Eric Schulz

Can vision language models learn intuitive physics from interaction?

Feb 05, 2026Abstract:Pre-trained vision language models do not have good intuitions about the physical world. Recent work has shown that supervised fine-tuning can improve model performance on simple physical tasks. However, fine-tuned models do not appear to learn robust physical rules that can generalize to new contexts. Based on research in cognitive science, we hypothesize that models need to interact with an environment to properly learn its physical dynamics. We train models that learn through interaction with the environment using reinforcement learning. While learning from interaction allows models to improve their within-task performance, it fails to produce models with generalizable physical intuitions. We find that models trained on one task do not reliably generalize to related tasks, even if the tasks share visual statistics and physical principles, and regardless of whether the models are trained through interaction.

Exploring System 1 and 2 communication for latent reasoning in LLMs

Oct 01, 2025Abstract:Should LLM reasoning live in a separate module, or within a single model's forward pass and representational space? We study dual-architecture latent reasoning, where a fluent Base exchanges latent messages with a Coprocessor, and test two hypotheses aimed at improving latent communication over Liu et al. (2024): (H1) increase channel capacity; (H2) learn communication via joint finetuning. Under matched latent-token budgets on GPT-2 and Qwen-3, H2 is consistently strongest while H1 yields modest gains. A unified soft-embedding baseline, a single model with the same forward pass and shared representations, using the same latent-token budget, nearly matches H2 and surpasses H1, suggesting current dual designs mostly add compute rather than qualitatively improving reasoning. Across GSM8K, ProsQA, and a Countdown stress test with increasing branching factor, scaling the latent-token budget beyond small values fails to improve robustness. Latent analyses show overlapping subspaces with limited specialization, consistent with weak reasoning gains. We conclude dual-model latent reasoning remains promising in principle, but likely requires objectives and communication mechanisms that explicitly shape latent spaces for algorithmic planning.

Automated scientific minimization of regret

May 23, 2025Abstract:We introduce automated scientific minimization of regret (ASMR) -- a framework for automated computational cognitive science. Building on the principles of scientific regret minimization, ASMR leverages Centaur -- a recently proposed foundation model of human cognition -- to identify gaps in an interpretable cognitive model. These gaps are then addressed through automated revisions generated by a language-based reasoning model. We demonstrate the utility of this approach in a multi-attribute decision-making task, showing that ASMR discovers cognitive models that predict human behavior at noise ceiling while retaining interpretability. Taken together, our results highlight the potential of ASMR to automate core components of the cognitive modeling pipeline.

Concept-Guided Interpretability via Neural Chunking

May 16, 2025

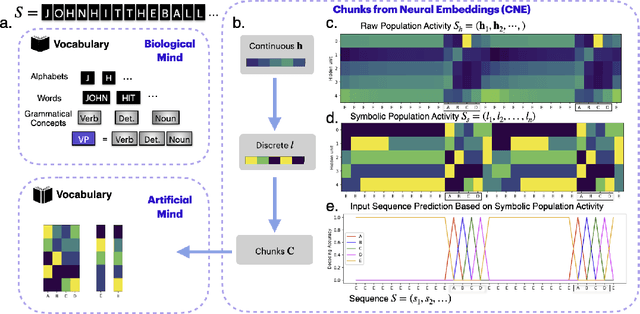

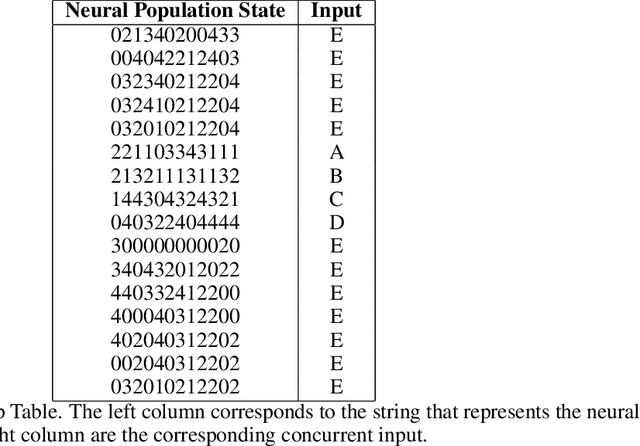

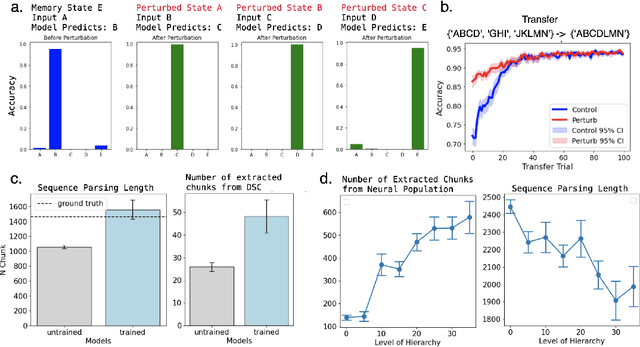

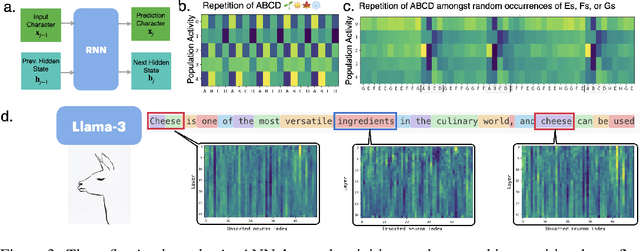

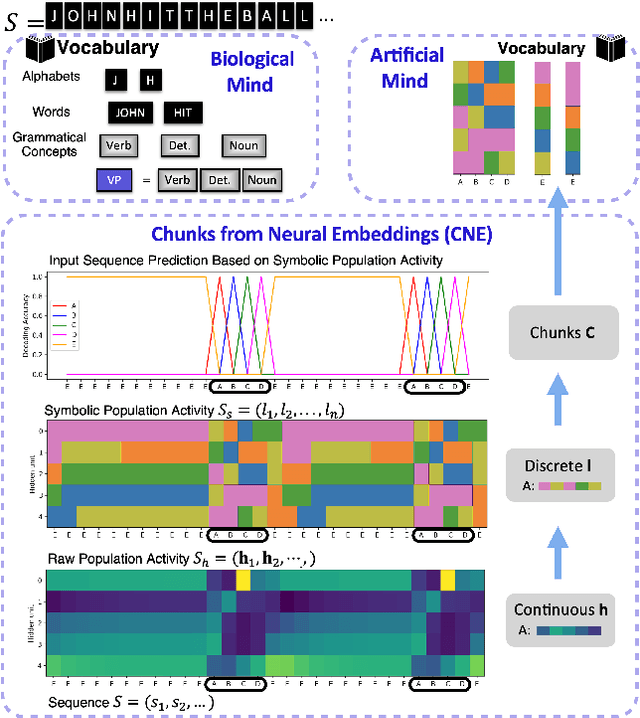

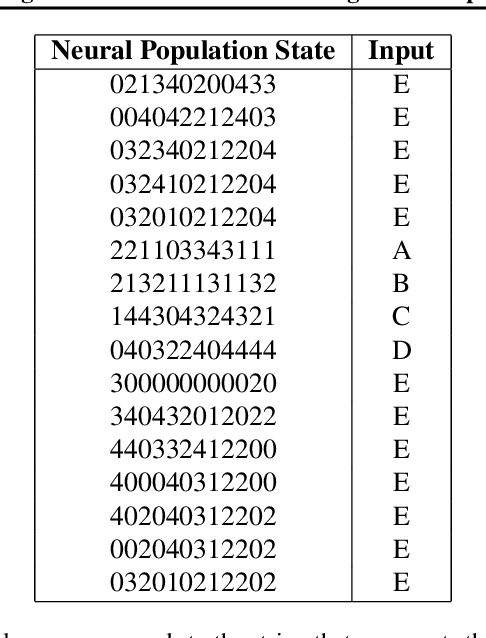

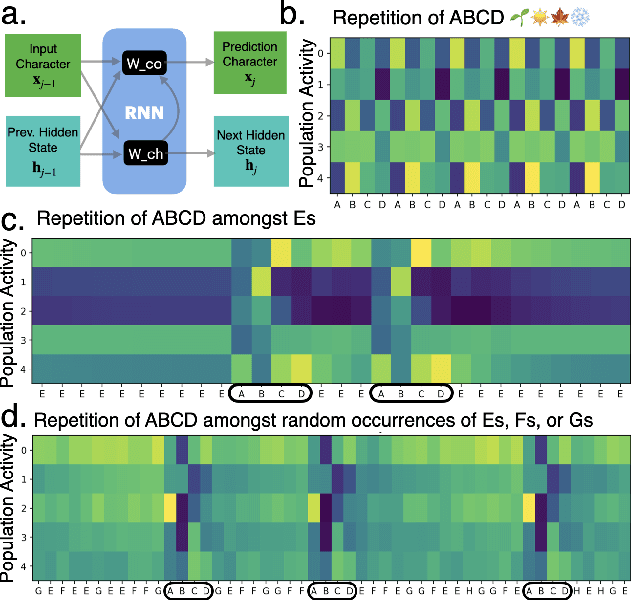

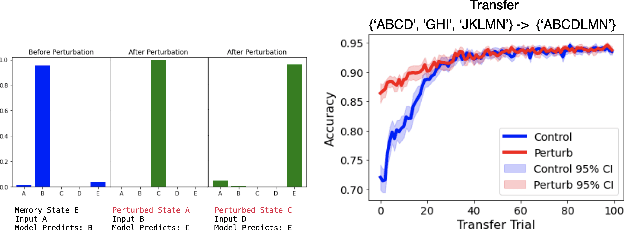

Abstract:Neural networks are often black boxes, reflecting the significant challenge of understanding their internal workings. We propose a different perspective that challenges the prevailing view: rather than being inscrutable, neural networks exhibit patterns in their raw population activity that mirror regularities in the training data. We refer to this as the Reflection Hypothesis and provide evidence for this phenomenon in both simple recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and complex large language models (LLMs). Building on this insight, we propose to leverage cognitively-inspired methods of chunking to segment high-dimensional neural population dynamics into interpretable units that reflect underlying concepts. We propose three methods to extract these emerging entities, complementing each other based on label availability and dimensionality. Discrete sequence chunking (DSC) creates a dictionary of entities; population averaging (PA) extracts recurring entities that correspond to known labels; and unsupervised chunk discovery (UCD) can be used when labels are absent. We demonstrate the effectiveness of these methods in extracting entities across varying model sizes, ranging from inducing compositionality in RNNs to uncovering recurring neural population states in large models with diverse architectures, and illustrate their advantage over other methods. Throughout, we observe a robust correspondence between the extracted entities and concrete or abstract concepts. Artificially inducing the extracted entities in neural populations effectively alters the network's generation of associated concepts. Our work points to a new direction for interpretability, one that harnesses both cognitive principles and the structure of naturalistic data to reveal the hidden computations of complex learning systems, gradually transforming them from black boxes into systems we can begin to understand.

Bringing Comparative Cognition To Computers

Mar 04, 2025Abstract:Researchers are increasingly subjecting artificial intelligence systems to psychological testing. But to rigorously compare their cognitive capacities with humans and other animals, we must avoid both over- and under-stating our similarities and differences. By embracing a comparative approach, we can integrate AI cognition research into the broader cognitive sciences.

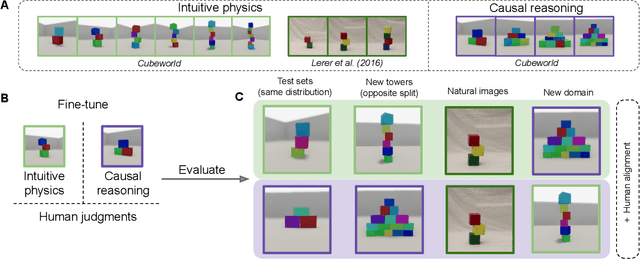

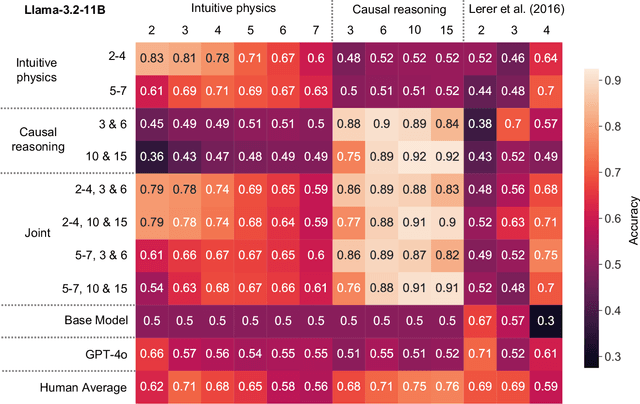

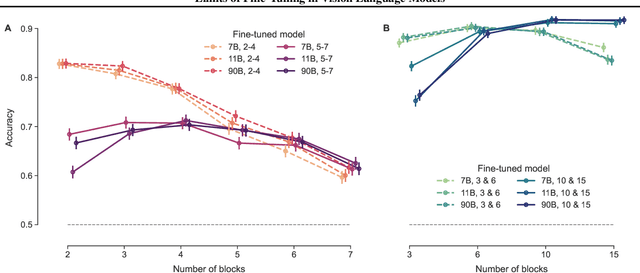

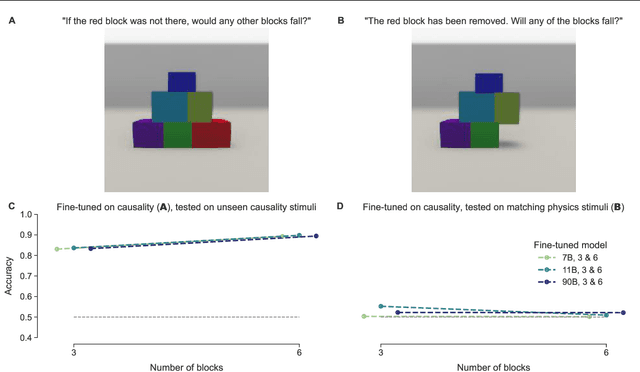

Testing the limits of fine-tuning to improve reasoning in vision language models

Feb 21, 2025

Abstract:Pre-trained vision language models still fall short of human visual cognition. In an effort to improve visual cognition and align models with human behavior, we introduce visual stimuli and human judgments on visual cognition tasks, allowing us to systematically evaluate performance across cognitive domains under a consistent environment. We fine-tune models on ground truth data for intuitive physics and causal reasoning and find that this improves model performance in the respective fine-tuning domain. Furthermore, it can improve model alignment with human behavior. However, we find that fine-tuning does not contribute to robust human-like generalization to data with other visual characteristics or to tasks in other cognitive domains.

Discovering Chunks in Neural Embeddings for Interpretability

Feb 03, 2025

Abstract:Understanding neural networks is challenging due to their high-dimensional, interacting components. Inspired by human cognition, which processes complex sensory data by chunking it into recurring entities, we propose leveraging this principle to interpret artificial neural population activities. Biological and artificial intelligence share the challenge of learning from structured, naturalistic data, and we hypothesize that the cognitive mechanism of chunking can provide insights into artificial systems. We first demonstrate this concept in recurrent neural networks (RNNs) trained on artificial sequences with imposed regularities, observing that their hidden states reflect these patterns, which can be extracted as a dictionary of chunks that influence network responses. Extending this to large language models (LLMs) like LLaMA, we identify similar recurring embedding states corresponding to concepts in the input, with perturbations to these states activating or inhibiting the associated concepts. By exploring methods to extract dictionaries of identifiable chunks across neural embeddings of varying complexity, our findings introduce a new framework for interpreting neural networks, framing their population activity as structured reflections of the data they process.

Towards Automation of Cognitive Modeling using Large Language Models

Feb 02, 2025

Abstract:Computational cognitive models, which formalize theories of cognition, enable researchers to quantify cognitive processes and arbitrate between competing theories by fitting models to behavioral data. Traditionally, these models are handcrafted, which requires significant domain knowledge, coding expertise, and time investment. Previous work has demonstrated that Large Language Models (LLMs) are adept at pattern recognition in-context, solving complex problems, and generating executable code. In this work, we leverage these abilities to explore the potential of LLMs in automating the generation of cognitive models based on behavioral data. We evaluated the LLM in two different tasks: model identification (relating data to a source model), and model generation (generating the underlying cognitive model). We performed these tasks across two cognitive domains - decision making and learning. In the case of data simulated from canonical cognitive models, we found that the LLM successfully identified and generated the ground truth model. In the case of human data, where behavioral noise and lack of knowledge of the true underlying process pose significant challenges, the LLM generated models that are identical or close to the winning model from cognitive science literature. Our findings suggest that LLMs can have a transformative impact on cognitive modeling. With this project, we aim to contribute to an ongoing effort of automating scientific discovery in cognitive science.

Building, Reusing, and Generalizing Abstract Representations from Concrete Sequences

Oct 27, 2024

Abstract:Humans excel at learning abstract patterns across different sequences, filtering out irrelevant details, and transferring these generalized concepts to new sequences. In contrast, many sequence learning models lack the ability to abstract, which leads to memory inefficiency and poor transfer. We introduce a non-parametric hierarchical variable learning model (HVM) that learns chunks from sequences and abstracts contextually similar chunks as variables. HVM efficiently organizes memory while uncovering abstractions, leading to compact sequence representations. When learning on language datasets such as babyLM, HVM learns a more efficient dictionary than standard compression algorithms such as Lempel-Ziv. In a sequence recall task requiring the acquisition and transfer of variables embedded in sequences, we demonstrate HVM's sequence likelihood correlates with human recall times. In contrast, large language models (LLMs) struggle to transfer abstract variables as effectively as humans. From HVM's adjustable layer of abstraction, we demonstrate that the model realizes a precise trade-off between compression and generalization. Our work offers a cognitive model that captures the learning and transfer of abstract representations in human cognition and differentiates itself from the behavior of large language models.

Centaur: a foundation model of human cognition

Oct 26, 2024

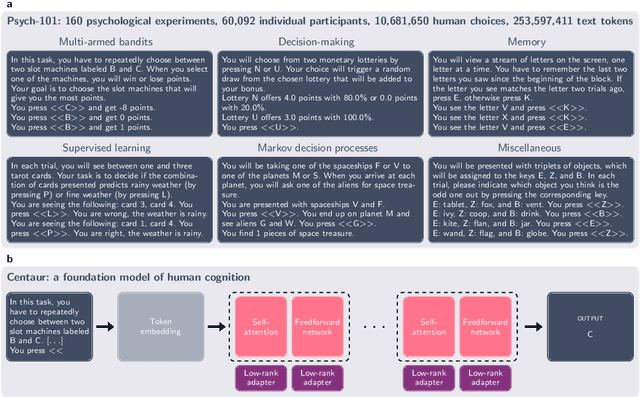

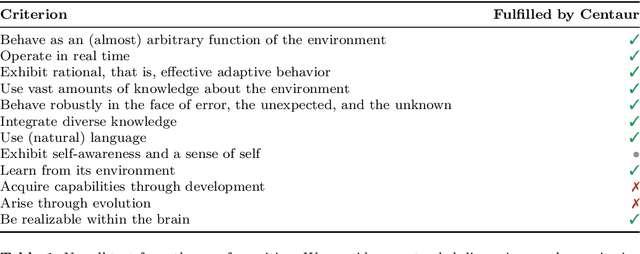

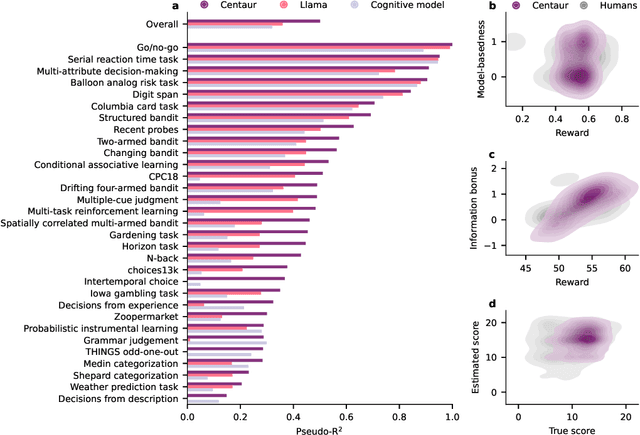

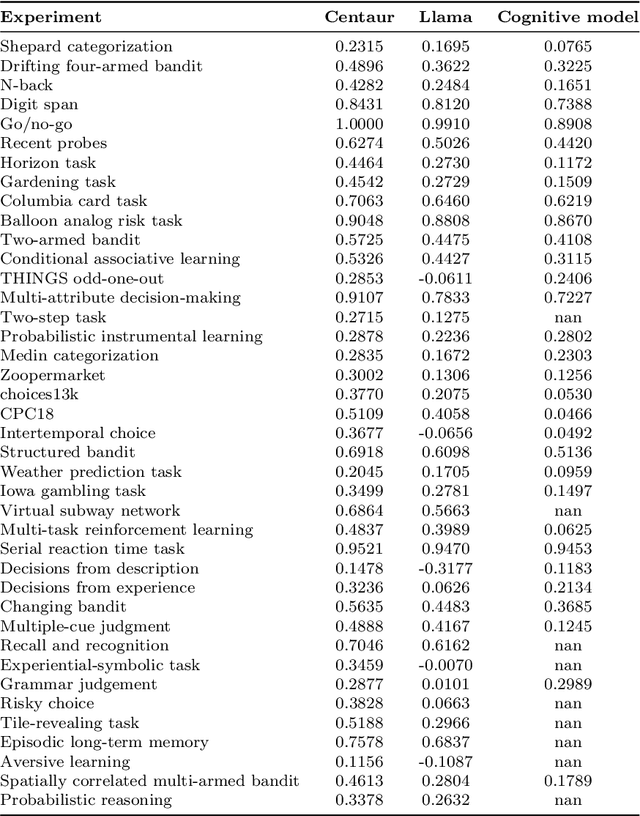

Abstract:Establishing a unified theory of cognition has been a major goal of psychology. While there have been previous attempts to instantiate such theories by building computational models, we currently do not have one model that captures the human mind in its entirety. Here we introduce Centaur, a computational model that can predict and simulate human behavior in any experiment expressible in natural language. We derived Centaur by finetuning a state-of-the-art language model on a novel, large-scale data set called Psych-101. Psych-101 reaches an unprecedented scale, covering trial-by-trial data from over 60,000 participants performing over 10,000,000 choices in 160 experiments. Centaur not only captures the behavior of held-out participants better than existing cognitive models, but also generalizes to new cover stories, structural task modifications, and entirely new domains. Furthermore, we find that the model's internal representations become more aligned with human neural activity after finetuning. Taken together, Centaur is the first real candidate for a unified model of human cognition. We anticipate that it will have a disruptive impact on the cognitive sciences, challenging the existing paradigm for developing computational models.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge