Timnit Gebru

A Human Rights-Based Approach to Responsible AI

Oct 06, 2022

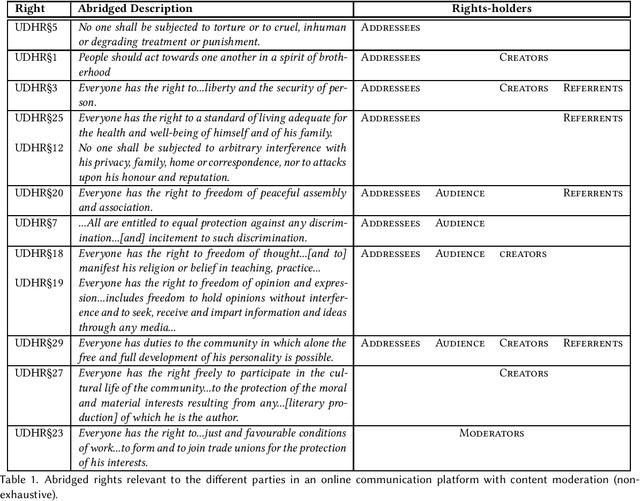

Abstract:Research on fairness, accountability, transparency and ethics of AI-based interventions in society has gained much-needed momentum in recent years. However it lacks an explicit alignment with a set of normative values and principles that guide this research and interventions. Rather, an implicit consensus is often assumed to hold for the values we impart into our models - something that is at odds with the pluralistic world we live in. In this paper, we put forth the doctrine of universal human rights as a set of globally salient and cross-culturally recognized set of values that can serve as a grounding framework for explicit value alignment in responsible AI - and discuss its efficacy as a framework for civil society partnership and participation. We argue that a human rights framework orients the research in this space away from the machines and the risks of their biases, and towards humans and the risks to their rights, essentially helping to center the conversation around who is harmed, what harms they face, and how those harms may be mitigated.

Diversity and Inclusion Metrics in Subset Selection

Feb 09, 2020

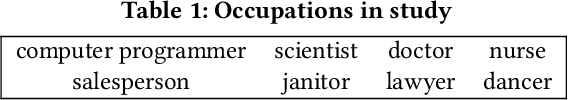

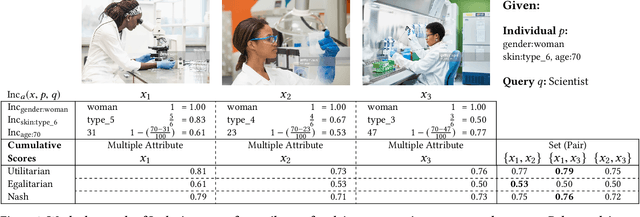

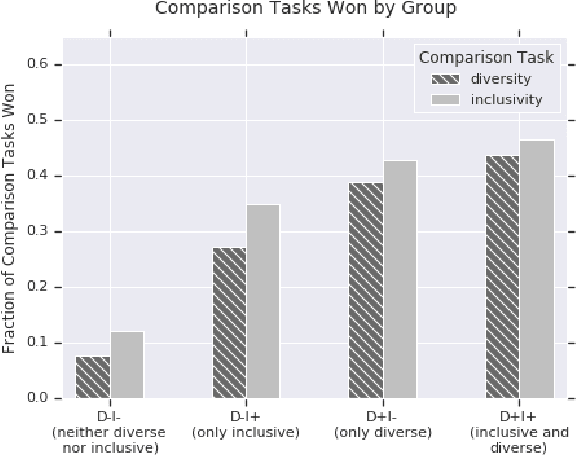

Abstract:The ethical concept of fairness has recently been applied in machine learning (ML) settings to describe a wide range of constraints and objectives. When considering the relevance of ethical concepts to subset selection problems, the concepts of diversity and inclusion are additionally applicable in order to create outputs that account for social power and access differentials. We introduce metrics based on these concepts, which can be applied together, separately, and in tandem with additional fairness constraints. Results from human subject experiments lend support to the proposed criteria. Social choice methods can additionally be leveraged to aggregate and choose preferable sets, and we detail how these may be applied.

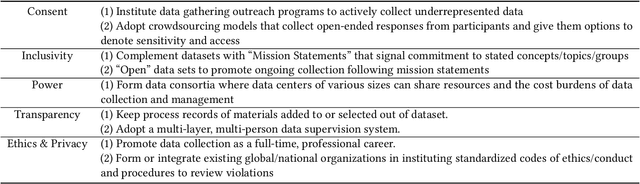

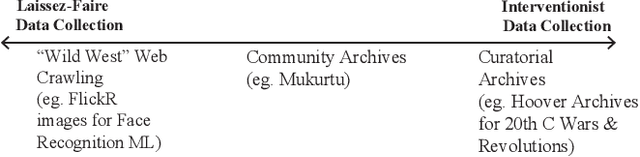

Lessons from Archives: Strategies for Collecting Sociocultural Data in Machine Learning

Dec 22, 2019

Abstract:A growing body of work shows that many problems in fairness, accountability, transparency, and ethics in machine learning systems are rooted in decisions surrounding the data collection and annotation process. In spite of its fundamental nature however, data collection remains an overlooked part of the machine learning (ML) pipeline. In this paper, we argue that a new specialization should be formed within ML that is focused on methodologies for data collection and annotation: efforts that require institutional frameworks and procedures. Specifically for sociocultural data, parallels can be drawn from archives and libraries. Archives are the longest standing communal effort to gather human information and archive scholars have already developed the language and procedures to address and discuss many challenges pertaining to data collection such as consent, power, inclusivity, transparency, and ethics & privacy. We discuss these five key approaches in document collection practices in archives that can inform data collection in sociocultural ML. By showing data collection practices from another field, we encourage ML research to be more cognizant and systematic in data collection and draw from interdisciplinary expertise.

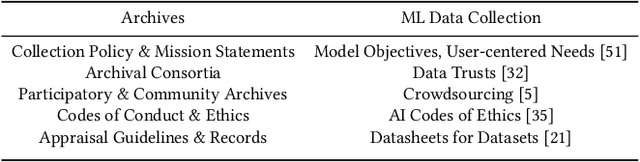

Oxford Handbook on AI Ethics Book Chapter on Race and Gender

Aug 08, 2019Abstract:From massive face-recognition-based surveillance and machine-learning-based decision systems predicting crime recidivism rates, to the move towards automated health diagnostic systems, artificial intelligence (AI) is being used in scenarios that have serious consequences in people's lives. However, this rapid permeation of AI into society has not been accompanied by a thorough investigation of the sociopolitical issues that cause certain groups of people to be harmed rather than advantaged by it. For instance, recent studies have shown that commercial face recognition systems have much higher error rates for dark skinned women while having minimal errors on light skinned men. A 2016 ProPublica investigation uncovered that machine learning based tools that assess crime recidivism rates in the US are biased against African Americans. Other studies show that natural language processing tools trained on newspapers exhibit societal biases (e.g. finishing the analogy "Man is to computer programmer as woman is to X" by homemaker). At the same time, books such as Weapons of Math Destruction and Automated Inequality detail how people in lower socioeconomic classes in the US are subjected to more automated decision making tools than those who are in the upper class. Thus, these tools are most often used on people towards whom they exhibit the most bias. While many technical solutions have been proposed to alleviate bias in machine learning systems, we have to take a holistic and multifaceted approach. This includes standardization bodies determining what types of systems can be used in which scenarios, making sure that automated decision tools are created by people from diverse backgrounds, and understanding the historical and political factors that disadvantage certain groups who are subjected to these tools.

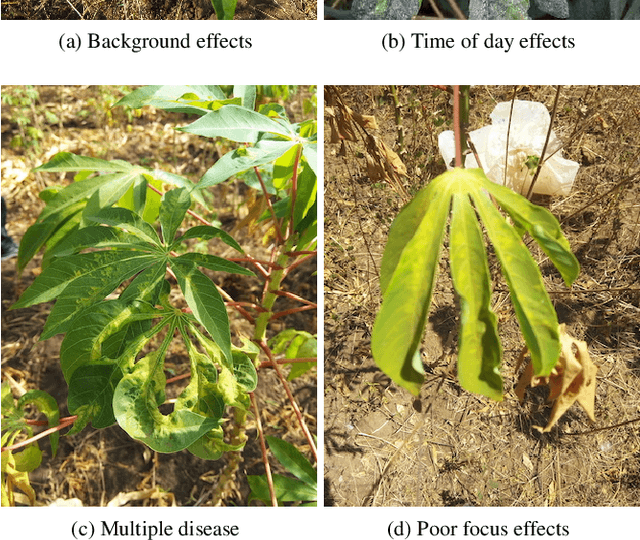

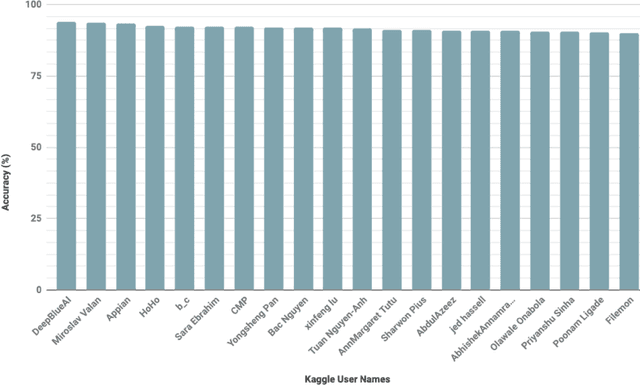

iCassava 2019Fine-Grained Visual Categorization Challenge

Aug 08, 2019

Abstract:Viral diseases are major sources of poor yields for cassava, the 2nd largest provider of carbohydrates in Africa.At least 80% of small-holder farmer households in Sub-Saharan Africa grow cassava. Since many of these farmers have smart phones, they can easily obtain photos of dis-eased and healthy cassava leaves in their farms, allowing the opportunity to use computer vision techniques to monitor the disease type and severity and increase yields. How-ever, annotating these images is extremely difficult as ex-perts who are able to distinguish between highly similar dis-eases need to be employed. We provide a dataset of labeled and unlabeled cassava leaves and formulate a Kaggle challenge to encourage participants to improve the performance of their algorithms using semi-supervised approaches. This paper describes our dataset and challenge which is part of the Fine-Grained Visual Categorization workshop at CVPR2019.

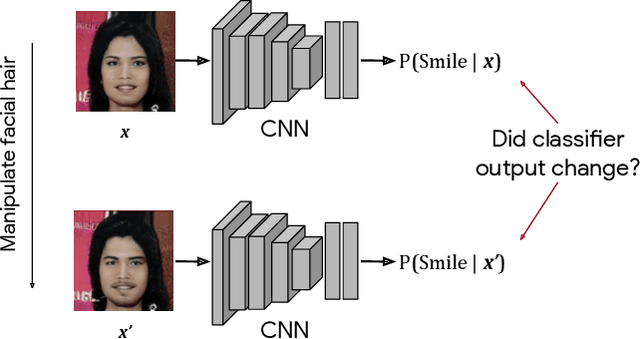

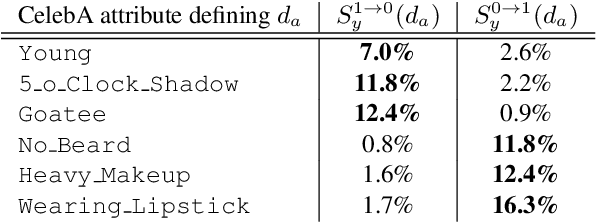

Detecting Bias with Generative Counterfactual Face Attribute Augmentation

Jun 18, 2019

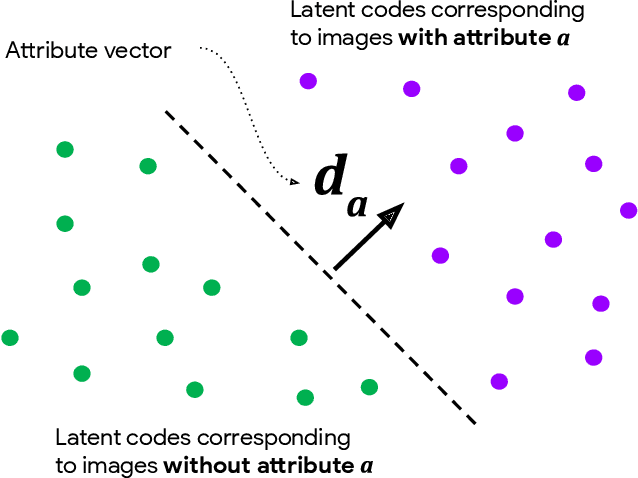

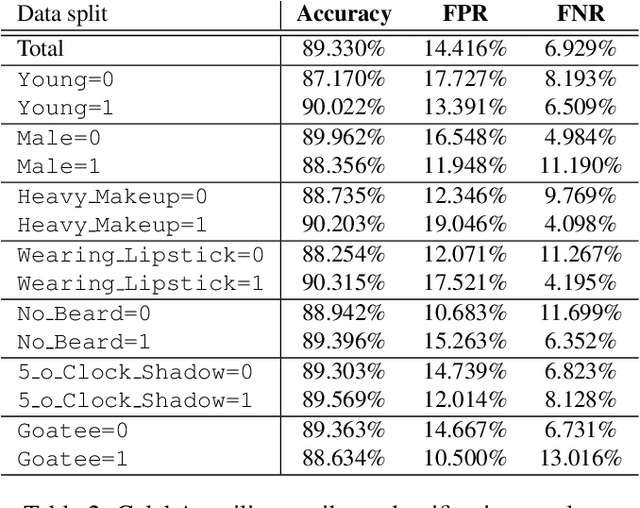

Abstract:We introduce a simple framework for identifying biases of a smiling attribute classifier. Our method poses counterfactual questions of the form: how would the prediction change if this face characteristic had been different? We leverage recent advances in generative adversarial networks to build a realistic generative model of face images that affords controlled manipulation of specific image characteristics. We introduce a set of metrics that measure the effect of manipulating a specific property of an image on the output of a trained classifier. Empirically, we identify several different factors of variation that affect the predictions of a smiling classifier trained on CelebA.

Datasheets for Datasets

Jul 09, 2018

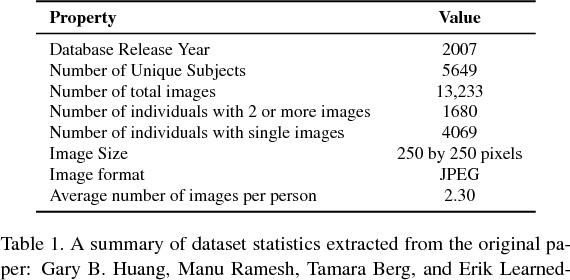

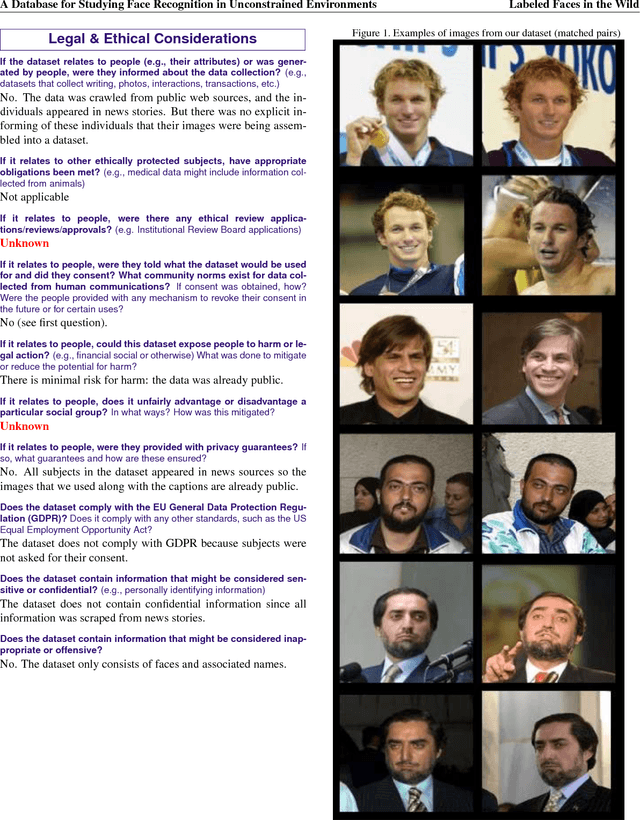

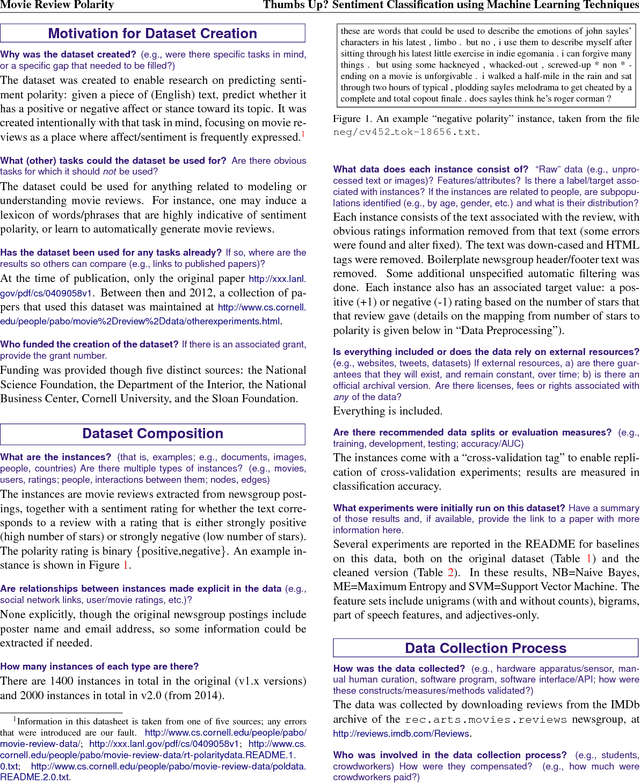

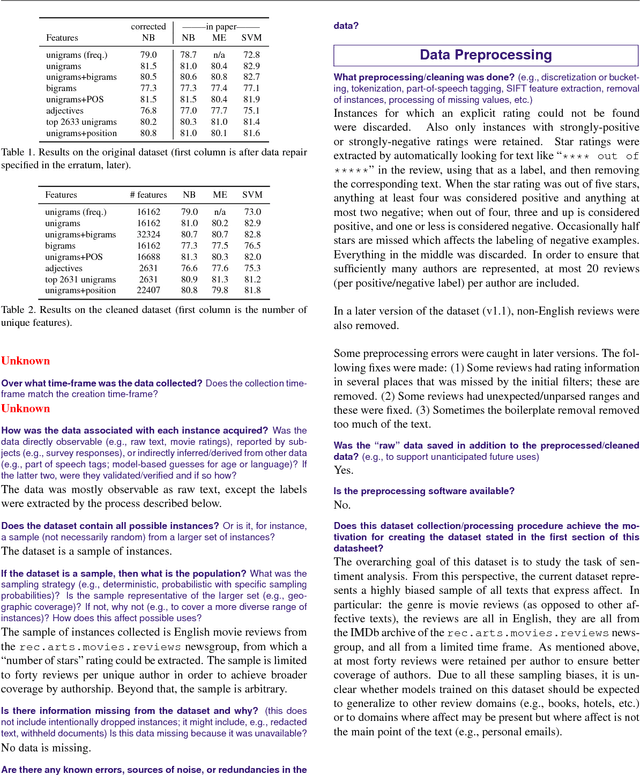

Abstract:Currently there is no standard way to identify how a dataset was created, and what characteristics, motivations, and potential skews it represents. To begin to address this issue, we propose the concept of a datasheet for datasets, a short document to accompany public datasets, commercial APIs, and pretrained models. The goal of this proposal is to enable better communication between dataset creators and users, and help the AI community move toward greater transparency and accountability. By analogy, in computer hardware, it has become industry standard to accompany everything from the simplest components (e.g., resistors), to the most complex microprocessor chips, with datasheets detailing standard operating characteristics, test results, recommended usage, and other information. We outline some of the questions a datasheet for datasets should answer. These questions focus on when, where, and how the training data was gathered, its recommended use cases, and, in the case of human-centric datasets, information regarding the subjects' demographics and consent as applicable. We develop prototypes of datasheets for two well-known datasets: Labeled Faces in The Wild and the Pang \& Lee Polarity Dataset.

Scalable Annotation of Fine-Grained Categories Without Experts

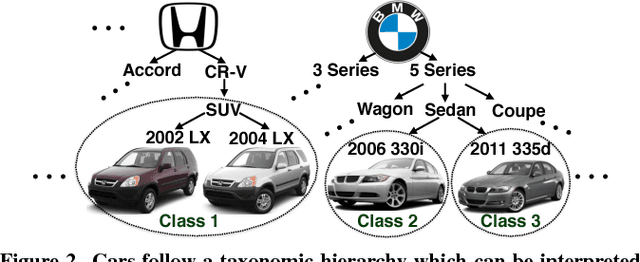

Sep 07, 2017

Abstract:We present a crowdsourcing workflow to collect image annotations for visually similar synthetic categories without requiring experts. In animals, there is a direct link between taxonomy and visual similarity: e.g. a collie (type of dog) looks more similar to other collies (e.g. smooth collie) than a greyhound (another type of dog). However, in synthetic categories such as cars, objects with similar taxonomy can have very different appearance: e.g. a 2011 Ford F-150 Supercrew-HD looks the same as a 2011 Ford F-150 Supercrew-LL but very different from a 2011 Ford F-150 Supercrew-SVT. We introduce a graph based crowdsourcing algorithm to automatically group visually indistinguishable objects together. Using our workflow, we label 712,430 images by ~1,000 Amazon Mechanical Turk workers; resulting in the largest fine-grained visual dataset reported to date with 2,657 categories of cars annotated at 1/20th the cost of hiring experts.

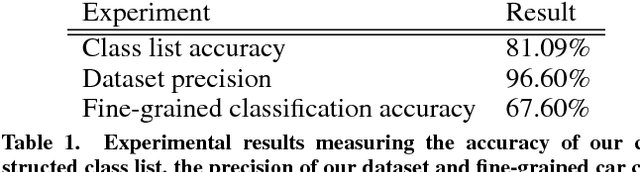

Fine-Grained Car Detection for Visual Census Estimation

Sep 07, 2017

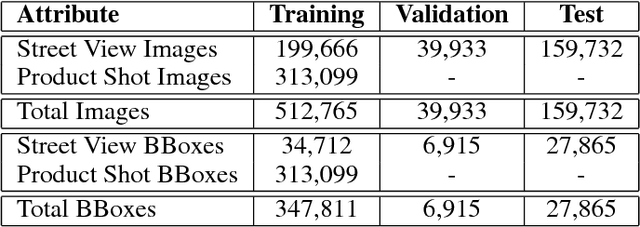

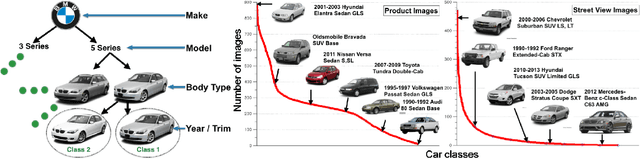

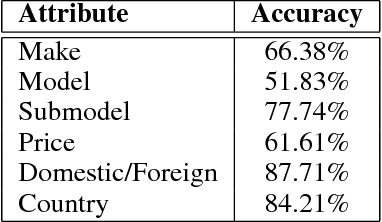

Abstract:Targeted socioeconomic policies require an accurate understanding of a country's demographic makeup. To that end, the United States spends more than 1 billion dollars a year gathering census data such as race, gender, education, occupation and unemployment rates. Compared to the traditional method of collecting surveys across many years which is costly and labor intensive, data-driven, machine learning driven approaches are cheaper and faster--with the potential ability to detect trends in close to real time. In this work, we leverage the ubiquity of Google Street View images and develop a computer vision pipeline to predict income, per capita carbon emission, crime rates and other city attributes from a single source of publicly available visual data. We first detect cars in 50 million images across 200 of the largest US cities and train a model to predict demographic attributes using the detected cars. To facilitate our work, we have collected the largest and most challenging fine-grained dataset reported to date consisting of over 2600 classes of cars comprised of images from Google Street View and other web sources, classified by car experts to account for even the most subtle of visual differences. We use this data to construct the largest scale fine-grained detection system reported to date. Our prediction results correlate well with ground truth income data (r=0.82), Massachusetts department of vehicle registration, and sources investigating crime rates, income segregation, per capita carbon emission, and other market research. Finally, we learn interesting relationships between cars and neighborhoods allowing us to perform the first large scale sociological analysis of cities using computer vision techniques.

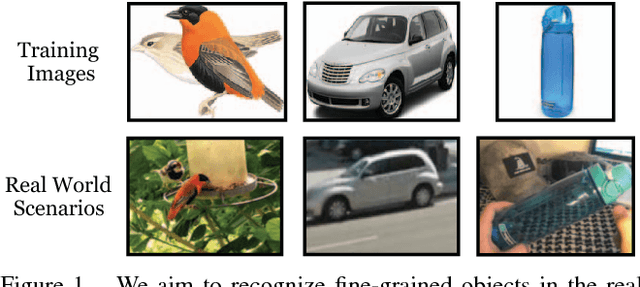

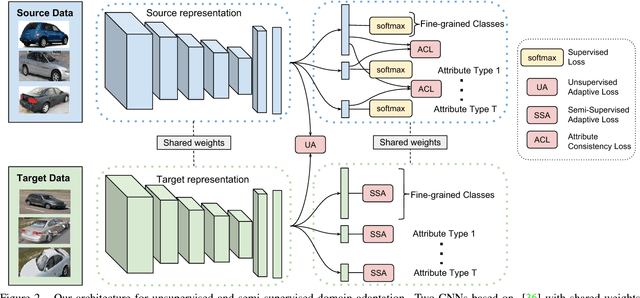

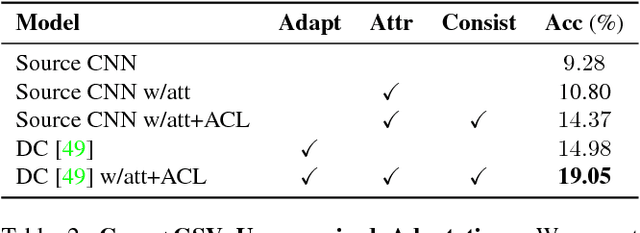

Fine-grained Recognition in the Wild: A Multi-Task Domain Adaptation Approach

Sep 07, 2017

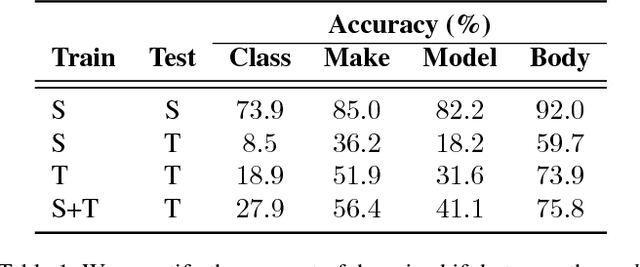

Abstract:While fine-grained object recognition is an important problem in computer vision, current models are unlikely to accurately classify objects in the wild. These fully supervised models need additional annotated images to classify objects in every new scenario, a task that is infeasible. However, sources such as e-commerce websites and field guides provide annotated images for many classes. In this work, we study fine-grained domain adaptation as a step towards overcoming the dataset shift between easily acquired annotated images and the real world. Adaptation has not been studied in the fine-grained setting where annotations such as attributes could be used to increase performance. Our work uses an attribute based multi-task adaptation loss to increase accuracy from a baseline of 4.1% to 19.1% in the semi-supervised adaptation case. Prior do- main adaptation works have been benchmarked on small datasets such as [46] with a total of 795 images for some domains, or simplistic datasets such as [41] consisting of digits. We perform experiments on a subset of a new challenging fine-grained dataset consisting of 1,095,021 images of 2, 657 car categories drawn from e-commerce web- sites and Google Street View.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge