Marcel Binz

Automated scientific minimization of regret

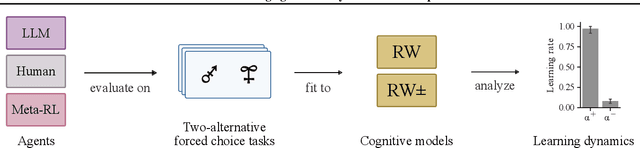

May 23, 2025Abstract:We introduce automated scientific minimization of regret (ASMR) -- a framework for automated computational cognitive science. Building on the principles of scientific regret minimization, ASMR leverages Centaur -- a recently proposed foundation model of human cognition -- to identify gaps in an interpretable cognitive model. These gaps are then addressed through automated revisions generated by a language-based reasoning model. We demonstrate the utility of this approach in a multi-attribute decision-making task, showing that ASMR discovers cognitive models that predict human behavior at noise ceiling while retaining interpretability. Taken together, our results highlight the potential of ASMR to automate core components of the cognitive modeling pipeline.

Centaur: a foundation model of human cognition

Oct 26, 2024

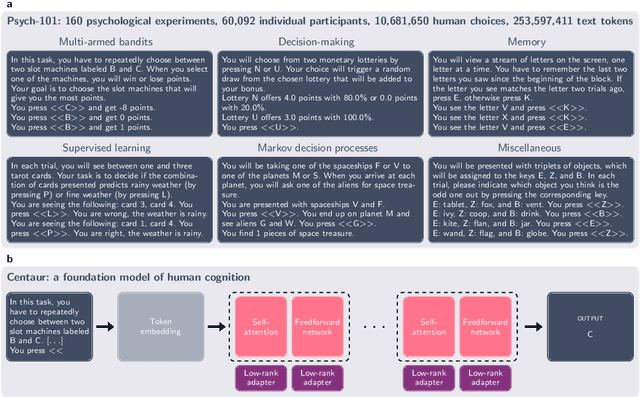

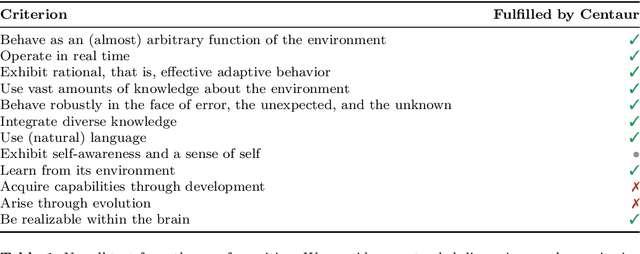

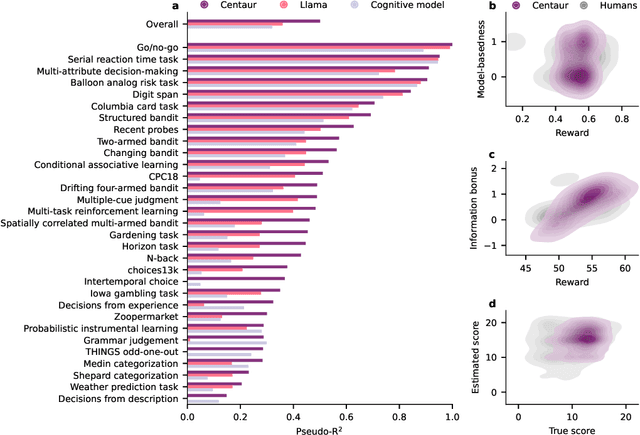

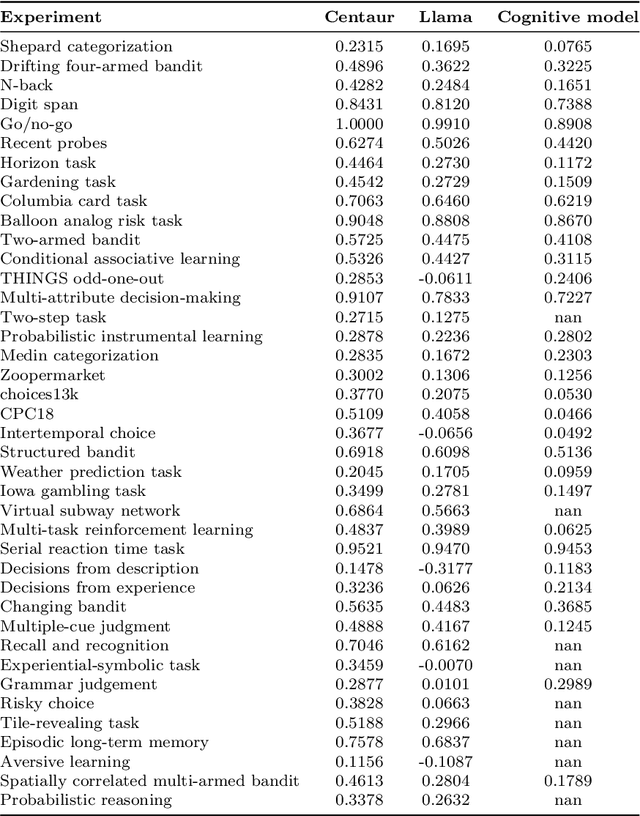

Abstract:Establishing a unified theory of cognition has been a major goal of psychology. While there have been previous attempts to instantiate such theories by building computational models, we currently do not have one model that captures the human mind in its entirety. Here we introduce Centaur, a computational model that can predict and simulate human behavior in any experiment expressible in natural language. We derived Centaur by finetuning a state-of-the-art language model on a novel, large-scale data set called Psych-101. Psych-101 reaches an unprecedented scale, covering trial-by-trial data from over 60,000 participants performing over 10,000,000 choices in 160 experiments. Centaur not only captures the behavior of held-out participants better than existing cognitive models, but also generalizes to new cover stories, structural task modifications, and entirely new domains. Furthermore, we find that the model's internal representations become more aligned with human neural activity after finetuning. Taken together, Centaur is the first real candidate for a unified model of human cognition. We anticipate that it will have a disruptive impact on the cognitive sciences, challenging the existing paradigm for developing computational models.

Sparse Autoencoders Reveal Temporal Difference Learning in Large Language Models

Oct 02, 2024

Abstract:In-context learning, the ability to adapt based on a few examples in the input prompt, is a ubiquitous feature of large language models (LLMs). However, as LLMs' in-context learning abilities continue to improve, understanding this phenomenon mechanistically becomes increasingly important. In particular, it is not well-understood how LLMs learn to solve specific classes of problems, such as reinforcement learning (RL) problems, in-context. Through three different tasks, we first show that Llama $3$ $70$B can solve simple RL problems in-context. We then analyze the residual stream of Llama using Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) and find representations that closely match temporal difference (TD) errors. Notably, these representations emerge despite the model only being trained to predict the next token. We verify that these representations are indeed causally involved in the computation of TD errors and $Q$-values by performing carefully designed interventions on them. Taken together, our work establishes a methodology for studying and manipulating in-context learning with SAEs, paving the way for a more mechanistic understanding.

CogBench: a large language model walks into a psychology lab

Feb 28, 2024

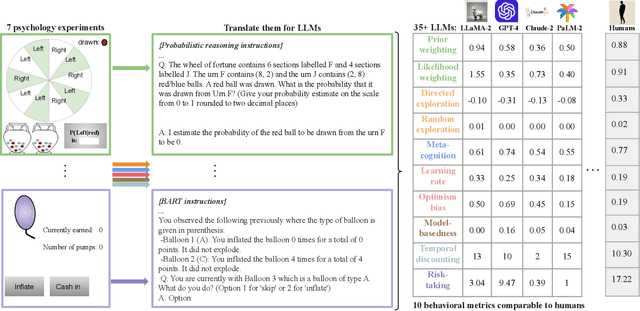

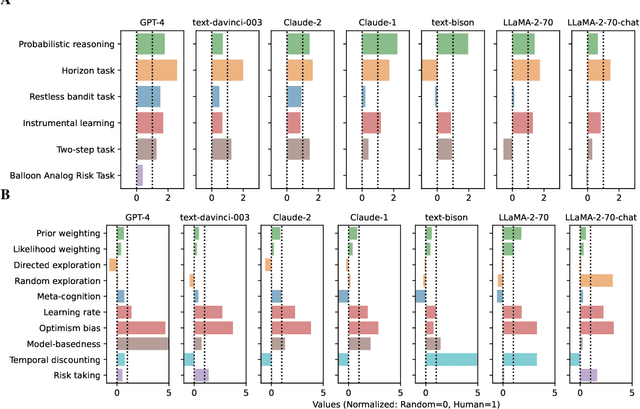

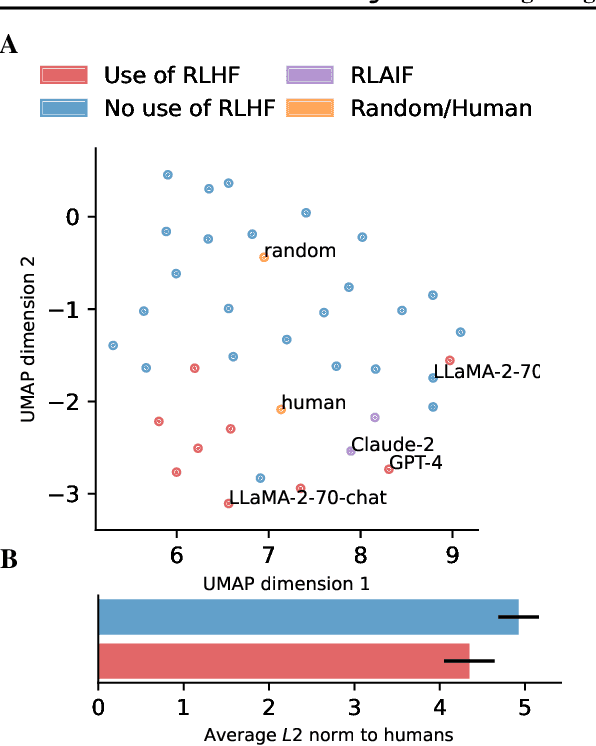

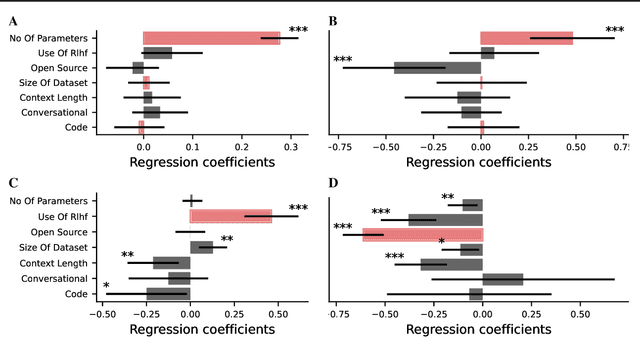

Abstract:Large language models (LLMs) have significantly advanced the field of artificial intelligence. Yet, evaluating them comprehensively remains challenging. We argue that this is partly due to the predominant focus on performance metrics in most benchmarks. This paper introduces CogBench, a benchmark that includes ten behavioral metrics derived from seven cognitive psychology experiments. This novel approach offers a toolkit for phenotyping LLMs' behavior. We apply CogBench to 35 LLMs, yielding a rich and diverse dataset. We analyze this data using statistical multilevel modeling techniques, accounting for the nested dependencies among fine-tuned versions of specific LLMs. Our study highlights the crucial role of model size and reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) in improving performance and aligning with human behavior. Interestingly, we find that open-source models are less risk-prone than proprietary models and that fine-tuning on code does not necessarily enhance LLMs' behavior. Finally, we explore the effects of prompt-engineering techniques. We discover that chain-of-thought prompting improves probabilistic reasoning, while take-a-step-back prompting fosters model-based behaviors.

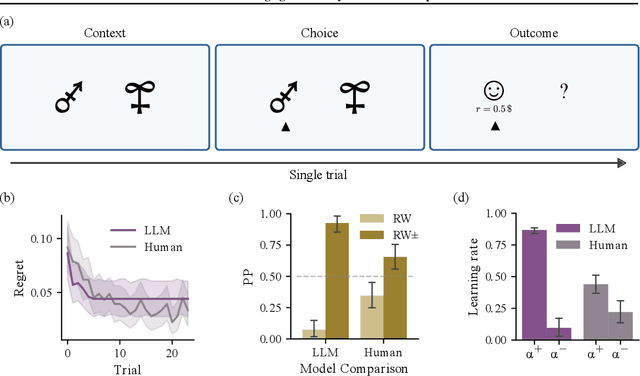

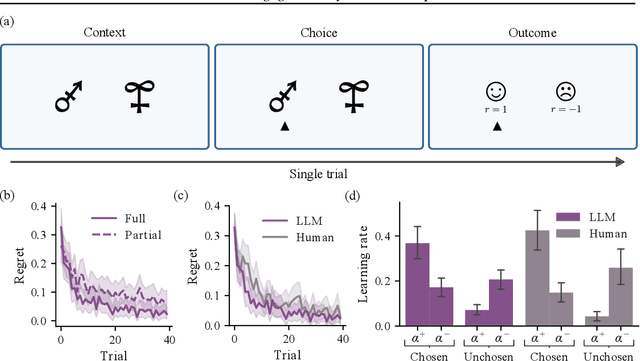

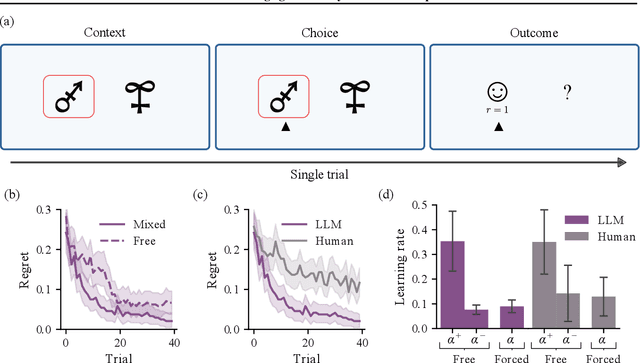

In-context learning agents are asymmetric belief updaters

Feb 06, 2024

Abstract:We study the in-context learning dynamics of large language models (LLMs) using three instrumental learning tasks adapted from cognitive psychology. We find that LLMs update their beliefs in an asymmetric manner and learn more from better-than-expected outcomes than from worse-than-expected ones. Furthermore, we show that this effect reverses when learning about counterfactual feedback and disappears when no agency is implied. We corroborate these findings by investigating idealized in-context learning agents derived through meta-reinforcement learning, where we observe similar patterns. Taken together, our results contribute to our understanding of how in-context learning works by highlighting that the framing of a problem significantly influences how learning occurs, a phenomenon also observed in human cognition.

Ecologically rational meta-learned inference explains human category learning

Feb 02, 2024Abstract:Ecological rationality refers to the notion that humans are rational agents adapted to their environment. However, testing this theory remains challenging due to two reasons: the difficulty in defining what tasks are ecologically valid and building rational models for these tasks. In this work, we demonstrate that large language models can generate cognitive tasks, specifically category learning tasks, that match the statistics of real-world tasks, thereby addressing the first challenge. We tackle the second challenge by deriving rational agents adapted to these tasks using the framework of meta-learning, leading to a class of models called ecologically rational meta-learned inference (ERMI). ERMI quantitatively explains human data better than seven other cognitive models in two different experiments. It additionally matches human behavior on a qualitative level: (1) it finds the same tasks difficult that humans find difficult, (2) it becomes more reliant on an exemplar-based strategy for assigning categories with learning, and (3) it generalizes to unseen stimuli in a human-like way. Furthermore, we show that ERMI's ecologically valid priors allow it to achieve state-of-the-art performance on the OpenML-CC18 classification benchmark.

How should the advent of large language models affect the practice of science?

Dec 05, 2023Abstract:Large language models (LLMs) are being increasingly incorporated into scientific workflows. However, we have yet to fully grasp the implications of this integration. How should the advent of large language models affect the practice of science? For this opinion piece, we have invited four diverse groups of scientists to reflect on this query, sharing their perspectives and engaging in debate. Schulz et al. make the argument that working with LLMs is not fundamentally different from working with human collaborators, while Bender et al. argue that LLMs are often misused and over-hyped, and that their limitations warrant a focus on more specialized, easily interpretable tools. Marelli et al. emphasize the importance of transparent attribution and responsible use of LLMs. Finally, Botvinick and Gershman advocate that humans should retain responsibility for determining the scientific roadmap. To facilitate the discussion, the four perspectives are complemented with a response from each group. By putting these different perspectives in conversation, we aim to bring attention to important considerations within the academic community regarding the adoption of LLMs and their impact on both current and future scientific practices.

The Acquisition of Physical Knowledge in Generative Neural Networks

Oct 30, 2023

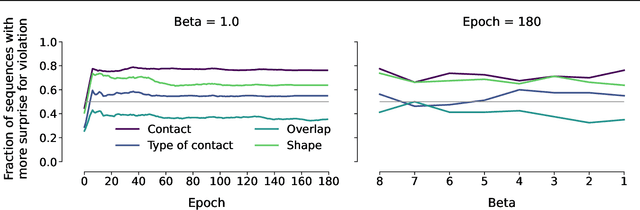

Abstract:As children grow older, they develop an intuitive understanding of the physical processes around them. Their physical understanding develops in stages, moving along developmental trajectories which have been mapped out extensively in previous empirical research. Here, we investigate how the learning trajectories of deep generative neural networks compare to children's developmental trajectories using physical understanding as a testbed. We outline an approach that allows us to examine two distinct hypotheses of human development - stochastic optimization and complexity increase. We find that while our models are able to accurately predict a number of physical processes, their learning trajectories under both hypotheses do not follow the developmental trajectories of children.

Language Aligned Visual Representations Predict Human Behavior in Naturalistic Learning Tasks

Jun 15, 2023

Abstract:Humans possess the ability to identify and generalize relevant features of natural objects, which aids them in various situations. To investigate this phenomenon and determine the most effective representations for predicting human behavior, we conducted two experiments involving category learning and reward learning. Our experiments used realistic images as stimuli, and participants were tasked with making accurate decisions based on novel stimuli for all trials, thereby necessitating generalization. In both tasks, the underlying rules were generated as simple linear functions using stimulus dimensions extracted from human similarity judgments. Notably, participants successfully identified the relevant stimulus features within a few trials, demonstrating effective generalization. We performed an extensive model comparison, evaluating the trial-by-trial predictive accuracy of diverse deep learning models' representations of human choices. Intriguingly, representations from models trained on both text and image data consistently outperformed models trained solely on images, even surpassing models using the features that generated the task itself. These findings suggest that language-aligned visual representations possess sufficient richness to describe human generalization in naturalistic settings and emphasize the role of language in shaping human cognition.

Turning large language models into cognitive models

Jun 06, 2023Abstract:Large language models are powerful systems that excel at many tasks, ranging from translation to mathematical reasoning. Yet, at the same time, these models often show unhuman-like characteristics. In the present paper, we address this gap and ask whether large language models can be turned into cognitive models. We find that -- after finetuning them on data from psychological experiments -- these models offer accurate representations of human behavior, even outperforming traditional cognitive models in two decision-making domains. In addition, we show that their representations contain the information necessary to model behavior on the level of individual subjects. Finally, we demonstrate that finetuning on multiple tasks enables large language models to predict human behavior in a previously unseen task. Taken together, these results suggest that large, pre-trained models can be adapted to become generalist cognitive models, thereby opening up new research directions that could transform cognitive psychology and the behavioral sciences as a whole.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge