Anand Siththaranjan

AI Alignment with Changing and Influenceable Reward Functions

May 28, 2024

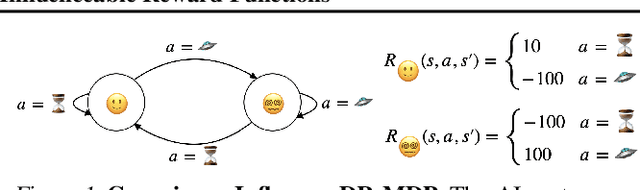

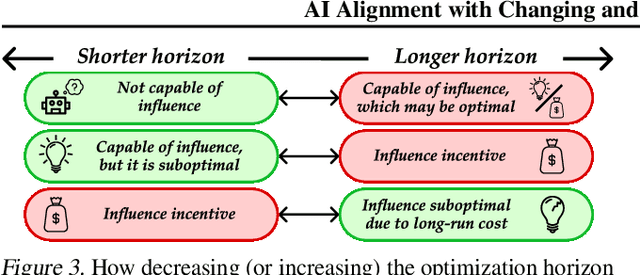

Abstract:Existing AI alignment approaches assume that preferences are static, which is unrealistic: our preferences change, and may even be influenced by our interactions with AI systems themselves. To clarify the consequences of incorrectly assuming static preferences, we introduce Dynamic Reward Markov Decision Processes (DR-MDPs), which explicitly model preference changes and the AI's influence on them. We show that despite its convenience, the static-preference assumption may undermine the soundness of existing alignment techniques, leading them to implicitly reward AI systems for influencing user preferences in ways users may not truly want. We then explore potential solutions. First, we offer a unifying perspective on how an agent's optimization horizon may partially help reduce undesirable AI influence. Then, we formalize different notions of AI alignment that account for preference change from the outset. Comparing the strengths and limitations of 8 such notions of alignment, we find that they all either err towards causing undesirable AI influence, or are overly risk-averse, suggesting that a straightforward solution to the problems of changing preferences may not exist. As there is no avoiding grappling with changing preferences in real-world settings, this makes it all the more important to handle these issues with care, balancing risks and capabilities. We hope our work can provide conceptual clarity and constitute a first step towards AI alignment practices which explicitly account for (and contend with) the changing and influenceable nature of human preferences.

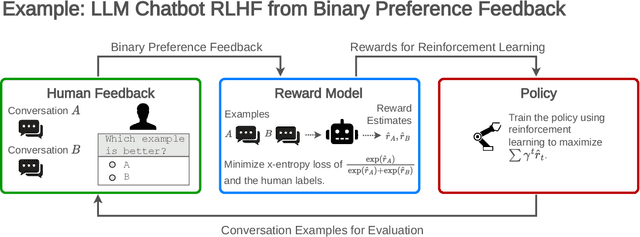

Distributional Preference Learning: Understanding and Accounting for Hidden Context in RLHF

Dec 13, 2023Abstract:In practice, preference learning from human feedback depends on incomplete data with hidden context. Hidden context refers to data that affects the feedback received, but which is not represented in the data used to train a preference model. This captures common issues of data collection, such as having human annotators with varied preferences, cognitive processes that result in seemingly irrational behavior, and combining data labeled according to different criteria. We prove that standard applications of preference learning, including reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), implicitly aggregate over hidden contexts according to a well-known voting rule called Borda count. We show this can produce counter-intuitive results that are very different from other methods which implicitly aggregate via expected utility. Furthermore, our analysis formalizes the way that preference learning from users with diverse values tacitly implements a social choice function. A key implication of this result is that annotators have an incentive to misreport their preferences in order to influence the learned model, leading to vulnerabilities in the deployment of RLHF. As a step towards mitigating these problems, we introduce a class of methods called distributional preference learning (DPL). DPL methods estimate a distribution of possible score values for each alternative in order to better account for hidden context. Experimental results indicate that applying DPL to RLHF for LLM chatbots identifies hidden context in the data and significantly reduces subsequent jailbreak vulnerability. Our code and data are available at https://github.com/cassidylaidlaw/hidden-context

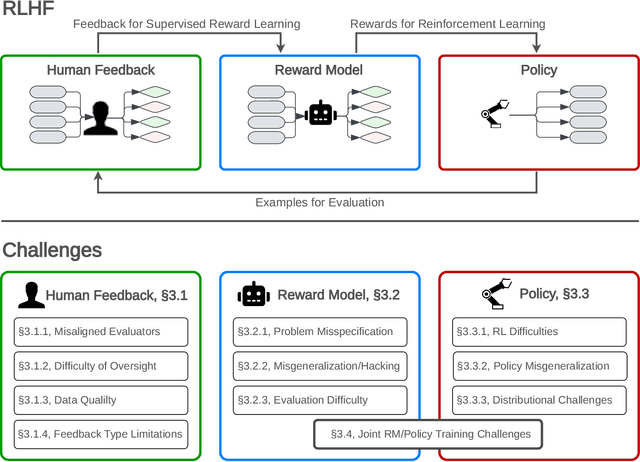

Open Problems and Fundamental Limitations of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

Jul 27, 2023

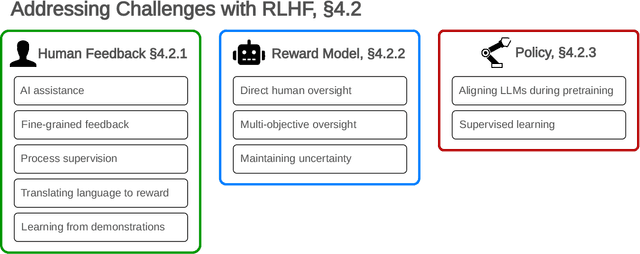

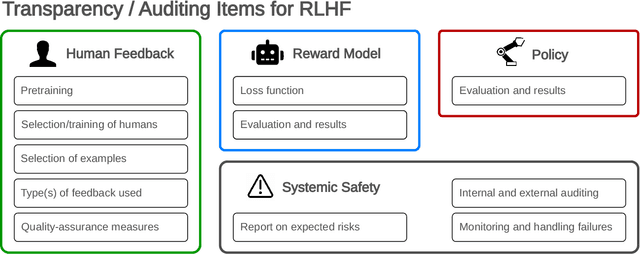

Abstract:Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) is a technique for training AI systems to align with human goals. RLHF has emerged as the central method used to finetune state-of-the-art large language models (LLMs). Despite this popularity, there has been relatively little public work systematizing its flaws. In this paper, we (1) survey open problems and fundamental limitations of RLHF and related methods; (2) overview techniques to understand, improve, and complement RLHF in practice; and (3) propose auditing and disclosure standards to improve societal oversight of RLHF systems. Our work emphasizes the limitations of RLHF and highlights the importance of a multi-faceted approach to the development of safer AI systems.

Analyzing Human Models that Adapt Online

Mar 09, 2021

Abstract:Predictive human models often need to adapt their parameters online from human data. This raises previously ignored safety-related questions for robots relying on these models such as what the model could learn online and how quickly could it learn it. For instance, when will the robot have a confident estimate in a nearby human's goal? Or, what parameter initializations guarantee that the robot can learn the human's preferences in a finite number of observations? To answer such analysis questions, our key idea is to model the robot's learning algorithm as a dynamical system where the state is the current model parameter estimate and the control is the human data the robot observes. This enables us to leverage tools from reachability analysis and optimal control to compute the set of hypotheses the robot could learn in finite time, as well as the worst and best-case time it takes to learn them. We demonstrate the utility of our analysis tool in four human-robot domains, including autonomous driving and indoor navigation.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge