Hyowon Gweon

BEHAVIOR-1K: A Human-Centered, Embodied AI Benchmark with 1,000 Everyday Activities and Realistic Simulation

Mar 14, 2024

Abstract:We present BEHAVIOR-1K, a comprehensive simulation benchmark for human-centered robotics. BEHAVIOR-1K includes two components, guided and motivated by the results of an extensive survey on "what do you want robots to do for you?". The first is the definition of 1,000 everyday activities, grounded in 50 scenes (houses, gardens, restaurants, offices, etc.) with more than 9,000 objects annotated with rich physical and semantic properties. The second is OMNIGIBSON, a novel simulation environment that supports these activities via realistic physics simulation and rendering of rigid bodies, deformable bodies, and liquids. Our experiments indicate that the activities in BEHAVIOR-1K are long-horizon and dependent on complex manipulation skills, both of which remain a challenge for even state-of-the-art robot learning solutions. To calibrate the simulation-to-reality gap of BEHAVIOR-1K, we provide an initial study on transferring solutions learned with a mobile manipulator in a simulated apartment to its real-world counterpart. We hope that BEHAVIOR-1K's human-grounded nature, diversity, and realism make it valuable for embodied AI and robot learning research. Project website: https://behavior.stanford.edu.

iGibson 2.0: Object-Centric Simulation for Robot Learning of Everyday Household Tasks

Aug 10, 2021

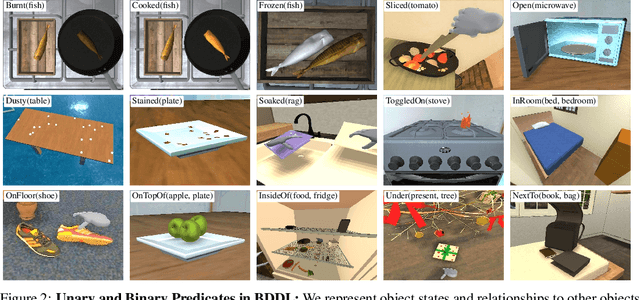

Abstract:Recent research in embodied AI has been boosted by the use of simulation environments to develop and train robot learning approaches. However, the use of simulation has skewed the attention to tasks that only require what robotics simulators can simulate: motion and physical contact. We present iGibson 2.0, an open-source simulation environment that supports the simulation of a more diverse set of household tasks through three key innovations. First, iGibson 2.0 supports object states, including temperature, wetness level, cleanliness level, and toggled and sliced states, necessary to cover a wider range of tasks. Second, iGibson 2.0 implements a set of predicate logic functions that map the simulator states to logic states like Cooked or Soaked. Additionally, given a logic state, iGibson 2.0 can sample valid physical states that satisfy it. This functionality can generate potentially infinite instances of tasks with minimal effort from the users. The sampling mechanism allows our scenes to be more densely populated with small objects in semantically meaningful locations. Third, iGibson 2.0 includes a virtual reality (VR) interface to immerse humans in its scenes to collect demonstrations. As a result, we can collect demonstrations from humans on these new types of tasks, and use them for imitation learning. We evaluate the new capabilities of iGibson 2.0 to enable robot learning of novel tasks, in the hope of demonstrating the potential of this new simulator to support new research in embodied AI. iGibson 2.0 and its new dataset will be publicly available at http://svl.stanford.edu/igibson/.

BEHAVIOR: Benchmark for Everyday Household Activities in Virtual, Interactive, and Ecological Environments

Aug 06, 2021

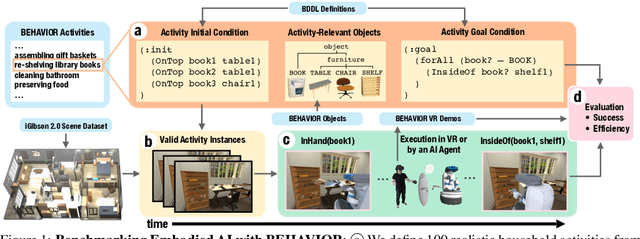

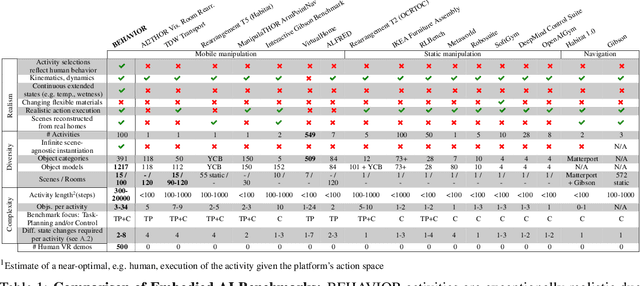

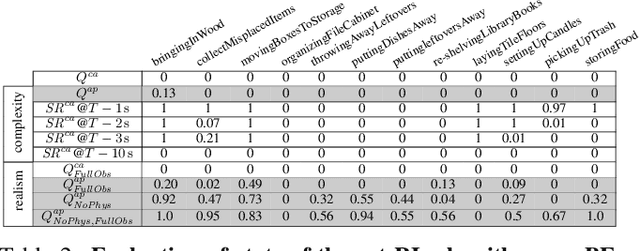

Abstract:We introduce BEHAVIOR, a benchmark for embodied AI with 100 activities in simulation, spanning a range of everyday household chores such as cleaning, maintenance, and food preparation. These activities are designed to be realistic, diverse, and complex, aiming to reproduce the challenges that agents must face in the real world. Building such a benchmark poses three fundamental difficulties for each activity: definition (it can differ by time, place, or person), instantiation in a simulator, and evaluation. BEHAVIOR addresses these with three innovations. First, we propose an object-centric, predicate logic-based description language for expressing an activity's initial and goal conditions, enabling generation of diverse instances for any activity. Second, we identify the simulator-agnostic features required by an underlying environment to support BEHAVIOR, and demonstrate its realization in one such simulator. Third, we introduce a set of metrics to measure task progress and efficiency, absolute and relative to human demonstrators. We include 500 human demonstrations in virtual reality (VR) to serve as the human ground truth. Our experiments demonstrate that even state of the art embodied AI solutions struggle with the level of realism, diversity, and complexity imposed by the activities in our benchmark. We make BEHAVIOR publicly available at behavior.stanford.edu to facilitate and calibrate the development of new embodied AI solutions.

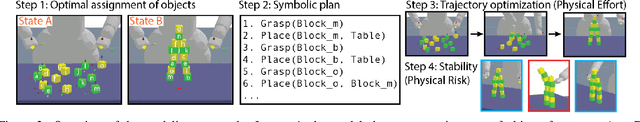

Explaining intuitive difficulty judgments by modeling physical effort and risk

May 14, 2019

Abstract:The ability to estimate task difficulty is critical for many real-world decisions such as setting appropriate goals for ourselves or appreciating others' accomplishments. Here we give a computational account of how humans judge the difficulty of a range of physical construction tasks (e.g., moving 10 loose blocks from their initial configuration to their target configuration, such as a vertical tower) by quantifying two key factors that influence construction difficulty: physical effort and physical risk. Physical effort captures the minimal work needed to transport all objects to their final positions, and is computed using a hybrid task-and-motion planner. Physical risk corresponds to stability of the structure, and is computed using noisy physics simulations to capture the costs for precision (e.g., attention, coordination, fine motor movements) required for success. We show that the full effort-risk model captures human estimates of difficulty and construction time better than either component alone.

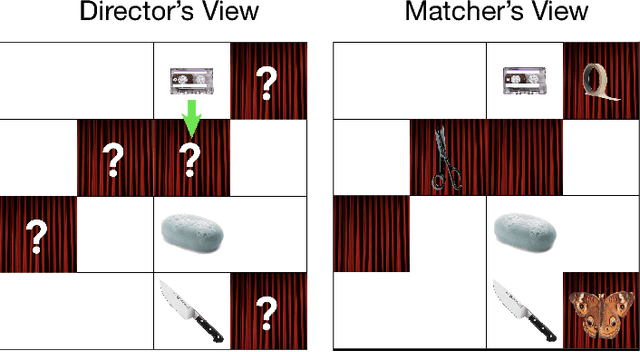

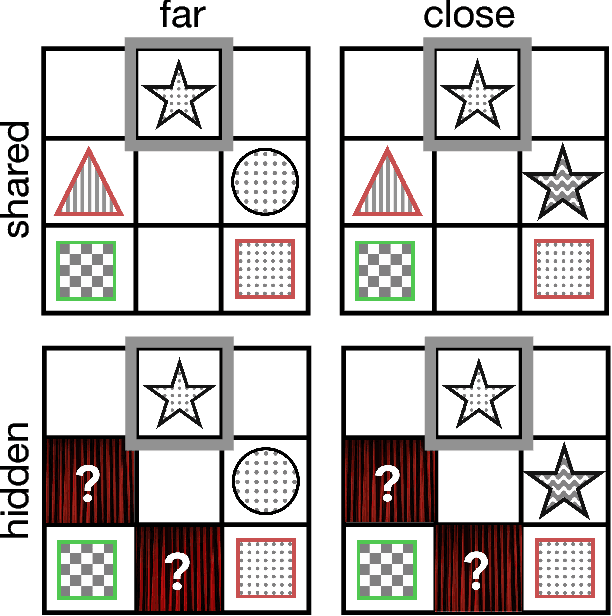

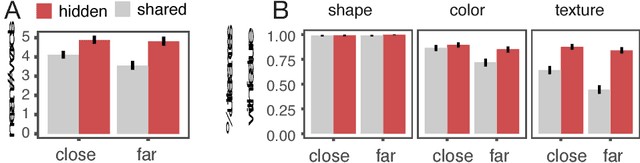

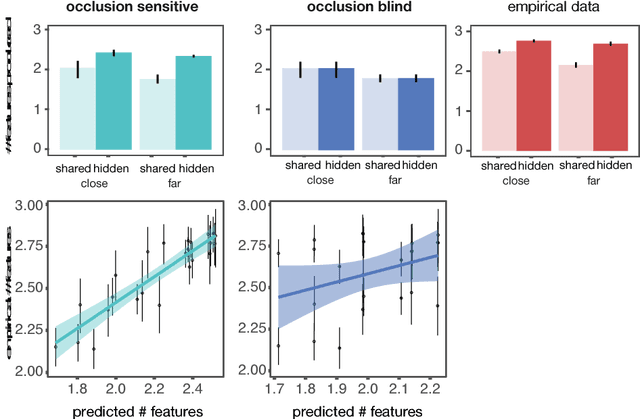

Speakers account for asymmetries in visual perspective so listeners don't have to

Oct 22, 2018

Abstract:Debates over adults' theory of mind use have been fueled by surprising failures of visual perspective-taking in simple communicative tasks. Motivated by recent computational models of context-sensitive language use, we reconsider the evidence in light of the nuanced Gricean pragmatics of these tasks: the differential informativity expected of a speaker depending on the context. In particular, when speakers are faced with asymmetries in visual access---when it is clear that additional objects are in their partner's view but not their own---our model predicts that they ought to adjust their utterances to be more informative. In Exp. 1, we explicitly manipulated the presence or absence of occlusions and found that speakers systematically produced longer, more specific referring expressions than required given their own view. In Exp. 2, we compare the scripted utterances used by confederates in prior work with those produced by unscripted speakers in the same task. We find that confederates are systematically less informative than would be expected, leading to more listener errors. In addition to demonstrating a sophisticated form of speaker perspective-taking, these results suggest a resource-rational explanation for why listeners may sometimes neglect to consider visual perspective: it may be justified by adaptive Gricean expectations about the likely division of joint cognitive effort.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge