Speakers account for asymmetries in visual perspective so listeners don't have to

Paper and Code

Oct 22, 2018

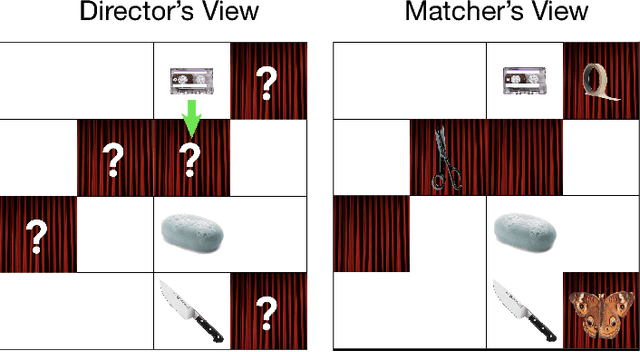

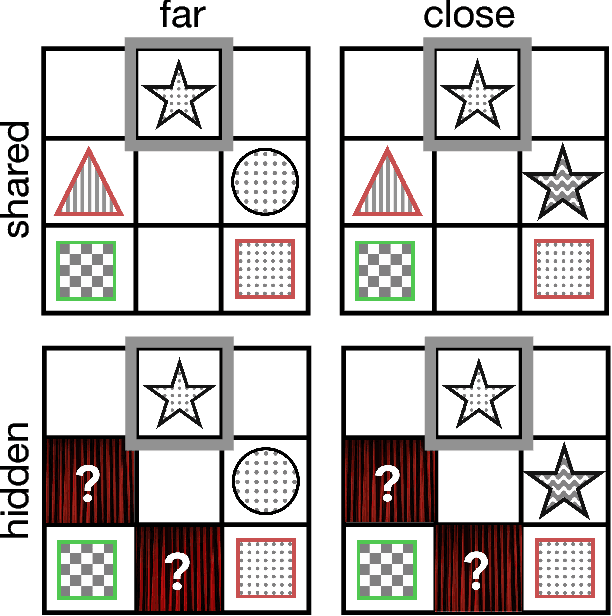

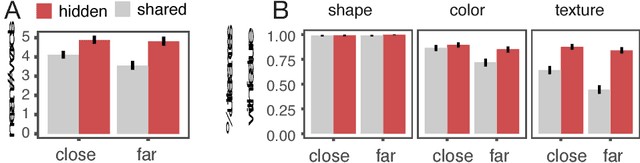

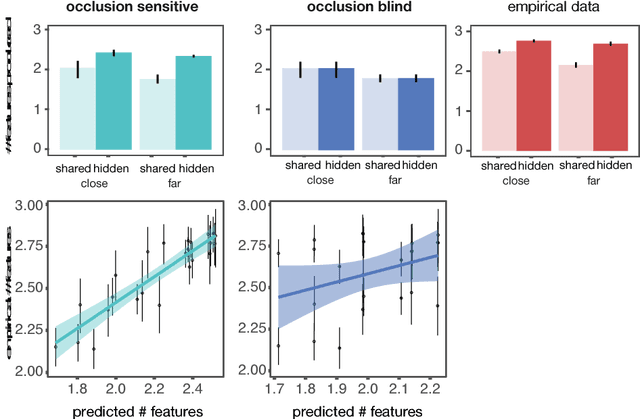

Debates over adults' theory of mind use have been fueled by surprising failures of visual perspective-taking in simple communicative tasks. Motivated by recent computational models of context-sensitive language use, we reconsider the evidence in light of the nuanced Gricean pragmatics of these tasks: the differential informativity expected of a speaker depending on the context. In particular, when speakers are faced with asymmetries in visual access---when it is clear that additional objects are in their partner's view but not their own---our model predicts that they ought to adjust their utterances to be more informative. In Exp. 1, we explicitly manipulated the presence or absence of occlusions and found that speakers systematically produced longer, more specific referring expressions than required given their own view. In Exp. 2, we compare the scripted utterances used by confederates in prior work with those produced by unscripted speakers in the same task. We find that confederates are systematically less informative than would be expected, leading to more listener errors. In addition to demonstrating a sophisticated form of speaker perspective-taking, these results suggest a resource-rational explanation for why listeners may sometimes neglect to consider visual perspective: it may be justified by adaptive Gricean expectations about the likely division of joint cognitive effort.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge