Kiran Garimella

Source Coverage and Citation Bias in LLM-based vs. Traditional Search Engines

Dec 10, 2025Abstract:LLM-based Search Engines (LLM-SEs) introduces a new paradigm for information seeking. Unlike Traditional Search Engines (TSEs) (e.g., Google), these systems summarize results, often providing limited citation transparency. The implications of this shift remain largely unexplored, yet raises key questions regarding trust and transparency. In this paper, we present a large-scale empirical study of LLM-SEs, analyzing 55,936 queries and the corresponding search results across six LLM-SEs and two TSEs. We confirm that LLM-SEs cites domain resources with greater diversity than TSEs. Indeed, 37% of domains are unique to LLM-SEs. However, certain risks still persist: LLM-SEs do not outperform TSEs in credibility, political neutrality and safety metrics. Finally, to understand the selection criteria of LLM-SEs, we perform a feature-based analysis to identify key factors influencing source choice. Our findings provide actionable insights for end users, website owners, and developers.

Listening Between the Lines: Decoding Podcast Narratives with Language Modeling

Nov 07, 2025

Abstract:Podcasts have become a central arena for shaping public opinion, making them a vital source for understanding contemporary discourse. Their typically unscripted, multi-themed, and conversational style offers a rich but complex form of data. To analyze how podcasts persuade and inform, we must examine their narrative structures -- specifically, the narrative frames they employ. The fluid and conversational nature of podcasts presents a significant challenge for automated analysis. We show that existing large language models, typically trained on more structured text such as news articles, struggle to capture the subtle cues that human listeners rely on to identify narrative frames. As a result, current approaches fall short of accurately analyzing podcast narratives at scale. To solve this, we develop and evaluate a fine-tuned BERT model that explicitly links narrative frames to specific entities mentioned in the conversation, effectively grounding the abstract frame in concrete details. Our approach then uses these granular frame labels and correlates them with high-level topics to reveal broader discourse trends. The primary contributions of this paper are: (i) a novel frame-labeling methodology that more closely aligns with human judgment for messy, conversational data, and (ii) a new analysis that uncovers the systematic relationship between what is being discussed (the topic) and how it is being presented (the frame), offering a more robust framework for studying influence in digital media.

Analyzing Patterns and Influence of Advertising in Print Newspapers

May 16, 2025Abstract:This paper investigates advertising practices in print newspapers across India using a novel data-driven approach. We develop a pipeline employing image processing and OCR techniques to extract articles and advertisements from digital versions of print newspapers with high accuracy. Applying this methodology to five popular newspapers that span multiple regions and three languages, English, Hindi, and Telugu, we assembled a dataset of more than 12,000 editions containing several hundred thousand advertisements. Collectively, these newspapers reach a readership of over 100 million people. Using this extensive dataset, we conduct a comprehensive analysis to answer key questions about print advertising: who advertises, what they advertise, when they advertise, where they place their ads, and how they advertise. Our findings reveal significant patterns, including the consistent level of print advertising over the past six years despite declining print circulation, the overrepresentation of company ads on prominent pages, and the disproportionate revenue contributed by government ads. Furthermore, we examine whether advertising in a newspaper influences the coverage an advertiser receives. Through regression analyses on coverage volume and sentiment, we find strong evidence supporting this hypothesis for corporate advertisers. The results indicate a clear trend where increased advertising correlates with more favorable and extensive media coverage, a relationship that remains robust over time and across different levels of advertiser popularity.

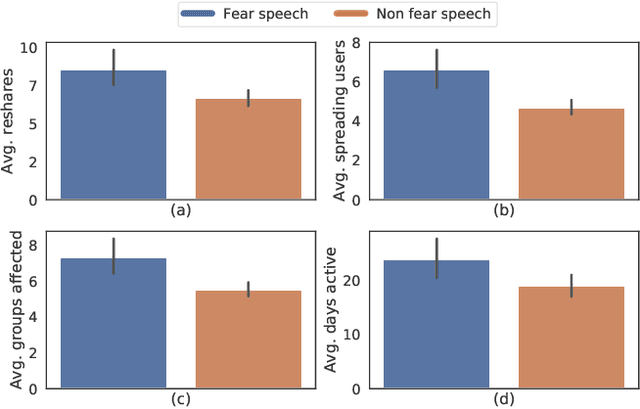

On the rise of fear speech in online social media

Mar 18, 2023

Abstract:Recently, social media platforms are heavily moderated to prevent the spread of online hate speech, which is usually fertile in toxic words and is directed toward an individual or a community. Owing to such heavy moderation, newer and more subtle techniques are being deployed. One of the most striking among these is fear speech. Fear speech, as the name suggests, attempts to incite fear about a target community. Although subtle, it might be highly effective, often pushing communities toward a physical conflict. Therefore, understanding their prevalence in social media is of paramount importance. This article presents a large-scale study to understand the prevalence of 400K fear speech and over 700K hate speech posts collected from Gab.com. Remarkably, users posting a large number of fear speech accrue more followers and occupy more central positions in social networks than users posting a large number of hate speech. They can also reach out to benign users more effectively than hate speech users through replies, reposts, and mentions. This connects to the fact that, unlike hate speech, fear speech has almost zero toxic content, making it look plausible. Moreover, while fear speech topics mostly portray a community as a perpetrator using a (fake) chain of argumentation, hate speech topics hurl direct multitarget insults, thus pointing to why general users could be more gullible to fear speech. Our findings transcend even to other platforms (Twitter and Facebook) and thus necessitate using sophisticated moderation policies and mass awareness to combat fear speech.

Diagnosing Web Data of ICTs to Provide Focused Assistance in Agricultural Adoptions

Oct 29, 2021

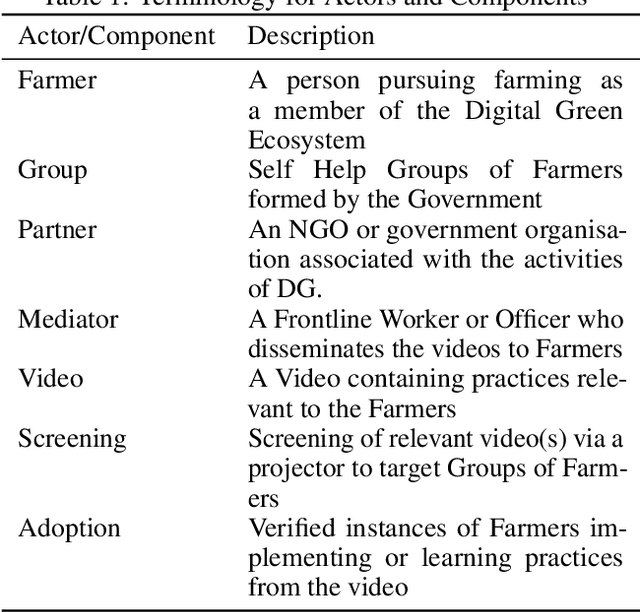

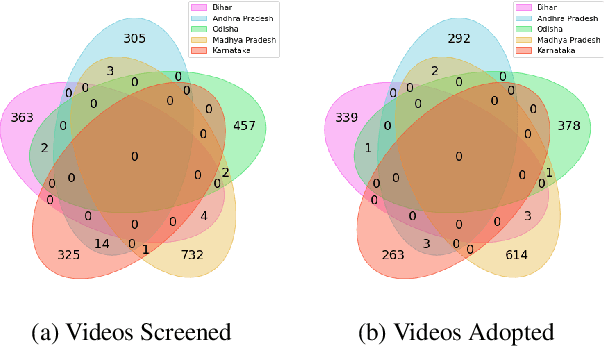

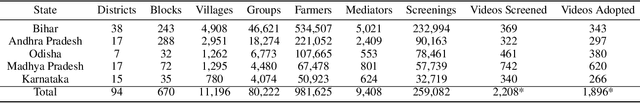

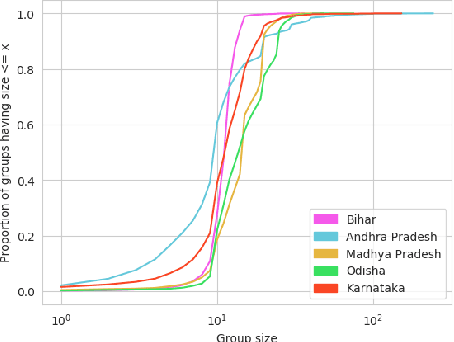

Abstract:The past decade has witnessed a rapid increase in technology ownership across rural areas of India, signifying the potential for ICT initiatives to empower rural households. In our work, we focus on the web infrastructure of one such ICT - Digital Green that started in 2008. Following a participatory approach for content production, Digital Green disseminates instructional agricultural videos to smallholder farmers via human mediators to improve the adoption of farming practices. Their web-based data tracker, CoCo, captures data related to these processes, storing the attendance and adoption logs of over 2.3 million farmers across three continents and twelve countries. Using this data, we model the components of the Digital Green ecosystem involving the past attendance-adoption behaviours of farmers, the content of the videos screened to them and their demographic features across five states in India. We use statistical tests to identify different factors which distinguish farmers with higher adoption rates to understand why they adopt more than others. Our research finds that farmers with higher adoption rates adopt videos of shorter duration and belong to smaller villages. The co-attendance and co-adoption networks of farmers indicate that they greatly benefit from past adopters of a video from their village and group when it comes to adopting practices from the same video. Following our analysis, we model the adoption of practices from a video as a prediction problem to identify and assist farmers who might face challenges in adoption in each of the five states. We experiment with different model architectures and achieve macro-f1 scores ranging from 79% to 89% using a Random Forest classifier. Finally, we measure the importance of different features using SHAP values and provide implications for improving the adoption rates of nearly a million farmers across five states in India.

Tiplines to Combat Misinformation on Encrypted Platforms: A Case Study of the 2019 Indian Election on WhatsApp

Jun 08, 2021

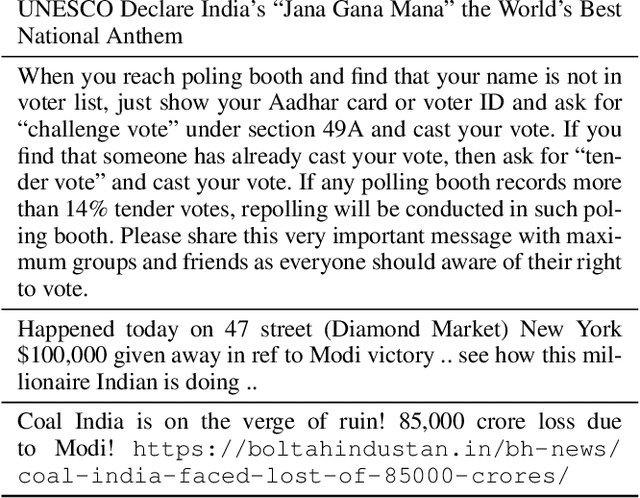

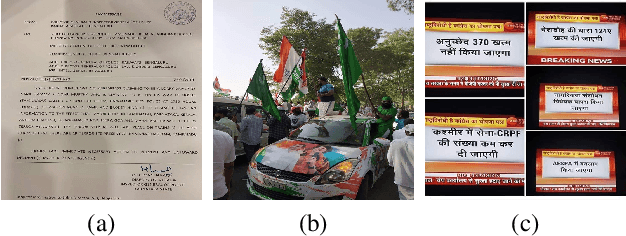

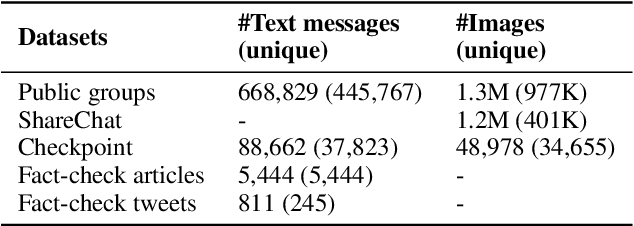

Abstract:WhatsApp is a popular chat application used by over 2 billion users worldwide. However, due to end-to-end encryption, there is currently no easy way to fact-check content on WhatsApp at scale. In this paper, we analyze the usefulness of a crowd-sourced system on WhatsApp through which users can submit "tips" containing messages they want fact-checked. We compare the tips sent to a WhatsApp tipline run during the 2019 Indian national elections with the messages circulating in large, public groups on WhatsApp and other social media platforms during the same period. We find that tiplines are a very useful lens into WhatsApp conversations: a significant fraction of messages and images sent to the tipline match with the content being shared on public WhatsApp groups and other social media. Our analysis also shows that tiplines cover the most popular content well, and a majority of such content is often shared to the tipline before appearing in large, public WhatsApp groups. Overall, the analysis suggests tiplines can be an effective source for discovering content to fact-check.

Claim Matching Beyond English to Scale Global Fact-Checking

Jun 01, 2021

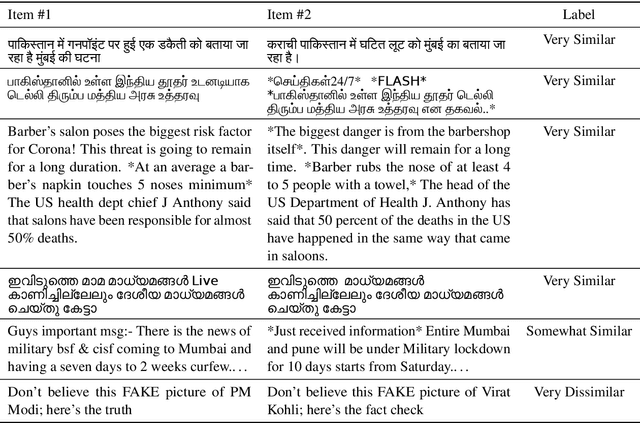

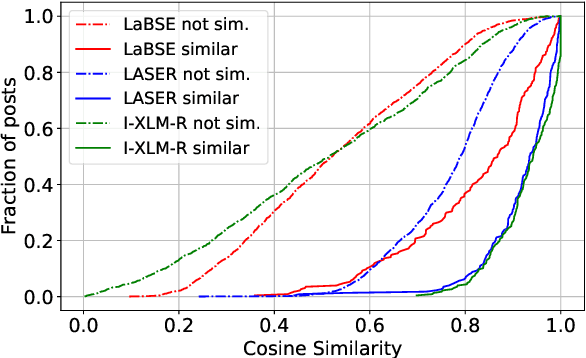

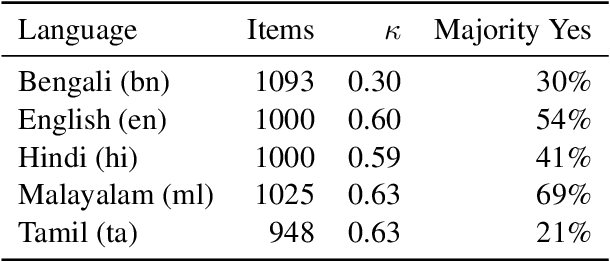

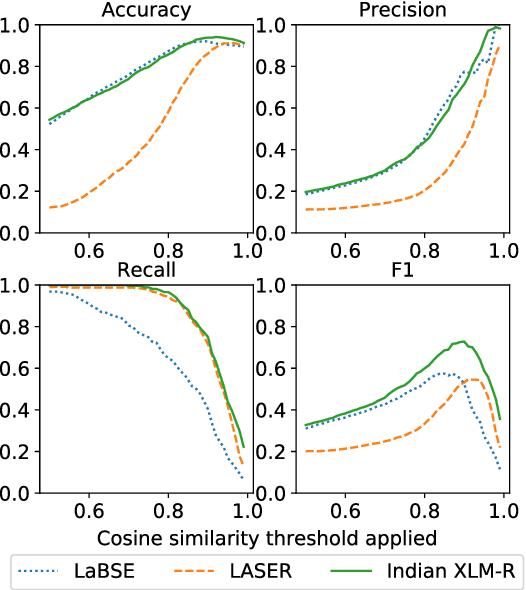

Abstract:Manual fact-checking does not scale well to serve the needs of the internet. This issue is further compounded in non-English contexts. In this paper, we discuss claim matching as a possible solution to scale fact-checking. We define claim matching as the task of identifying pairs of textual messages containing claims that can be served with one fact-check. We construct a novel dataset of WhatsApp tipline and public group messages alongside fact-checked claims that are first annotated for containing "claim-like statements" and then matched with potentially similar items and annotated for claim matching. Our dataset contains content in high-resource (English, Hindi) and lower-resource (Bengali, Malayalam, Tamil) languages. We train our own embedding model using knowledge distillation and a high-quality "teacher" model in order to address the imbalance in embedding quality between the low- and high-resource languages in our dataset. We provide evaluations on the performance of our solution and compare with baselines and existing state-of-the-art multilingual embedding models, namely LASER and LaBSE. We demonstrate that our performance exceeds LASER and LaBSE in all settings. We release our annotated datasets, codebooks, and trained embedding model to allow for further research.

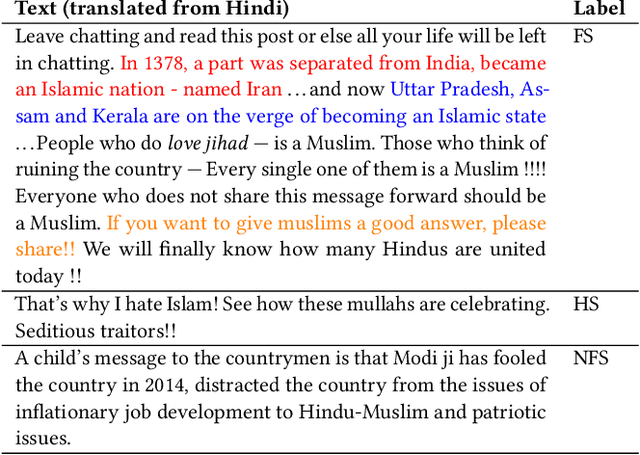

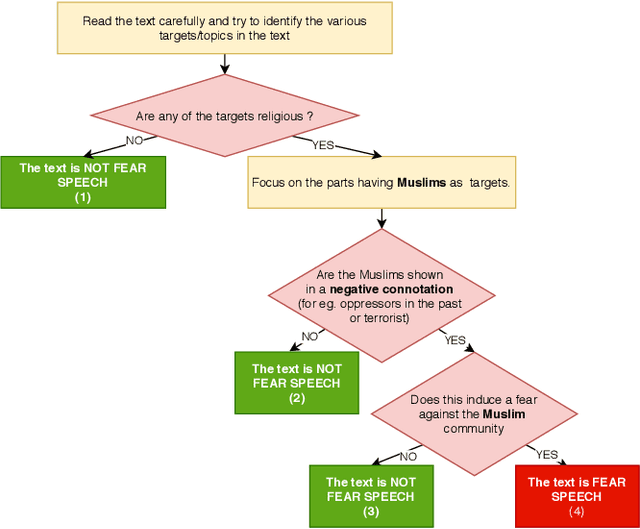

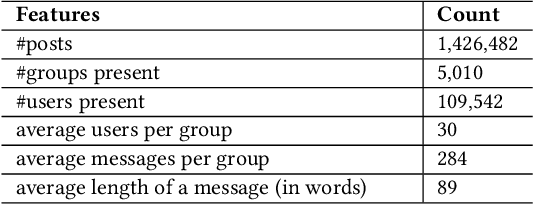

"Short is the Road that Leads from Fear to Hate": Fear Speech in Indian WhatsApp Groups

Feb 07, 2021

Abstract:WhatsApp is the most popular messaging app in the world. Due to its popularity, WhatsApp has become a powerful and cheap tool for political campaigning being widely used during the 2019 Indian general election, where it was used to connect to the voters on a large scale. Along with the campaigning, there have been reports that WhatsApp has also become a breeding ground for harmful speech against various protected groups and religious minorities. Many such messages attempt to instil fear among the population about a specific (minority) community. According to research on inter-group conflict, such `fear speech' messages could have a lasting impact and might lead to real offline violence. In this paper, we perform the first large scale study on fear speech across thousands of public WhatsApp groups discussing politics in India. We curate a new dataset and try to characterize fear speech from this dataset. We observe that users writing fear speech messages use various events and symbols to create the illusion of fear among the reader about a target community. We build models to classify fear speech and observe that current state-of-the-art NLP models do not perform well at this task. Fear speech messages tend to spread faster and could potentially go undetected by classifiers built to detect traditional toxic speech due to their low toxic nature. Finally, using a novel methodology to target users with Facebook ads, we conduct a survey among the users of these WhatsApp groups to understand the types of users who consume and share fear speech. We believe that this work opens up new research questions that are very different from tackling hate speech which the research community has been traditionally involved in.

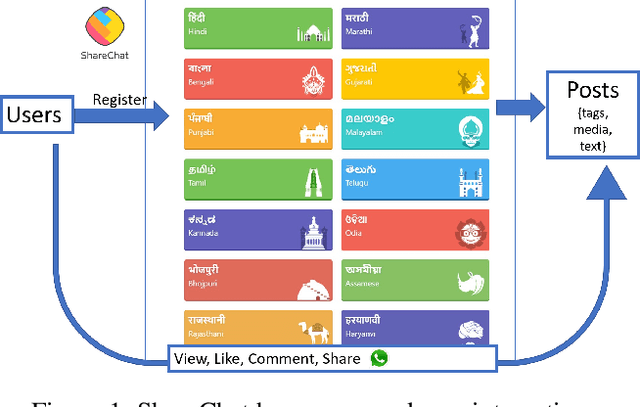

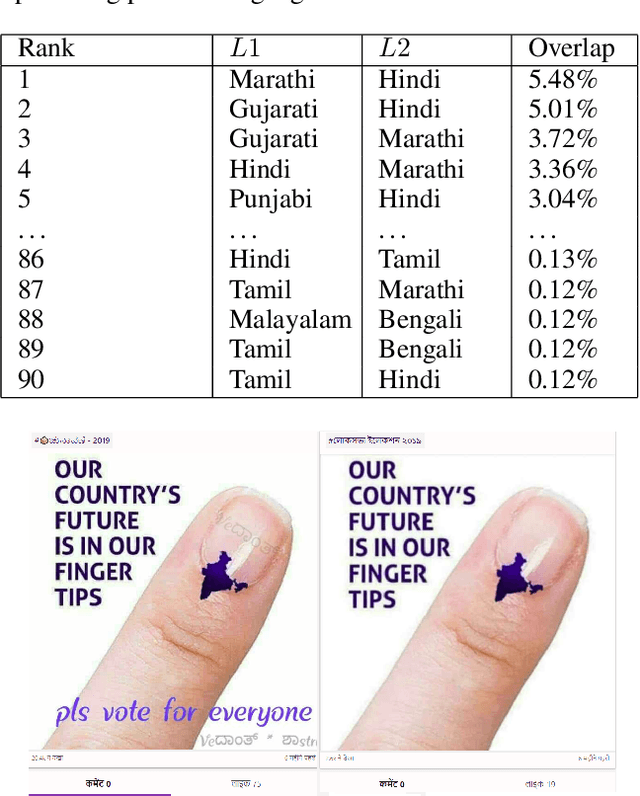

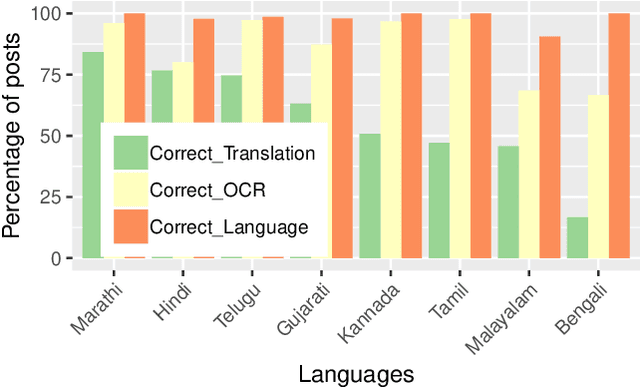

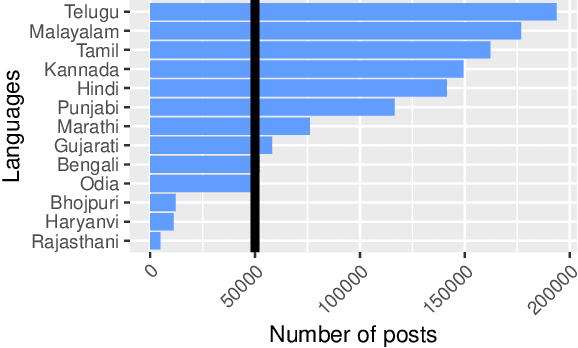

Characterising User Content on a Multi-lingual Social Network

Apr 23, 2020

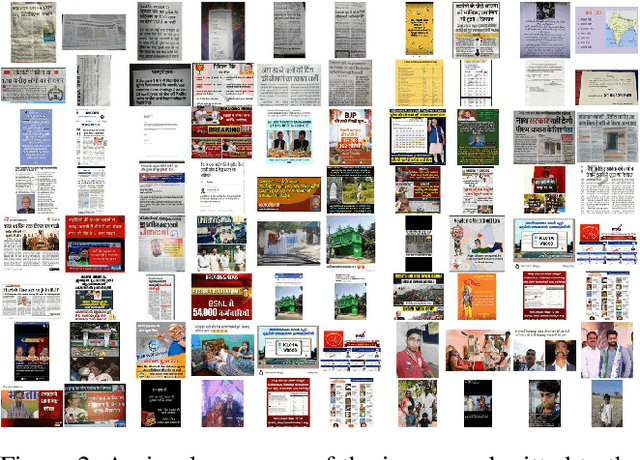

Abstract:Social media has been on the vanguard of political information diffusion in the 21st century. Most studies that look into disinformation, political influence and fake-news focus on mainstream social media platforms. This has inevitably made English an important factor in our current understanding of political activity on social media. As a result, there has only been a limited number of studies into a large portion of the world, including the largest, multilingual and multi-cultural democracy: India. In this paper we present our characterisation of a multilingual social network in India called ShareChat. We collect an exhaustive dataset across 72 weeks before and during the Indian general elections of 2019, across 14 languages. We investigate the cross lingual dynamics by clustering visually similar images together, and exploring how they move across language barriers. We find that Telugu, Malayalam, Tamil and Kannada languages tend to be dominant in soliciting political images (often referred to as memes), and posts from Hindi have the largest cross-lingual diffusion across ShareChat (as well as images containing text in English). In the case of images containing text that cross language barriers, we see that language translation is used to widen the accessibility. That said, we find cases where the same image is associated with very different text (and therefore meanings). This initial characterisation paves the way for more advanced pipelines to understand the dynamics of fake and political content in a multi-lingual and non-textual setting.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge