Ethan Gotlieb Wilcox

From Linear Input to Hierarchical Structure: Function Words as Statistical Cues for Language Learning

Jan 29, 2026Abstract:What statistical conditions support learning hierarchical structure from linear input? In this paper, we address this question by focusing on the statistical distribution of function words. Function words have long been argued to play a crucial role in language acquisition due to their distinctive distributional properties, including high frequency, reliable association with syntactic structure, and alignment with phrase boundaries. We use cross-linguistic corpus analysis to first establish that all three properties are present across 186 studied languages. Next, we use a combination of counterfactual language modeling and ablation experiments to show that language variants preserving all three properties are more easily acquired by neural learners, with frequency and structural association contributing more strongly than boundary alignment. Follow-up probing and ablation analyses further reveal that different learning conditions lead to systematically different reliance on function words, indicating that similar performance can arise from distinct internal mechanisms.

Using Information Theory to Characterize Prosodic Typology: The Case of Tone, Pitch-Accent and Stress-Accent

May 12, 2025Abstract:This paper argues that the relationship between lexical identity and prosody -- one well-studied parameter of linguistic variation -- can be characterized using information theory. We predict that languages that use prosody to make lexical distinctions should exhibit a higher mutual information between word identity and prosody, compared to languages that don't. We test this hypothesis in the domain of pitch, which is used to make lexical distinctions in tonal languages, like Cantonese. We use a dataset of speakers reading sentences aloud in ten languages across five language families to estimate the mutual information between the text and their pitch curves. We find that, across languages, pitch curves display similar amounts of entropy. However, these curves are easier to predict given their associated text in the tonal languages, compared to pitch- and stress-accent languages, and thus the mutual information is higher in these languages, supporting our hypothesis. Our results support perspectives that view linguistic typology as gradient, rather than categorical.

Looking forward: Linguistic theory and methods

Feb 25, 2025Abstract:This chapter examines current developments in linguistic theory and methods, focusing on the increasing integration of computational, cognitive, and evolutionary perspectives. We highlight four major themes shaping contemporary linguistics: (1) the explicit testing of hypotheses about symbolic representation, such as efficiency, locality, and conceptual semantic grounding; (2) the impact of artificial neural networks on theoretical debates and linguistic analysis; (3) the importance of intersubjectivity in linguistic theory; and (4) the growth of evolutionary linguistics. By connecting linguistics with computer science, psychology, neuroscience, and biology, we provide a forward-looking perspective on the changing landscape of linguistic research.

Findings of the Second BabyLM Challenge: Sample-Efficient Pretraining on Developmentally Plausible Corpora

Dec 06, 2024Abstract:The BabyLM Challenge is a community effort to close the data-efficiency gap between human and computational language learners. Participants compete to optimize language model training on a fixed language data budget of 100 million words or less. This year, we released improved text corpora, as well as a vision-and-language corpus to facilitate research into cognitively plausible vision language models. Submissions were compared on evaluation tasks targeting grammatical ability, (visual) question answering, pragmatic abilities, and grounding, among other abilities. Participants could submit to a 10M-word text-only track, a 100M-word text-only track, and/or a 100M-word and image multimodal track. From 31 submissions employing diverse methods, a hybrid causal-masked language model architecture outperformed other approaches. No submissions outperformed the baselines in the multimodal track. In follow-up analyses, we found a strong relationship between training FLOPs and average performance across tasks, and that the best-performing submissions proposed changes to the training data, training objective, and model architecture. This year's BabyLM Challenge shows that there is still significant room for innovation in this setting, in particular for image-text modeling, but community-driven research can yield actionable insights about effective strategies for small-scale language modeling.

Reverse-Engineering the Reader

Oct 16, 2024Abstract:Numerous previous studies have sought to determine to what extent language models, pretrained on natural language text, can serve as useful models of human cognition. In this paper, we are interested in the opposite question: whether we can directly optimize a language model to be a useful cognitive model by aligning it to human psychometric data. To achieve this, we introduce a novel alignment technique in which we fine-tune a language model to implicitly optimize the parameters of a linear regressor that directly predicts humans' reading times of in-context linguistic units, e.g., phonemes, morphemes, or words, using surprisal estimates derived from the language model. Using words as a test case, we evaluate our technique across multiple model sizes and datasets and find that it improves language models' psychometric predictive power. However, we find an inverse relationship between psychometric power and a model's performance on downstream NLP tasks as well as its perplexity on held-out test data. While this latter trend has been observed before (Oh et al., 2022; Shain et al., 2024), we are the first to induce it by manipulating a model's alignment to psychometric data.

On the Role of Context in Reading Time Prediction

Sep 12, 2024

Abstract:We present a new perspective on how readers integrate context during real-time language comprehension. Our proposals build on surprisal theory, which posits that the processing effort of a linguistic unit (e.g., a word) is an affine function of its in-context information content. We first observe that surprisal is only one out of many potential ways that a contextual predictor can be derived from a language model. Another one is the pointwise mutual information (PMI) between a unit and its context, which turns out to yield the same predictive power as surprisal when controlling for unigram frequency. Moreover, both PMI and surprisal are correlated with frequency. This means that neither PMI nor surprisal contains information about context alone. In response to this, we propose a technique where we project surprisal onto the orthogonal complement of frequency, yielding a new contextual predictor that is uncorrelated with frequency. Our experiments show that the proportion of variance in reading times explained by context is a lot smaller when context is represented by the orthogonalized predictor. From an interpretability standpoint, this indicates that previous studies may have overstated the role that context has in predicting reading times.

Revisiting the Optimality of Word Lengths

Dec 06, 2023

Abstract:Zipf (1935) posited that wordforms are optimized to minimize utterances' communicative costs. Under the assumption that cost is given by an utterance's length, he supported this claim by showing that words' lengths are inversely correlated with their frequencies. Communicative cost, however, can be operationalized in different ways. Piantadosi et al. (2011) claim that cost should be measured as the distance between an utterance's information rate and channel capacity, which we dub the channel capacity hypothesis (CCH) here. Following this logic, they then proposed that a word's length should be proportional to the expected value of its surprisal (negative log-probability in context). In this work, we show that Piantadosi et al.'s derivation does not minimize CCH's cost, but rather a lower bound, which we term CCH-lower. We propose a novel derivation, suggesting an improved way to minimize CCH's cost. Under this method, we find that a language's word lengths should instead be proportional to the surprisal's expectation plus its variance-to-mean ratio. Experimentally, we compare these three communicative cost functions: Zipf's, CCH-lower , and CCH. Across 13 languages and several experimental settings, we find that length is better predicted by frequency than either of the other hypotheses. In fact, when surprisal's expectation, or expectation plus variance-to-mean ratio, is estimated using better language models, it leads to worse word length predictions. We take these results as evidence that Zipf's longstanding hypothesis holds.

Testing the Predictions of Surprisal Theory in 11 Languages

Jul 10, 2023Abstract:A fundamental result in psycholinguistics is that less predictable words take a longer time to process. One theoretical explanation for this finding is Surprisal Theory (Hale, 2001; Levy, 2008), which quantifies a word's predictability as its surprisal, i.e. its negative log-probability given a context. While evidence supporting the predictions of Surprisal Theory have been replicated widely, most have focused on a very narrow slice of data: native English speakers reading English texts. Indeed, no comprehensive multilingual analysis exists. We address this gap in the current literature by investigating the relationship between surprisal and reading times in eleven different languages, distributed across five language families. Deriving estimates from language models trained on monolingual and multilingual corpora, we test three predictions associated with surprisal theory: (i) whether surprisal is predictive of reading times; (ii) whether expected surprisal, i.e. contextual entropy, is predictive of reading times; (iii) and whether the linking function between surprisal and reading times is linear. We find that all three predictions are borne out crosslinguistically. By focusing on a more diverse set of languages, we argue that these results offer the most robust link to-date between information theory and incremental language processing across languages.

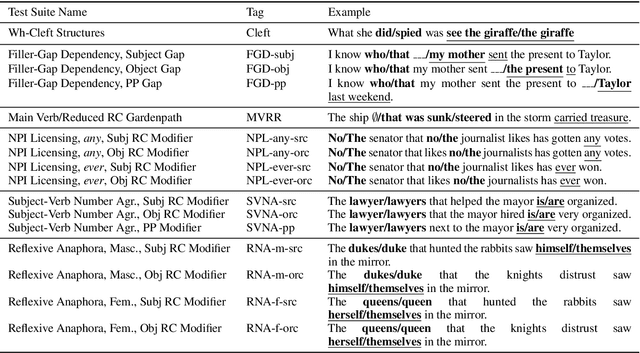

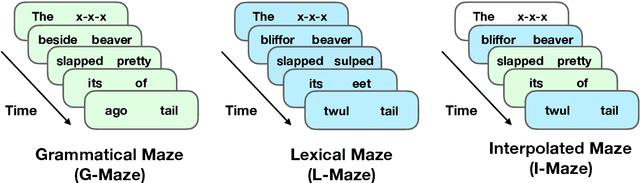

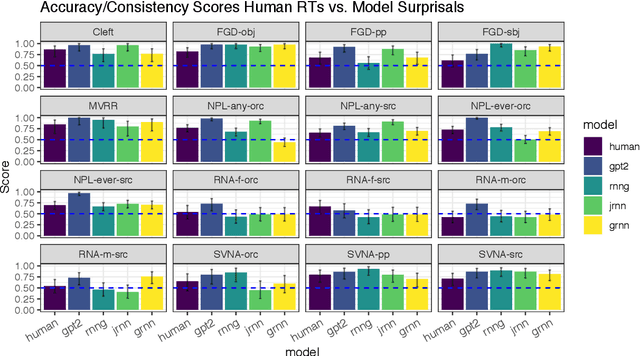

A Targeted Assessment of Incremental Processing in Neural LanguageModels and Humans

Jun 06, 2021

Abstract:We present a targeted, scaled-up comparison of incremental processing in humans and neural language models by collecting by-word reaction time data for sixteen different syntactic test suites across a range of structural phenomena. Human reaction time data comes from a novel online experimental paradigm called the Interpolated Maze task. We compare human reaction times to by-word probabilities for four contemporary language models, with different architectures and trained on a range of data set sizes. We find that across many phenomena, both humans and language models show increased processing difficulty in ungrammatical sentence regions with human and model `accuracy' scores (a la Marvin and Linzen(2018)) about equal. However, although language model outputs match humans in direction, we show that models systematically under-predict the difference in magnitude of incremental processing difficulty between grammatical and ungrammatical sentences. Specifically, when models encounter syntactic violations they fail to accurately predict the longer reaction times observed in the human data. These results call into question whether contemporary language models are approaching human-like performance for sensitivity to syntactic violations.

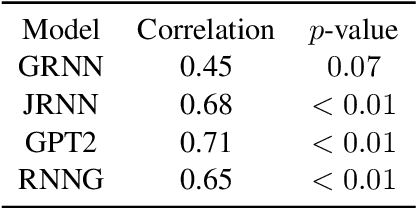

On the Predictive Power of Neural Language Models for Human Real-Time Comprehension Behavior

Jun 02, 2020

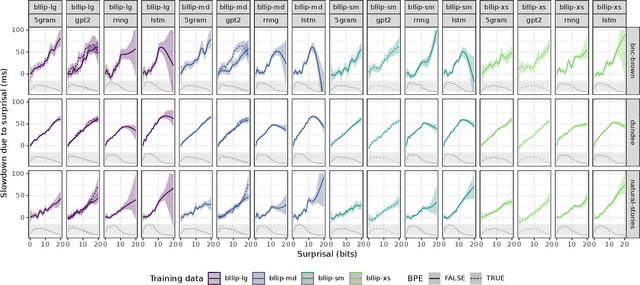

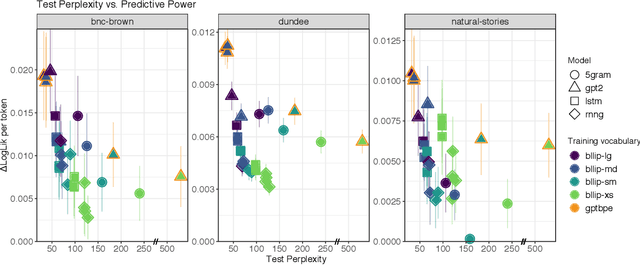

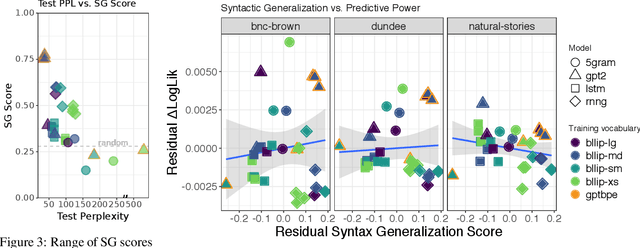

Abstract:Human reading behavior is tuned to the statistics of natural language: the time it takes human subjects to read a word can be predicted from estimates of the word's probability in context. However, it remains an open question what computational architecture best characterizes the expectations deployed in real time by humans that determine the behavioral signatures of reading. Here we test over two dozen models, independently manipulating computational architecture and training dataset size, on how well their next-word expectations predict human reading time behavior on naturalistic text corpora. We find that across model architectures and training dataset sizes the relationship between word log-probability and reading time is (near-)linear. We next evaluate how features of these models determine their psychometric predictive power, or ability to predict human reading behavior. In general, the better a model's next-word expectations, the better its psychometric predictive power. However, we find nontrivial differences across model architectures. For any given perplexity, deep Transformer models and n-gram models generally show superior psychometric predictive power over LSTM or structurally supervised neural models, especially for eye movement data. Finally, we compare models' psychometric predictive power to the depth of their syntactic knowledge, as measured by a battery of syntactic generalization tests developed using methods from controlled psycholinguistic experiments. Once perplexity is controlled for, we find no significant relationship between syntactic knowledge and predictive power. These results suggest that different approaches may be required to best model human real-time language comprehension behavior in naturalistic reading versus behavior for controlled linguistic materials designed for targeted probing of syntactic knowledge.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge