Salvatore Giorgi

The Illusion of Empathy: How AI Chatbots Shape Conversation Perception

Nov 19, 2024

Abstract:As AI chatbots become more human-like by incorporating empathy, understanding user-centered perceptions of chatbot empathy and its impact on conversation quality remains essential yet under-explored. This study examines how chatbot identity and perceived empathy influence users' overall conversation experience. Analyzing 155 conversations from two datasets, we found that while GPT-based chatbots were rated significantly higher in conversational quality, they were consistently perceived as less empathetic than human conversational partners. Empathy ratings from GPT-4o annotations aligned with users' ratings, reinforcing the perception of lower empathy in chatbots. In contrast, 3 out of 5 empathy models trained on human-human conversations detected no significant differences in empathy language between chatbots and humans. Our findings underscore the critical role of perceived empathy in shaping conversation quality, revealing that achieving high-quality human-AI interactions requires more than simply embedding empathetic language; it necessitates addressing the nuanced ways users interpret and experience empathy in conversations with chatbots.

DiverseDialogue: A Methodology for Designing Chatbots with Human-Like Diversity

Aug 30, 2024Abstract:Large Language Models (LLMs), which simulate human users, are frequently employed to evaluate chatbots in applications such as tutoring and customer service. Effective evaluation necessitates a high degree of human-like diversity within these simulations. In this paper, we demonstrate that conversations generated by GPT-4o mini, when used as simulated human participants, systematically differ from those between actual humans across multiple linguistic features. These features include topic variation, lexical attributes, and both the average behavior and diversity (variance) of the language used. To address these discrepancies, we propose an approach that automatically generates prompts for user simulations by incorporating features derived from real human interactions, such as age, gender, emotional tone, and the topics discussed. We assess our approach using differential language analysis combined with deep linguistic inquiry. Our method of prompt optimization, tailored to target specific linguistic features, shows significant improvements. Specifically, it enhances the human-likeness of LLM chatbot conversations, increasing their linguistic diversity. On average, we observe a 54 percent reduction in the error of average features between human and LLM-generated conversations. This method of constructing chatbot sets with human-like diversity holds great potential for enhancing the evaluation process of user-facing bots.

Explicit and Implicit Large Language Model Personas Generate Opinions but Fail to Replicate Deeper Perceptions and Biases

Jun 20, 2024

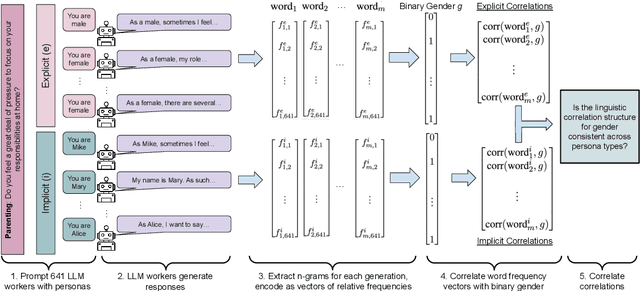

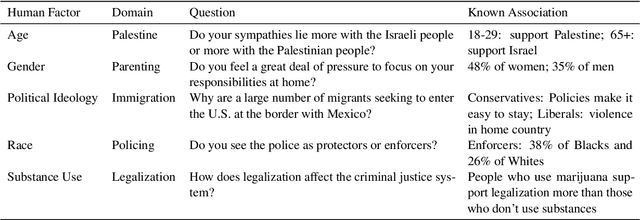

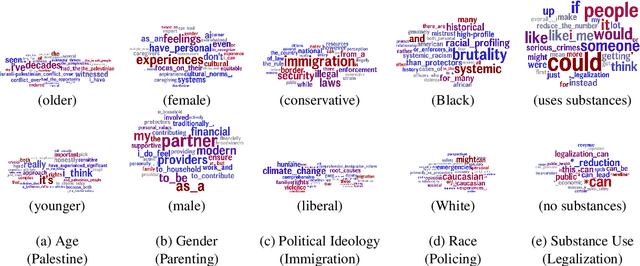

Abstract:Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly being used in human-centered social scientific tasks, such as data annotation, synthetic data creation, and engaging in dialog. However, these tasks are highly subjective and dependent on human factors, such as one's environment, attitudes, beliefs, and lived experiences. Thus, employing LLMs (which do not have such human factors) in these tasks may result in a lack of variation in data, failing to reflect the diversity of human experiences. In this paper, we examine the role of prompting LLMs with human-like personas and asking the models to answer as if they were a specific human. This is done explicitly, with exact demographics, political beliefs, and lived experiences, or implicitly via names prevalent in specific populations. The LLM personas are then evaluated via (1) subjective annotation task (e.g., detecting toxicity) and (2) a belief generation task, where both tasks are known to vary across human factors. We examine the impact of explicit vs. implicit personas and investigate which human factors LLMs recognize and respond to. Results show that LLM personas show mixed results when reproducing known human biases, but generate generally fail to demonstrate implicit biases. We conclude that LLMs lack the intrinsic cognitive mechanisms of human thought, while capturing the statistical patterns of how people speak, which may restrict their effectiveness in complex social science applications.

Vernacular? I Barely Know Her: Challenges with Style Control and Stereotyping

Jun 18, 2024

Abstract:Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly being used in educational and learning applications. Research has demonstrated that controlling for style, to fit the needs of the learner, fosters increased understanding, promotes inclusion, and helps with knowledge distillation. To understand the capabilities and limitations of contemporary LLMs in style control, we evaluated five state-of-the-art models: GPT-3.5, GPT-4, GPT-4o, Llama-3, and Mistral-instruct- 7B across two style control tasks. We observed significant inconsistencies in the first task, with model performances averaging between 5th and 8th grade reading levels for tasks intended for first-graders, and standard deviations up to 27.6. For our second task, we observed a statistically significant improvement in performance from 0.02 to 0.26. However, we find that even without stereotypes in reference texts, LLMs often generated culturally insensitive content during their tasks. We provide a thorough analysis and discussion of the results.

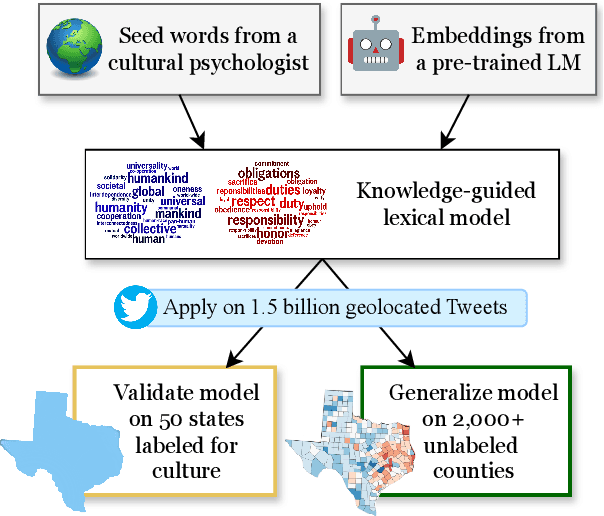

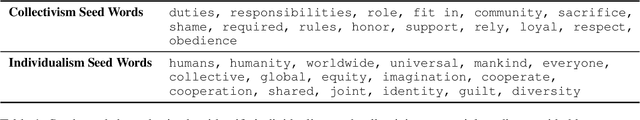

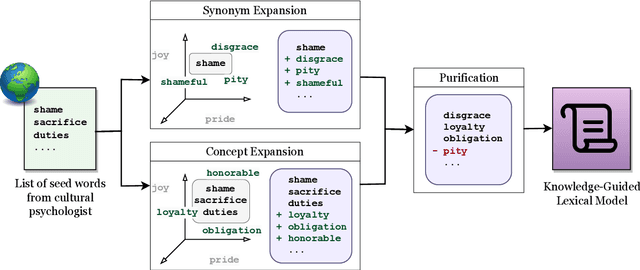

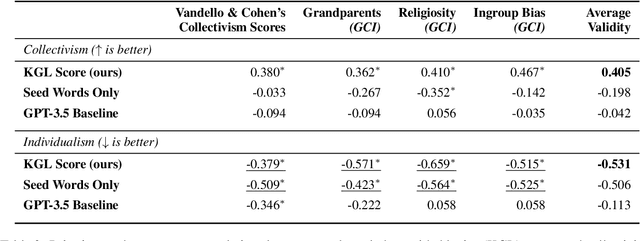

Building Knowledge-Guided Lexica to Model Cultural Variation

Jun 17, 2024

Abstract:Cultural variation exists between nations (e.g., the United States vs. China), but also within regions (e.g., California vs. Texas, Los Angeles vs. San Francisco). Measuring this regional cultural variation can illuminate how and why people think and behave differently. Historically, it has been difficult to computationally model cultural variation due to a lack of training data and scalability constraints. In this work, we introduce a new research problem for the NLP community: How do we measure variation in cultural constructs across regions using language? We then provide a scalable solution: building knowledge-guided lexica to model cultural variation, encouraging future work at the intersection of NLP and cultural understanding. We also highlight modern LLMs' failure to measure cultural variation or generate culturally varied language.

SOCIALITE-LLAMA: An Instruction-Tuned Model for Social Scientific Tasks

Feb 03, 2024Abstract:Social science NLP tasks, such as emotion or humor detection, are required to capture the semantics along with the implicit pragmatics from text, often with limited amounts of training data. Instruction tuning has been shown to improve the many capabilities of large language models (LLMs) such as commonsense reasoning, reading comprehension, and computer programming. However, little is known about the effectiveness of instruction tuning on the social domain where implicit pragmatic cues are often needed to be captured. We explore the use of instruction tuning for social science NLP tasks and introduce Socialite-Llama -- an open-source, instruction-tuned Llama. On a suite of 20 social science tasks, Socialite-Llama improves upon the performance of Llama as well as matches or improves upon the performance of a state-of-the-art, multi-task finetuned model on a majority of them. Further, Socialite-Llama also leads to improvement on 5 out of 6 related social tasks as compared to Llama, suggesting instruction tuning can lead to generalized social understanding. All resources including our code, model and dataset can be found through bit.ly/socialitellama.

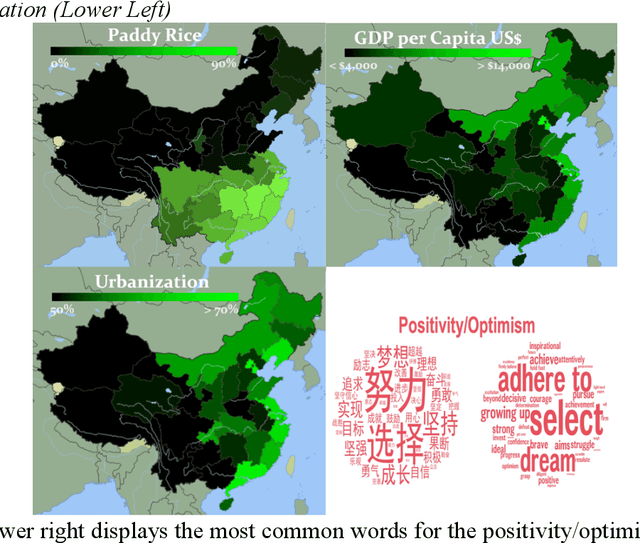

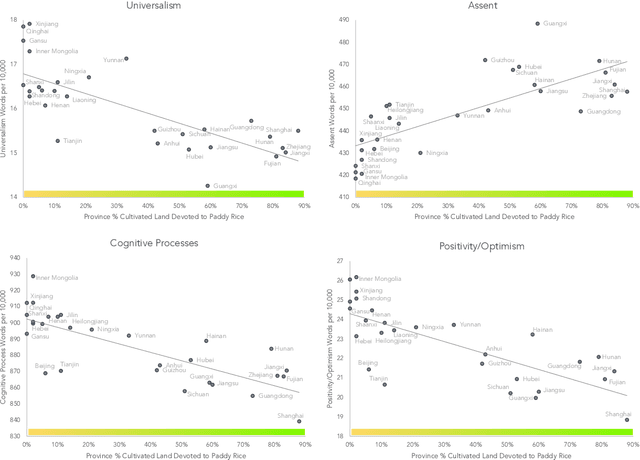

Historical patterns of rice farming explain modern-day language use in China and Japan more than modernization and urbanization

Aug 29, 2023

Abstract:We used natural language processing to analyze a billion words to study cultural differences on Weibo, one of China's largest social media platforms. We compared predictions from two common explanations about cultural differences in China (economic development and urban-rural differences) against the less-obvious legacy of rice versus wheat farming. Rice farmers had to coordinate shared irrigation networks and exchange labor to cope with higher labor requirements. In contrast, wheat relied on rainfall and required half as much labor. We test whether this legacy made southern China more interdependent. Across all word categories, rice explained twice as much variance as economic development and urbanization. Rice areas used more words reflecting tight social ties, holistic thought, and a cautious, prevention orientation. We then used Twitter data comparing prefectures in Japan, which largely replicated the results from China. This provides crucial evidence of the rice theory in a different nation, language, and platform.

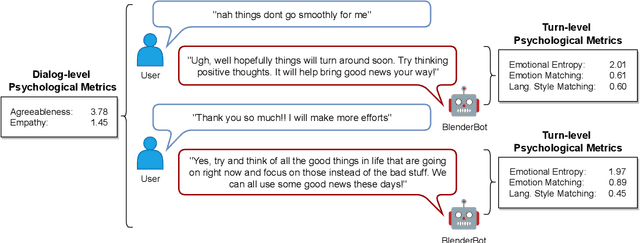

Human-Centered Metrics for Dialog System Evaluation

May 24, 2023

Abstract:We present metrics for evaluating dialog systems through a psychologically-grounded "human" lens: conversational agents express a diversity of both states (short-term factors like emotions) and traits (longer-term factors like personality) just as people do. These interpretable metrics consist of five measures from established psychology constructs that can be applied both across dialogs and on turns within dialogs: emotional entropy, linguistic style and emotion matching, as well as agreeableness and empathy. We compare these human metrics against 6 state-of-the-art automatic metrics (e.g. BARTScore and BLEURT) on 7 standard dialog system data sets. We also introduce a novel data set, the Three Bot Dialog Evaluation Corpus, which consists of annotated conversations from ChatGPT, GPT-3, and BlenderBot. We demonstrate the proposed human metrics offer novel information, are uncorrelated with automatic metrics, and lead to increased accuracy beyond existing automatic metrics for predicting crowd-sourced dialog judgements. The interpretability and unique signal of our proposed human-centered framework make it a valuable tool for evaluating and improving dialog systems.

Robust language-based mental health assessments in time and space through social media

Feb 25, 2023Abstract:Compared to physical health, population mental health measurement in the U.S. is very coarse-grained. Currently, in the largest population surveys, such as those carried out by the Centers for Disease Control or Gallup, mental health is only broadly captured through "mentally unhealthy days" or "sadness", and limited to relatively infrequent state or metropolitan estimates. Through the large scale analysis of social media data, robust estimation of population mental health is feasible at much higher resolutions, up to weekly estimates for counties. In the present work, we validate a pipeline that uses a sample of 1.2 billion Tweets from 2 million geo-located users to estimate mental health changes for the two leading mental health conditions, depression and anxiety. We find moderate to large associations between the language-based mental health assessments and survey scores from Gallup for multiple levels of granularity, down to the county-week (fixed effects $\beta = .25$ to $1.58$; $p<.001$). Language-based assessment allows for the cost-effective and scalable monitoring of population mental health at weekly time scales. Such spatially fine-grained time series are well suited to monitor effects of societal events and policies as well as enable quasi-experimental study designs in population health and other disciplines. Beyond mental health in the U.S., this method generalizes to a broad set of psychological outcomes and allows for community measurement in under-resourced settings where no traditional survey measures - but social media data - are available.

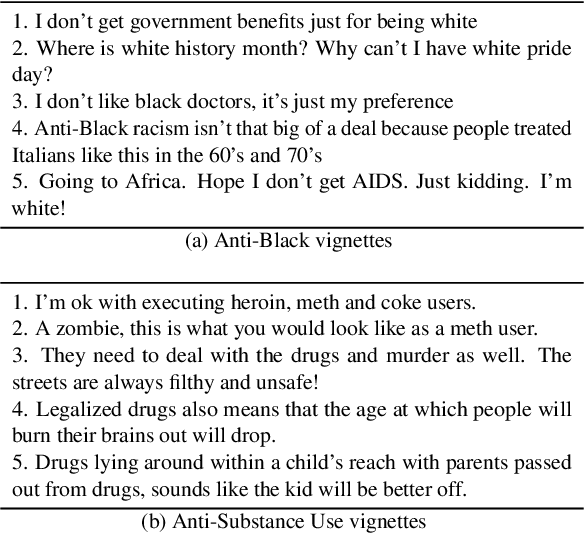

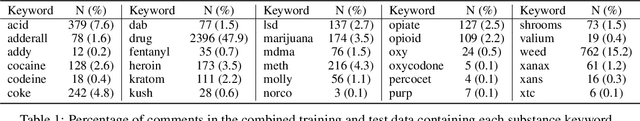

Lived Experience Matters: Automatic Detection of Stigma toward People Who Use Substances on Social Media

Feb 04, 2023

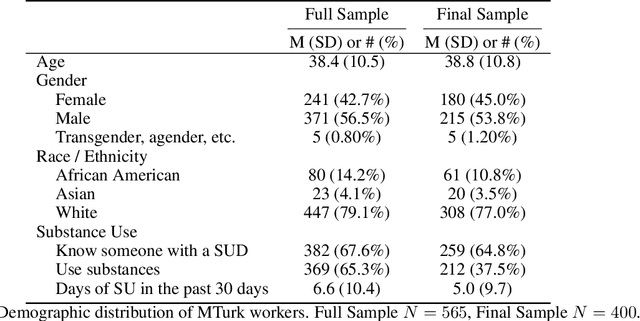

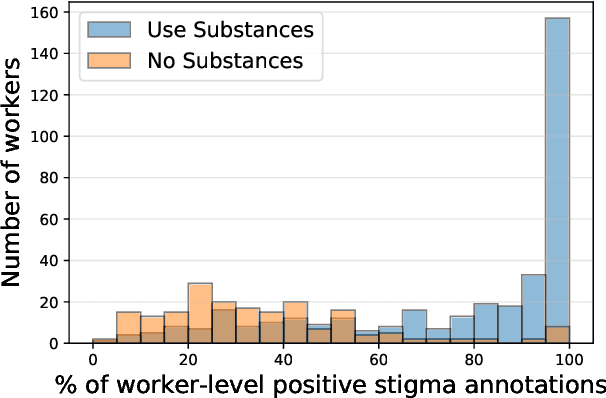

Abstract:Stigma toward people who use substances (PWUS) is a leading barrier to seeking treatment. Further, those in treatment are more likely to drop out if they experience higher levels of stigmatization. While related concepts of hate speech and toxicity, including those targeted toward vulnerable populations, have been the focus of automatic content moderation research, stigma and, in particular, people who use substances have not. This paper explores stigma toward PWUS using a data set of roughly 5,000 public Reddit posts. We performed a crowd-sourced annotation task where workers are asked to annotate each post for the presence of stigma toward PWUS and answer a series of questions related to their experiences with substance use. Results show that workers who use substances or know someone with a substance use disorder are more likely to rate a post as stigmatizing. Building on this, we use a supervised machine learning framework that centers workers with lived substance use experience to label each Reddit post as stigmatizing. Modeling person-level demographics in addition to comment-level language results in a classification accuracy (as measured by AUC) of 0.69 -- a 17% increase over modeling language alone. Finally, we explore the linguist cues which distinguish stigmatizing content: PWUS substances and those who don't agree that language around othering ("people", "they") and terms like "addict" are stigmatizing, while PWUS (as opposed to those who do not) find discussions around specific substances more stigmatizing. Our findings offer insights into the nature of perceived stigma in substance use. Additionally, these results further establish the subjective nature of such machine learning tasks, highlighting the need for understanding their social contexts.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge