David Mayo

BrainBits: How Much of the Brain are Generative Reconstruction Methods Using?

Nov 05, 2024

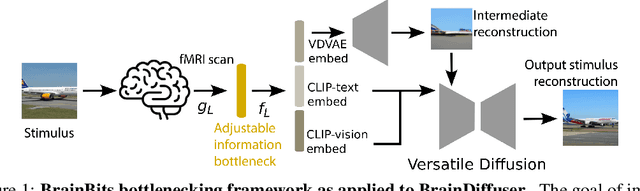

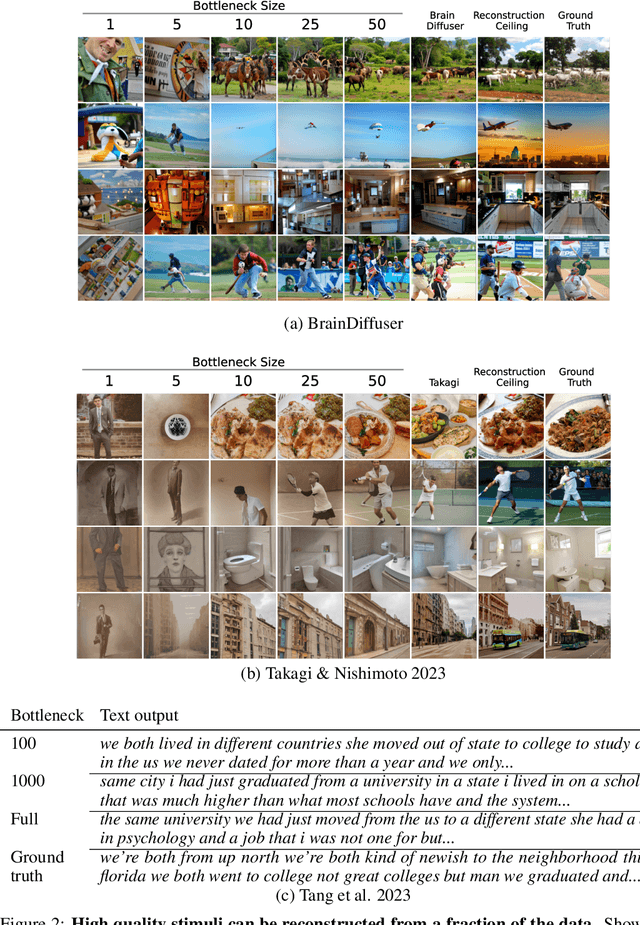

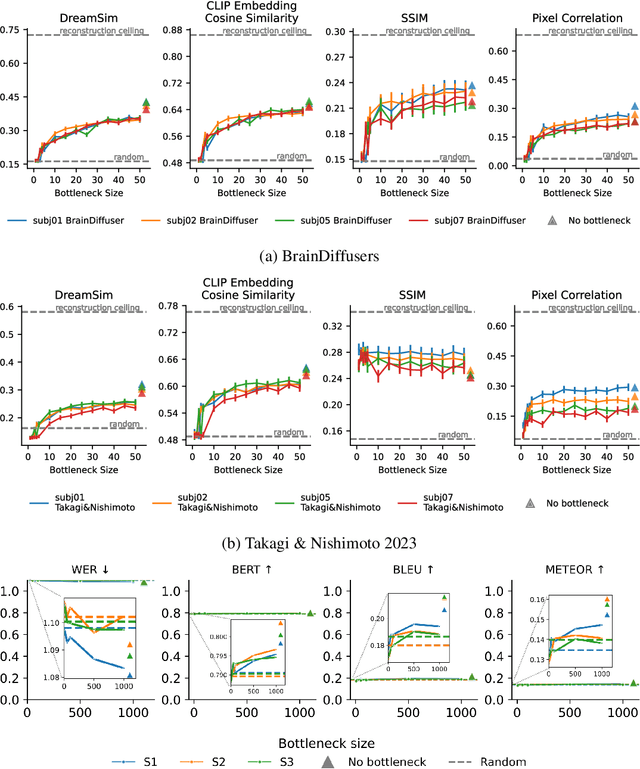

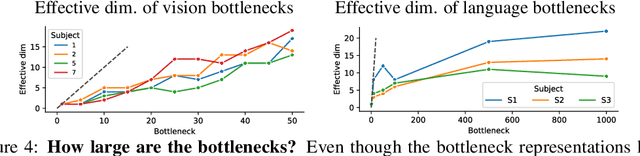

Abstract:When evaluating stimuli reconstruction results it is tempting to assume that higher fidelity text and image generation is due to an improved understanding of the brain or more powerful signal extraction from neural recordings. However, in practice, new reconstruction methods could improve performance for at least three other reasons: learning more about the distribution of stimuli, becoming better at reconstructing text or images in general, or exploiting weaknesses in current image and/or text evaluation metrics. Here we disentangle how much of the reconstruction is due to these other factors vs. productively using the neural recordings. We introduce BrainBits, a method that uses a bottleneck to quantify the amount of signal extracted from neural recordings that is actually necessary to reproduce a method's reconstruction fidelity. We find that it takes surprisingly little information from the brain to produce reconstructions with high fidelity. In these cases, it is clear that the priors of the methods' generative models are so powerful that the outputs they produce extrapolate far beyond the neural signal they decode. Given that reconstructing stimuli can be improved independently by either improving signal extraction from the brain or by building more powerful generative models, improving the latter may fool us into thinking we are improving the former. We propose that methods should report a method-specific random baseline, a reconstruction ceiling, and a curve of performance as a function of bottleneck size, with the ultimate goal of using more of the neural recordings.

Using Multimodal Deep Neural Networks to Disentangle Language from Visual Aesthetics

Oct 31, 2024

Abstract:When we experience a visual stimulus as beautiful, how much of that experience derives from perceptual computations we cannot describe versus conceptual knowledge we can readily translate into natural language? Disentangling perception from language in visually-evoked affective and aesthetic experiences through behavioral paradigms or neuroimaging is often empirically intractable. Here, we circumnavigate this challenge by using linear decoding over the learned representations of unimodal vision, unimodal language, and multimodal (language-aligned) deep neural network (DNN) models to predict human beauty ratings of naturalistic images. We show that unimodal vision models (e.g. SimCLR) account for the vast majority of explainable variance in these ratings. Language-aligned vision models (e.g. SLIP) yield small gains relative to unimodal vision. Unimodal language models (e.g. GPT2) conditioned on visual embeddings to generate captions (via CLIPCap) yield no further gains. Caption embeddings alone yield less accurate predictions than image and caption embeddings combined (concatenated). Taken together, these results suggest that whatever words we may eventually find to describe our experience of beauty, the ineffable computations of feedforward perception may provide sufficient foundation for that experience.

Training the Untrainable: Introducing Inductive Bias via Representational Alignment

Oct 26, 2024

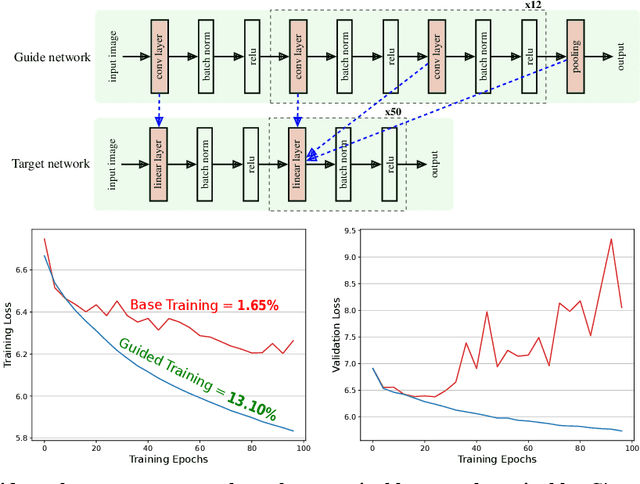

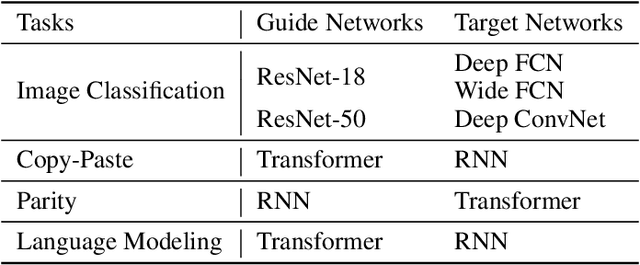

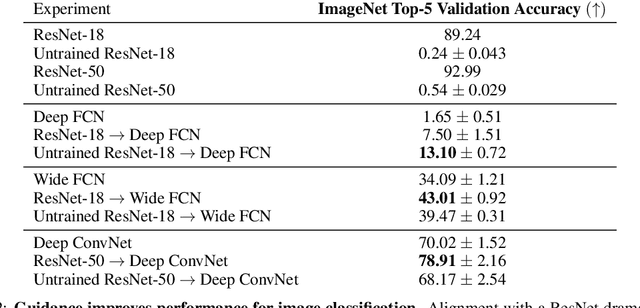

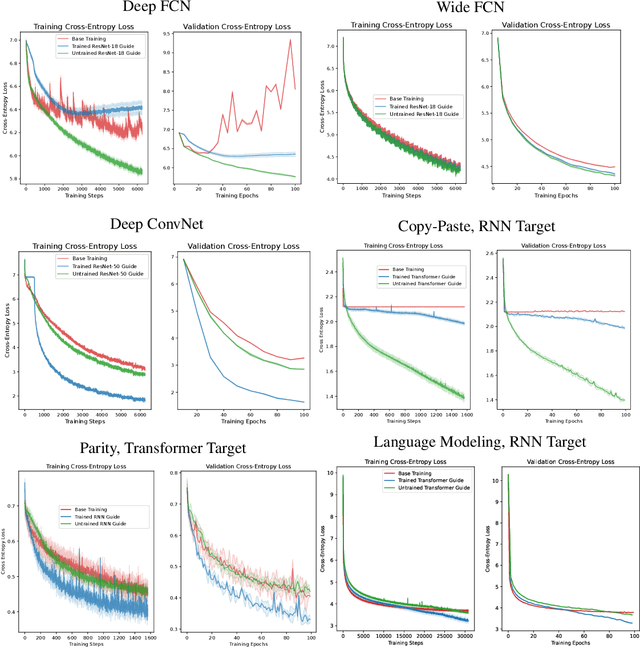

Abstract:We demonstrate that architectures which traditionally are considered to be ill-suited for a task can be trained using inductive biases from another architecture. Networks are considered untrainable when they overfit, underfit, or converge to poor results even when tuning their hyperparameters. For example, plain fully connected networks overfit on object recognition while deep convolutional networks without residual connections underfit. The traditional answer is to change the architecture to impose some inductive bias, although what that bias is remains unknown. We introduce guidance, where a guide network guides a target network using a neural distance function. The target is optimized to perform well and to match its internal representations, layer-by-layer, to those of the guide; the guide is unchanged. If the guide is trained, this transfers over part of the architectural prior and knowledge of the guide to the target. If the guide is untrained, this transfers over only part of the architectural prior of the guide. In this manner, we can investigate what kinds of priors different architectures place on untrainable networks such as fully connected networks. We demonstrate that this method overcomes the immediate overfitting of fully connected networks on vision tasks, makes plain CNNs competitive to ResNets, closes much of the gap between plain vanilla RNNs and Transformers, and can even help Transformers learn tasks which RNNs can perform more easily. We also discover evidence that better initializations of fully connected networks likely exist to avoid overfitting. Our method provides a mathematical tool to investigate priors and architectures, and in the long term, may demystify the dark art of architecture creation, even perhaps turning architectures into a continuous optimizable parameter of the network.

Developing a Series of AI Challenges for the United States Department of the Air Force

Jul 14, 2022

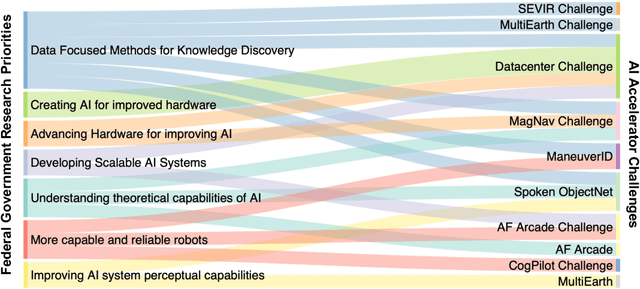

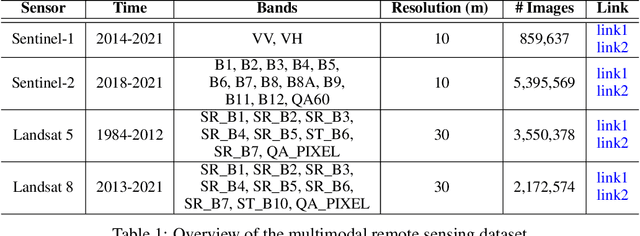

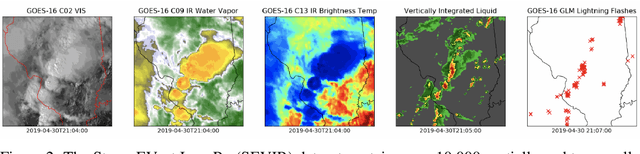

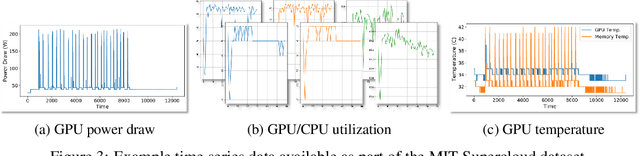

Abstract:Through a series of federal initiatives and orders, the U.S. Government has been making a concerted effort to ensure American leadership in AI. These broad strategy documents have influenced organizations such as the United States Department of the Air Force (DAF). The DAF-MIT AI Accelerator is an initiative between the DAF and MIT to bridge the gap between AI researchers and DAF mission requirements. Several projects supported by the DAF-MIT AI Accelerator are developing public challenge problems that address numerous Federal AI research priorities. These challenges target priorities by making large, AI-ready datasets publicly available, incentivizing open-source solutions, and creating a demand signal for dual use technologies that can stimulate further research. In this article, we describe these public challenges being developed and how their application contributes to scientific advances.

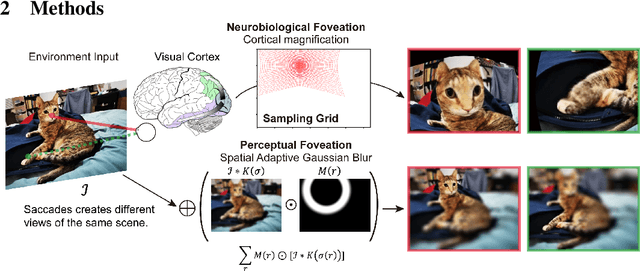

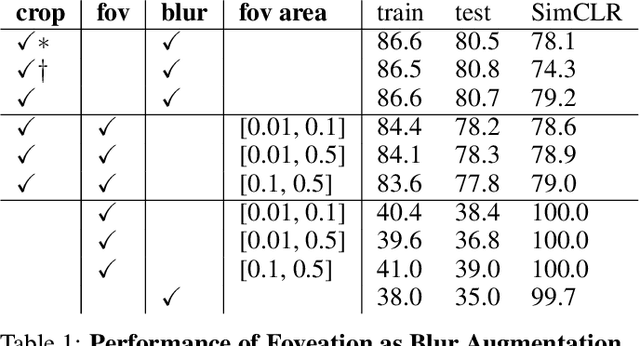

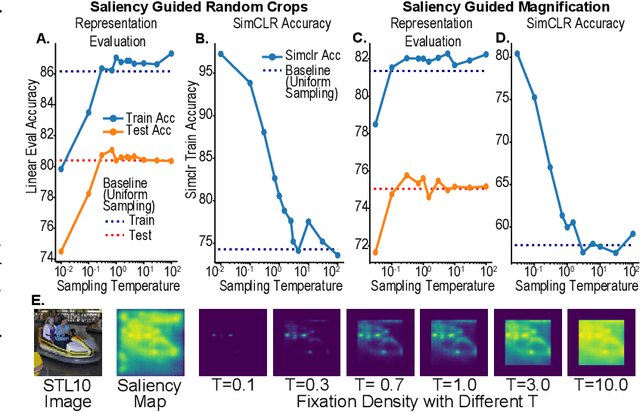

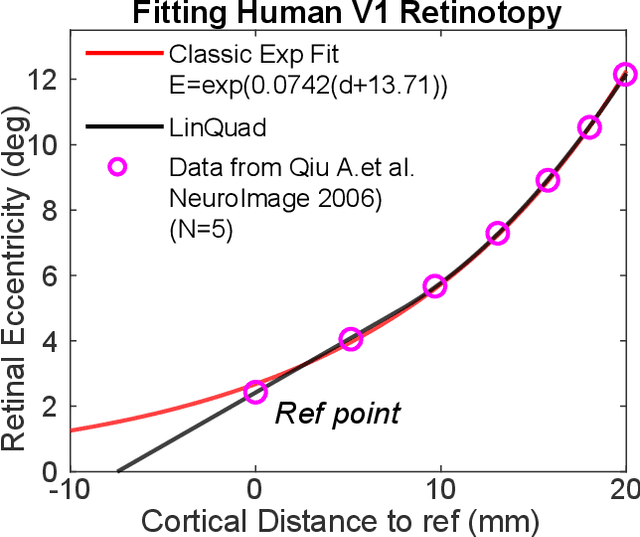

On the use of Cortical Magnification and Saccades as Biological Proxies for Data Augmentation

Dec 14, 2021

Abstract:Self-supervised learning is a powerful way to learn useful representations from natural data. It has also been suggested as one possible means of building visual representation in humans, but the specific objective and algorithm are unknown. Currently, most self-supervised methods encourage the system to learn an invariant representation of different transformations of the same image in contrast to those of other images. However, such transformations are generally non-biologically plausible, and often consist of contrived perceptual schemes such as random cropping and color jittering. In this paper, we attempt to reverse-engineer these augmentations to be more biologically or perceptually plausible while still conferring the same benefits for encouraging robust representation. Critically, we find that random cropping can be substituted by cortical magnification, and saccade-like sampling of the image could also assist the representation learning. The feasibility of these transformations suggests a potential way that biological visual systems could implement self-supervision. Further, they break the widely accepted spatially-uniform processing assumption used in many computer vision algorithms, suggesting a role for spatially-adaptive computation in humans and machines alike. Our code and demo can be found here.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge