Aman Bhatta

Are you In or Out (of gallery)? Wisdom from the Same-Identity Crowd

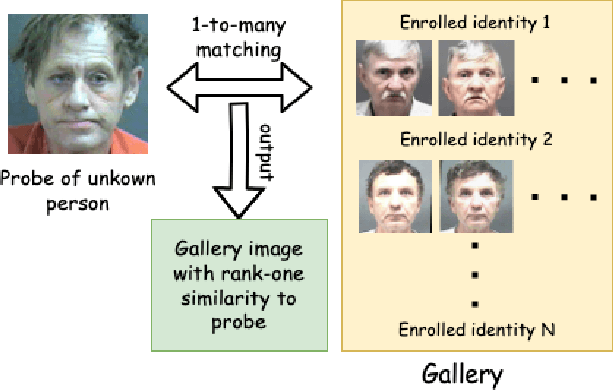

Aug 08, 2025Abstract:A central problem in one-to-many facial identification is that the person in the probe image may or may not have enrolled image(s) in the gallery; that is, may be In-gallery or Out-of-gallery. Past approaches to detect when a rank-one result is Out-of-gallery have mostly focused on finding a suitable threshold on the similarity score. We take a new approach, using the additional enrolled images of the identity with the rank-one result to predict if the rank-one result is In-gallery / Out-of-gallery. Given a gallery of identities and images, we generate In-gallery and Out-of-gallery training data by extracting the ranks of additional enrolled images corresponding to the rank-one identity. We then train a classifier to utilize this feature vector to predict whether a rank-one result is In-gallery or Out-of-gallery. Using two different datasets and four different matchers, we present experimental results showing that our approach is viable for mugshot quality probe images, and also, importantly, for probes degraded by blur, reduced resolution, atmospheric turbulence and sunglasses. We also analyze results across demographic groups, and show that In-gallery / Out-of-gallery classification accuracy is similar across demographics. Our approach has the potential to provide an objective estimate of whether a one-to-many facial identification is Out-of-gallery, and thereby to reduce false positive identifications, wrongful arrests, and wasted investigative time. Interestingly, comparing the results of older deep CNN-based face matchers with newer ones suggests that the effectiveness of our Out-of-gallery detection approach emerges only with matchers trained using advanced margin-based loss functions.

What is a Goldilocks Face Verification Test Set?

May 24, 2024

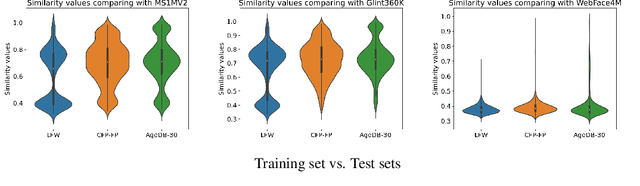

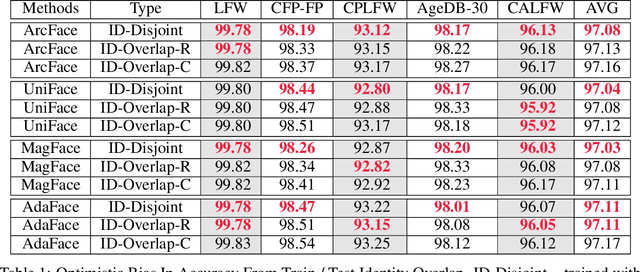

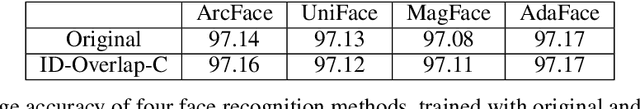

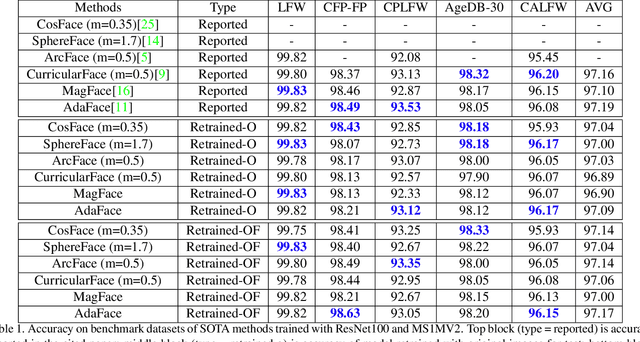

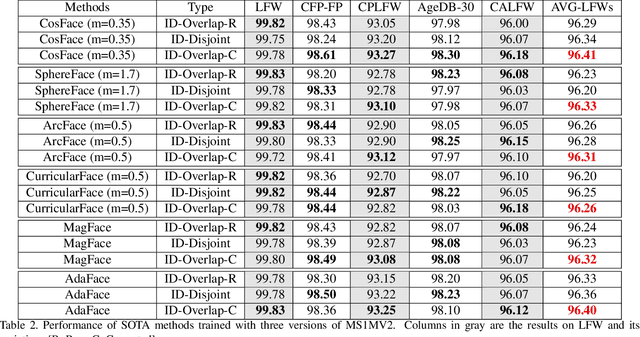

Abstract:Face Recognition models are commonly trained with web-scraped datasets containing millions of images and evaluated on test sets emphasizing pose, age and mixed attributes. With train and test sets both assembled from web-scraped images, it is critical to ensure disjoint sets of identities between train and test sets. However, existing train and test sets have not considered this. Moreover, as accuracy levels become saturated, such as LFW $>99.8\%$, more challenging test sets are needed. We show that current train and test sets are generally not identity- or even image-disjoint, and that this results in an optimistic bias in the estimated accuracy. In addition, we show that identity-disjoint folds are important in the 10-fold cross-validation estimate of test accuracy. To better support continued advances in face recognition, we introduce two "Goldilocks" test sets, Hadrian and Eclipse. The former emphasizes challenging facial hairstyles and latter emphasizes challenging over- and under-exposure conditions. Images in both datasets are from a large, controlled-acquisition (not web-scraped) dataset, so they are identity- and image-disjoint with all popular training sets. Accuracy for these new test sets generally falls below that observed on LFW, CPLFW, CALFW, CFP-FP and AgeDB-30, showing that these datasets represent important dimensions for improvement of face recognition. The datasets are available at: \url{https://github.com/HaiyuWu/SOTA-Face-Recognition-Train-and-Test}

Identity Overlap Between Face Recognition Train/Test Data: Causing Optimistic Bias in Accuracy Measurement

May 15, 2024

Abstract:A fundamental tenet of pattern recognition is that overlap between training and testing sets causes an optimistic accuracy estimate. Deep CNNs for face recognition are trained for N-way classification of the identities in the training set. Accuracy is commonly estimated as average 10-fold classification accuracy on image pairs from test sets such as LFW, CALFW, CPLFW, CFP-FP and AgeDB-30. Because train and test sets have been independently assembled, images and identities in any given test set may also be present in any given training set. In particular, our experiments reveal a surprising degree of identity and image overlap between the LFW family of test sets and the MS1MV2 training set. Our experiments also reveal identity label noise in MS1MV2. We compare accuracy achieved with same-size MS1MV2 subsets that are identity-disjoint and not identity-disjoint with LFW, to reveal the size of the optimistic bias. Using more challenging test sets from the LFW family, we find that the size of the optimistic bias is larger for more challenging test sets. Our results highlight the lack of and the need for identity-disjoint train and test methodology in face recognition research.

CRAFT: Contextual Re-Activation of Filters for face recognition Training

Dec 05, 2023

Abstract:The first layer of a deep CNN backbone applies filters to an image to extract the basic features available to later layers. During training, some filters may go inactive, mean ing all weights in the filter approach zero. An inactive fil ter in the final model represents a missed opportunity to extract a useful feature. This phenomenon is especially prevalent in specialized CNNs such as for face recogni tion (as opposed to, e.g., ImageNet). For example, in one the most widely face recognition model (ArcFace), about half of the convolution filters in the first layer are inactive. We propose a novel approach designed and tested specif ically for face recognition networks, known as "CRAFT: Contextual Re-Activation of Filters for Face Recognition Training". CRAFT identifies inactive filters during training and reinitializes them based on the context of strong filters at that stage in training. We show that CRAFT reduces fraction of inactive filters from 44% to 32% on average and discovers filter patterns not found by standard training. Compared to standard training without reactivation, CRAFT demonstrates enhanced model accuracy on standard face-recognition benchmark datasets including AgeDB-30, CPLFW, LFW, CALFW, and CFP-FP, as well as on more challenging datasets like IJBB and IJBC.

Our Deep CNN Face Matchers Have Developed Achromatopsia

Sep 11, 2023

Abstract:Modern deep CNN face matchers are trained on datasets containing color images. We show that such matchers achieve essentially the same accuracy on the grayscale or the color version of a set of test images. We then consider possible causes for deep CNN face matchers ``not seeing color''. Popular web-scraped face datasets actually have 30 to 60\% of their identities with one or more grayscale images. We analyze whether this grayscale element in the training set impacts the accuracy achieved, and conclude that it does not. Further, we show that even with a 100\% grayscale training set, comparable accuracy is achieved on color or grayscale test images. Then we show that the skin region of an individual's images in a web-scraped training set exhibit significant variation in their mapping to color space. This suggests that color, at least for web-scraped, in-the-wild face datasets, carries limited identity-related information for training state-of-the-art matchers. Finally, we verify that comparable accuracy is achieved from training using single-channel grayscale images, implying that a larger dataset can be used within the same memory limit, with a less computationally intensive early layer.

Demographic Disparities in 1-to-Many Facial Identification

Sep 08, 2023

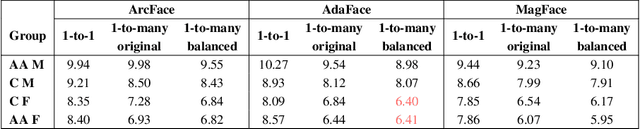

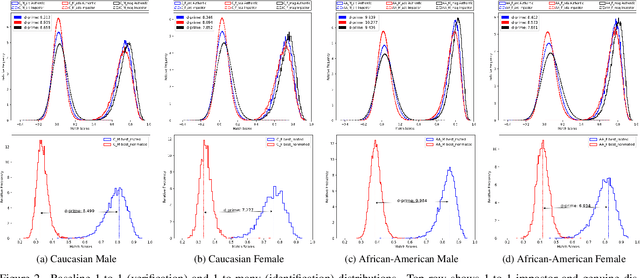

Abstract:Most studies to date that have examined demographic variations in face recognition accuracy have analyzed 1-to-1 matching accuracy, using images that could be described as "government ID quality". This paper analyzes the accuracy of 1-to-many facial identification across demographic groups, and in the presence of blur and reduced resolution in the probe image as might occur in "surveillance camera quality" images. Cumulative match characteristic curves(CMC) are not appropriate for comparing propensity for rank-one recognition errors across demographics, and so we introduce three metrics for this: (1) d' metric between mated and non-mated score distributions, (2) absolute score difference between thresholds in the high-similarity tail of the non-mated and the low-similarity tail of the mated distribution, and (3) distribution of (mated - non-mated rank one scores) across the set of probe images. We find that demographic variation in 1-to-many accuracy does not entirely follow what has been observed in 1-to-1 matching accuracy. Also, different from 1-to-1 accuracy, demographic comparison of 1-to-many accuracy can be affected by different numbers of identities and images across demographics. Finally, we show that increased blur in the probe image, or reduced resolution of the face in the probe image, can significantly increase the false positive identification rate. And we show that the demographic variation in these high blur or low resolution conditions is much larger for male/ female than for African-American / Caucasian. The point that 1-to-many accuracy can potentially collapse in the context of processing "surveillance camera quality" probe images against a "government ID quality" gallery is an important one.

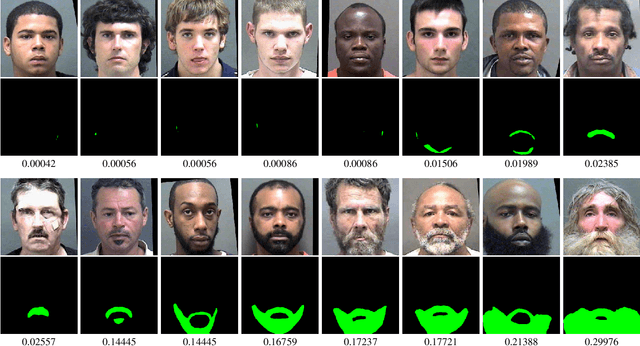

Beard Segmentation and Recognition Bias

Aug 30, 2023

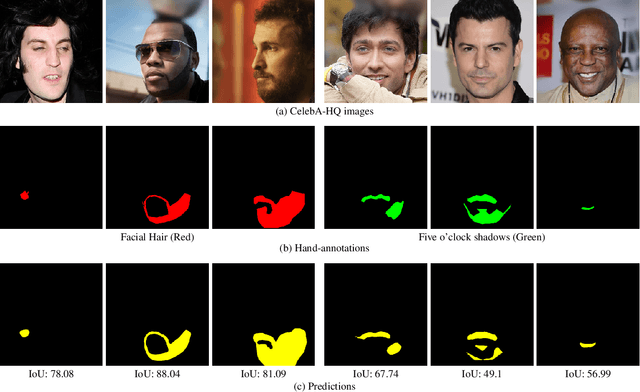

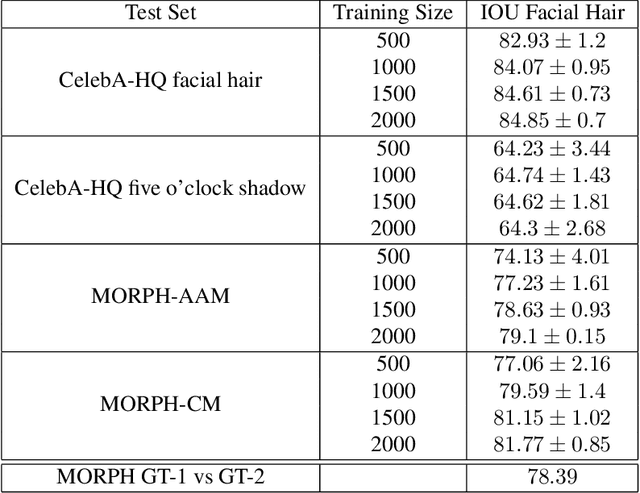

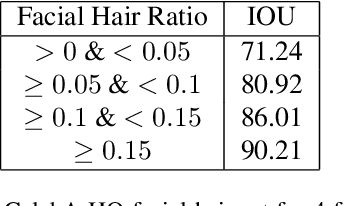

Abstract:A person's facial hairstyle, such as presence and size of beard, can significantly impact face recognition accuracy. There are publicly-available deep networks that achieve reasonable accuracy at binary attribute classification, such as beard / no beard, but few if any that segment the facial hair region. To investigate the effect of facial hair in a rigorous manner, we first created a set of fine-grained facial hair annotations to train a segmentation model and evaluate its accuracy across African-American and Caucasian face images. We then use our facial hair segmentations to categorize image pairs according to the degree of difference or similarity in the facial hairstyle. We find that the False Match Rate (FMR) for image pairs with different categories of facial hairstyle varies by a factor of over 10 for African-American males and over 25 for Caucasian males. To reduce the bias across image pairs with different facial hairstyles, we propose a scheme for adaptive thresholding based on facial hairstyle similarity. Evaluation on a subject-disjoint set of images shows that adaptive similarity thresholding based on facial hairstyles of the image pair reduces the ratio between the highest and lowest FMR across facial hairstyle categories for African-American from 10.7 to 1.8 and for Caucasians from 25.9 to 1.3. Facial hair annotations and facial hair segmentation model will be publicly available.

Logical Consistency and Greater Descriptive Power for Facial Hair Attribute Learning

Feb 22, 2023Abstract:Face attribute research has so far used only simple binary attributes for facial hair; e.g., beard / no beard. We have created a new, more descriptive facial hair annotation scheme and applied it to create a new facial hair attribute dataset, FH37K. Face attribute research also so far has not dealt with logical consistency and completeness. For example, in prior research, an image might be classified as both having no beard and also having a goatee (a type of beard). We show that the test accuracy of previous classification methods on facial hair attribute classification drops significantly if logical consistency of classifications is enforced. We propose a logically consistent prediction loss, LCPLoss, to aid learning of logical consistency across attributes, and also a label compensation training strategy to eliminate the problem of no positive prediction across a set of related attributes. Using an attribute classifier trained on FH37K, we investigate how facial hair affects face recognition accuracy, including variation across demographics. Results show that similarity and difference in facial hairstyle have important effects on the impostor and genuine score distributions in face recognition.

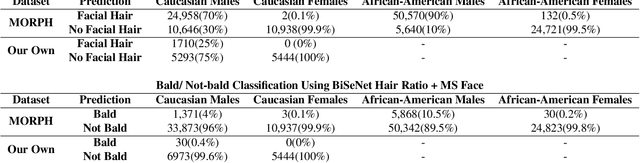

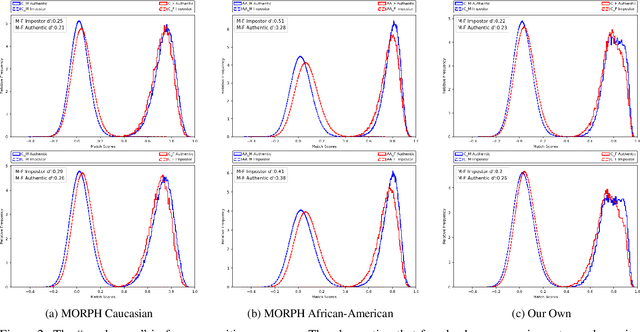

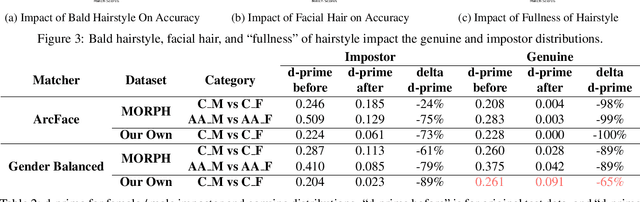

The Gender Gap in Face Recognition Accuracy Is a Hairy Problem

Jun 10, 2022

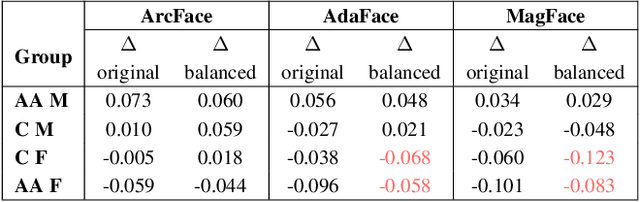

Abstract:It is broadly accepted that there is a "gender gap" in face recognition accuracy, with females having higher false match and false non-match rates. However, relatively little is known about the cause(s) of this gender gap. Even the recent NIST report on demographic effects lists "analyze cause and effect" under "what we did not do". We first demonstrate that female and male hairstyles have important differences that impact face recognition accuracy. In particular, compared to females, male facial hair contributes to creating a greater average difference in appearance between different male faces. We then demonstrate that when the data used to estimate recognition accuracy is balanced across gender for how hairstyles occlude the face, the initially observed gender gap in accuracy largely disappears. We show this result for two different matchers, and analyzing images of Caucasians and of African-Americans. These results suggest that future research on demographic variation in accuracy should include a check for balanced quality of the test data as part of the problem formulation. To promote reproducible research, matchers, attribute classifiers, and datasets used in this research are/will be publicly available.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge