Tiago Marques

Explicitly Modeling Pre-Cortical Vision with a Neuro-Inspired Front-End Improves CNN Robustness

Sep 25, 2024Abstract:While convolutional neural networks (CNNs) excel at clean image classification, they struggle to classify images corrupted with different common corruptions, limiting their real-world applicability. Recent work has shown that incorporating a CNN front-end block that simulates some features of the primate primary visual cortex (V1) can improve overall model robustness. Here, we expand on this approach by introducing two novel biologically-inspired CNN model families that incorporate a new front-end block designed to simulate pre-cortical visual processing. RetinaNet, a hybrid architecture containing the novel front-end followed by a standard CNN back-end, shows a relative robustness improvement of 12.3% when compared to the standard model; and EVNet, which further adds a V1 block after the pre-cortical front-end, shows a relative gain of 18.5%. The improvement in robustness was observed for all the different corruption categories, though accompanied by a small decrease in clean image accuracy, and generalized to a different back-end architecture. These findings show that simulating multiple stages of early visual processing in CNN early layers provides cumulative benefits for model robustness.

Matching the Neuronal Representations of V1 is Necessary to Improve Robustness in CNNs with V1-like Front-ends

Oct 16, 2023Abstract:While some convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have achieved great success in object recognition, they struggle to identify objects in images corrupted with different types of common noise patterns. Recently, it was shown that simulating computations in early visual areas at the front of CNNs leads to improvements in robustness to image corruptions. Here, we further explore this result and show that the neuronal representations that emerge from precisely matching the distribution of RF properties found in primate V1 is key for this improvement in robustness. We built two variants of a model with a front-end modeling the primate primary visual cortex (V1): one sampling RF properties uniformly and the other sampling from empirical biological distributions. The model with the biological sampling has a considerably higher robustness to image corruptions that the uniform variant (relative difference of 8.72%). While similar neuronal sub-populations across the two variants have similar response properties and learn similar downstream weights, the impact on downstream processing is strikingly different. This result sheds light on the origin of the improvements in robustness observed in some biologically-inspired models, pointing to the need of precisely mimicking the neuronal representations found in the primate brain.

Connecting metrics for shape-texture knowledge in computer vision

Jan 25, 2023Abstract:Modern artificial neural networks, including convolutional neural networks and vision transformers, have mastered several computer vision tasks, including object recognition. However, there are many significant differences between the behavior and robustness of these systems and of the human visual system. Deep neural networks remain brittle and susceptible to many changes in the image that do not cause humans to misclassify images. Part of this different behavior may be explained by the type of features humans and deep neural networks use in vision tasks. Humans tend to classify objects according to their shape while deep neural networks seem to rely mostly on texture. Exploring this question is relevant, since it may lead to better performing neural network architectures and to a better understanding of the workings of the vision system of primates. In this work, we advance the state of the art in our understanding of this phenomenon, by extending previous analyses to a much larger set of deep neural network architectures. We found that the performance of models in image classification tasks is highly correlated with their shape bias measured at the output and penultimate layer. Furthermore, our results showed that the number of neurons that represent shape and texture are strongly anti-correlated, thus providing evidence that there is competition between these two types of features. Finally, we observed that while in general there is a correlation between performance and shape bias, there are significant variations between architecture families.

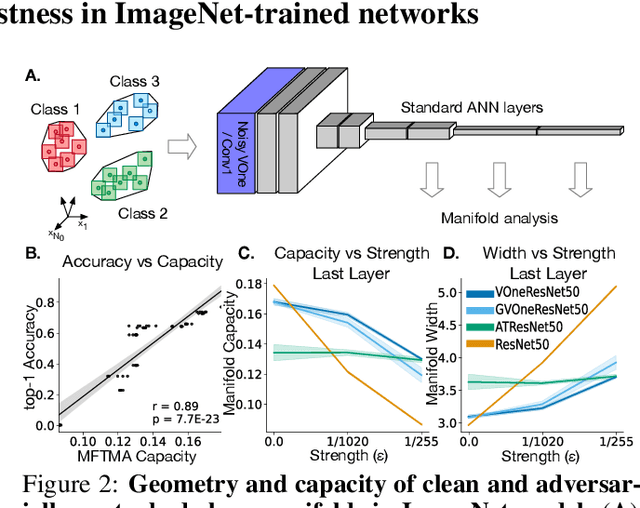

Neural Population Geometry Reveals the Role of Stochasticity in Robust Perception

Nov 12, 2021

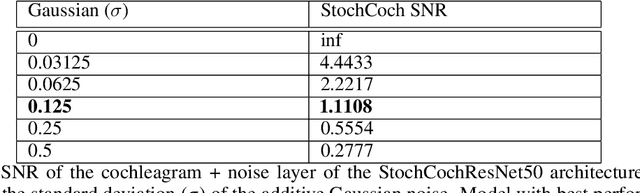

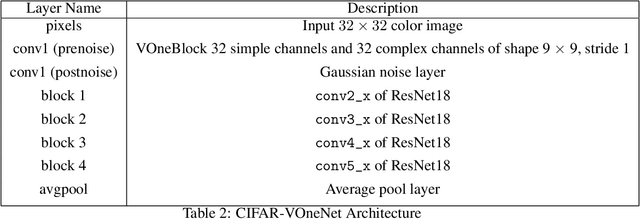

Abstract:Adversarial examples are often cited by neuroscientists and machine learning researchers as an example of how computational models diverge from biological sensory systems. Recent work has proposed adding biologically-inspired components to visual neural networks as a way to improve their adversarial robustness. One surprisingly effective component for reducing adversarial vulnerability is response stochasticity, like that exhibited by biological neurons. Here, using recently developed geometrical techniques from computational neuroscience, we investigate how adversarial perturbations influence the internal representations of standard, adversarially trained, and biologically-inspired stochastic networks. We find distinct geometric signatures for each type of network, revealing different mechanisms for achieving robust representations. Next, we generalize these results to the auditory domain, showing that neural stochasticity also makes auditory models more robust to adversarial perturbations. Geometric analysis of the stochastic networks reveals overlap between representations of clean and adversarially perturbed stimuli, and quantitatively demonstrates that competing geometric effects of stochasticity mediate a tradeoff between adversarial and clean performance. Our results shed light on the strategies of robust perception utilized by adversarially trained and stochastic networks, and help explain how stochasticity may be beneficial to machine and biological computation.

Combining Different V1 Brain Model Variants to Improve Robustness to Image Corruptions in CNNs

Oct 20, 2021

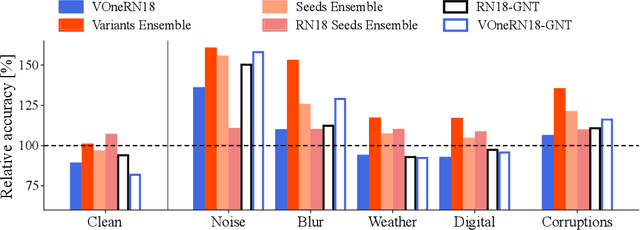

Abstract:While some convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have surpassed human visual abilities in object classification, they often struggle to recognize objects in images corrupted with different types of common noise patterns, highlighting a major limitation of this family of models. Recently, it has been shown that simulating a primary visual cortex (V1) at the front of CNNs leads to small improvements in robustness to these image perturbations. In this study, we start with the observation that different variants of the V1 model show gains for specific corruption types. We then build a new model using an ensembling technique, which combines multiple individual models with different V1 front-end variants. The model ensemble leverages the strengths of each individual model, leading to significant improvements in robustness across all corruption categories and outperforming the base model by 38% on average. Finally, we show that using distillation, it is possible to partially compress the knowledge in the ensemble model into a single model with a V1 front-end. While the ensembling and distillation techniques used here are hardly biologically-plausible, the results presented here demonstrate that by combining the specific strengths of different neuronal circuits in V1 it is possible to improve the robustness of CNNs for a wide range of perturbations.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge