishing emissions has the added benefit of ensuring accurate accounting. Given the importance of climate change, we must get the numbers right to make certain that we work on its biggest challenges.

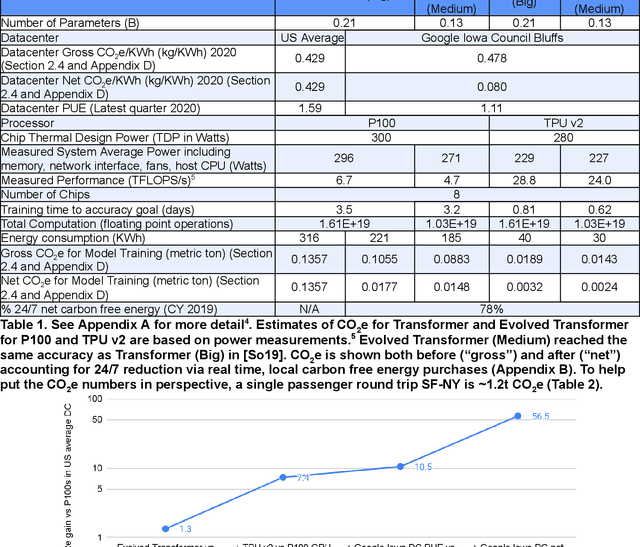

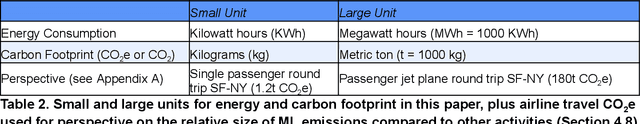

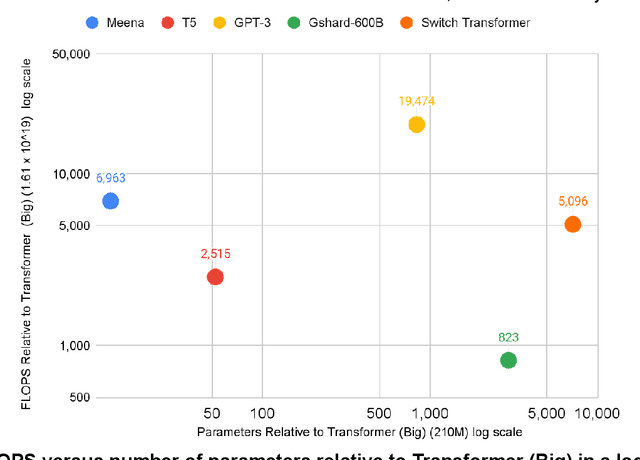

Carbon Emissions and Large Neural Network Training

Apr 23, 2021

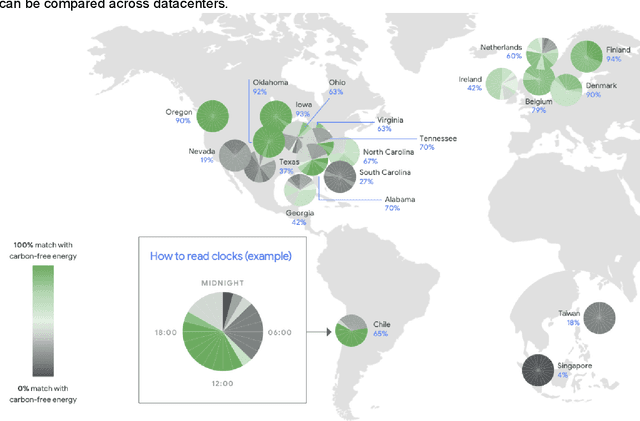

Abstract:The computation demand for machine learning (ML) has grown rapidly recently, which comes with a number of costs. Estimating the energy cost helps measure its environmental impact and finding greener strategies, yet it is challenging without detailed information. We calculate the energy use and carbon footprint of several recent large models-T5, Meena, GShard, Switch Transformer, and GPT-3-and refine earlier estimates for the neural architecture search that found Evolved Transformer. We highlight the following opportunities to improve energy efficiency and CO2 equivalent emissions (CO2e): Large but sparsely activated DNNs can consume <1/10th the energy of large, dense DNNs without sacrificing accuracy despite using as many or even more parameters. Geographic location matters for ML workload scheduling since the fraction of carbon-free energy and resulting CO2e vary ~5X-10X, even within the same country and the same organization. We are now optimizing where and when large models are trained. Specific datacenter infrastructure matters, as Cloud datacenters can be ~1.4-2X more energy efficient than typical datacenters, and the ML-oriented accelerators inside them can be ~2-5X more effective than off-the-shelf systems. Remarkably, the choice of DNN, datacenter, and processor can reduce the carbon footprint up to ~100-1000X. These large factors also make retroactive estimates of energy cost difficult. To avoid miscalculations, we believe ML papers requiring large computational resources should make energy consumption and CO2e explicit when practical. We are working to be more transparent about energy use and CO2e in our future research. To help reduce the carbon footprint of ML, we believe energy usage and CO2e should be a key metric in evaluating models, and we are collaborating with MLPerf developers to include energy usage during training and inference in this industry standard benchmark.

Benchmarking TinyML Systems: Challenges and Direction

Mar 10, 2020

Abstract:Recent advancements in ultra-low-power machine learning (TinyML) hardware promises to unlock an entirely new class of smart applications. However, continued progress is limited by the lack of a widely accepted benchmark for these systems. Benchmarking allows us to measure and thereby systematically compare, evaluate, and improve the performance of systems. In this position paper, we present the current landscape of TinyML and discuss the challenges and direction towards developing a fair and useful hardware benchmark for TinyML workloads. Our viewpoints reflect the collective thoughts of the TinyMLPerf working group that is comprised of 30 organizations.

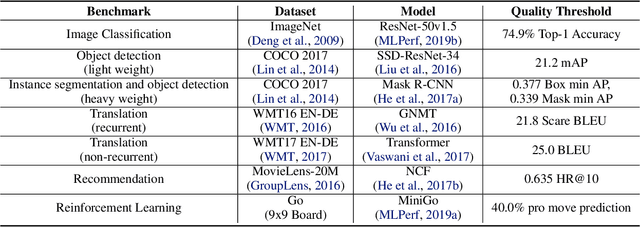

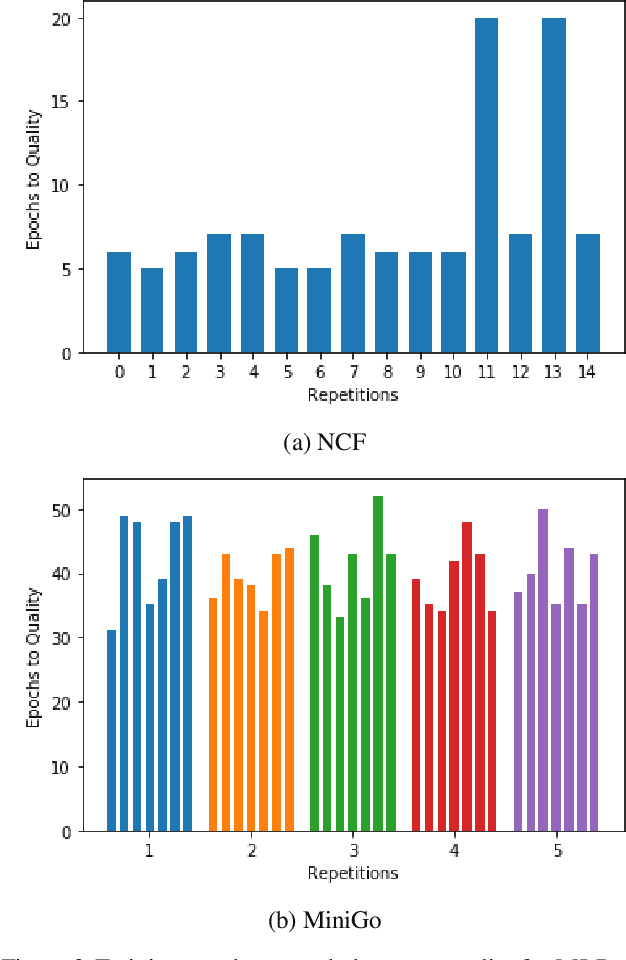

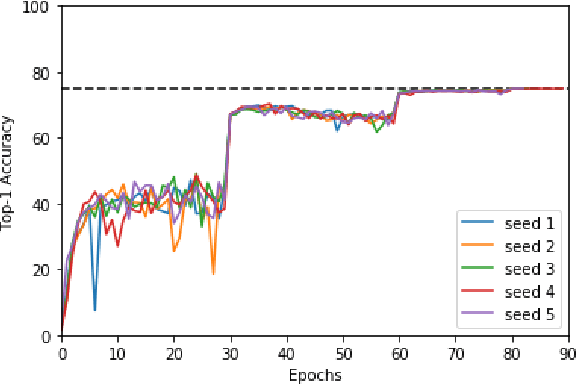

MLPerf Training Benchmark

Oct 30, 2019

Abstract:Machine learning is experiencing an explosion of software and hardware solutions, and needs industry-standard performance benchmarks to drive design and enable competitive evaluation. However, machine learning training presents a number of unique challenges to benchmarking that do not exist in other domains: (1) some optimizations that improve training throughput actually increase time to solution, (2) training is stochastic and time to solution has high variance, and (3) the software and hardware systems are so diverse that they cannot be fairly benchmarked with the same binary, code, or even hyperparameters. We present MLPerf, a machine learning benchmark that overcomes these challenges. We quantitatively evaluate the efficacy of MLPerf in driving community progress on performance and scalability across two rounds of results from multiple vendors.

A Berkeley View of Systems Challenges for AI

Dec 15, 2017

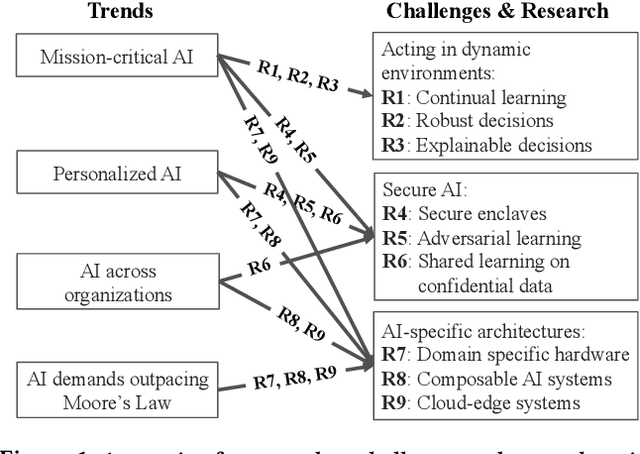

Abstract:With the increasing commoditization of computer vision, speech recognition and machine translation systems and the widespread deployment of learning-based back-end technologies such as digital advertising and intelligent infrastructures, AI (Artificial Intelligence) has moved from research labs to production. These changes have been made possible by unprecedented levels of data and computation, by methodological advances in machine learning, by innovations in systems software and architectures, and by the broad accessibility of these technologies. The next generation of AI systems promises to accelerate these developments and increasingly impact our lives via frequent interactions and making (often mission-critical) decisions on our behalf, often in highly personalized contexts. Realizing this promise, however, raises daunting challenges. In particular, we need AI systems that make timely and safe decisions in unpredictable environments, that are robust against sophisticated adversaries, and that can process ever increasing amounts of data across organizations and individuals without compromising confidentiality. These challenges will be exacerbated by the end of the Moore's Law, which will constrain the amount of data these technologies can store and process. In this paper, we propose several open research directions in systems, architectures, and security that can address these challenges and help unlock AI's potential to improve lives and society.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge