Tania Lombrozo

Fostering Appropriate Reliance on Large Language Models: The Role of Explanations, Sources, and Inconsistencies

Feb 12, 2025

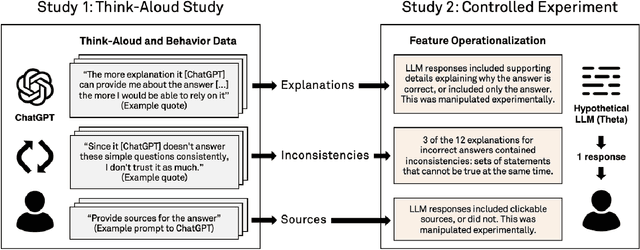

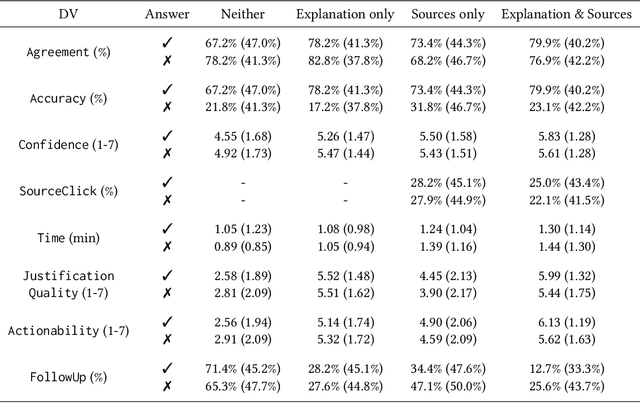

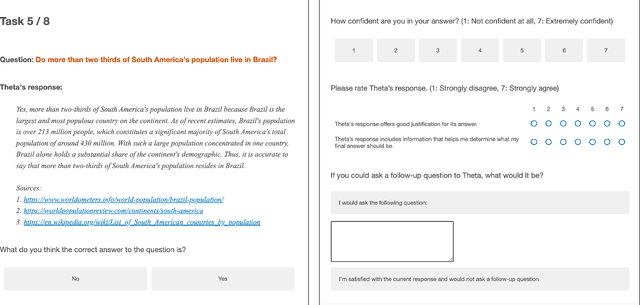

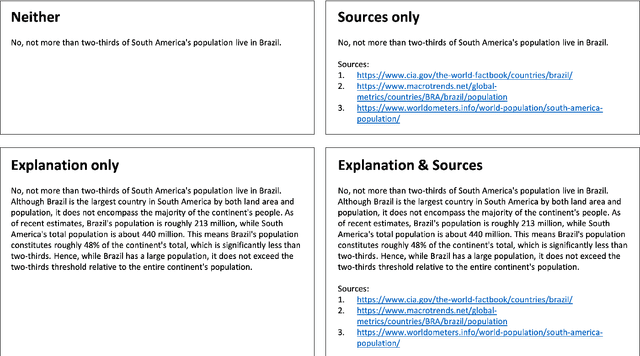

Abstract:Large language models (LLMs) can produce erroneous responses that sound fluent and convincing, raising the risk that users will rely on these responses as if they were correct. Mitigating such overreliance is a key challenge. Through a think-aloud study in which participants use an LLM-infused application to answer objective questions, we identify several features of LLM responses that shape users' reliance: explanations (supporting details for answers), inconsistencies in explanations, and sources. Through a large-scale, pre-registered, controlled experiment (N=308), we isolate and study the effects of these features on users' reliance, accuracy, and other measures. We find that the presence of explanations increases reliance on both correct and incorrect responses. However, we observe less reliance on incorrect responses when sources are provided or when explanations exhibit inconsistencies. We discuss the implications of these findings for fostering appropriate reliance on LLMs.

Mind Your Step (by Step): Chain-of-Thought can Reduce Performance on Tasks where Thinking Makes Humans Worse

Oct 27, 2024Abstract:Chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting has become a widely used strategy for working with large language and multimodal models. While CoT has been shown to improve performance across many tasks, determining the settings in which it is effective remains an ongoing effort. In particular, it is still an open question in what settings CoT systematically reduces model performance. In this paper, we seek to identify the characteristics of tasks where CoT reduces performance by drawing inspiration from cognitive psychology, looking at cases where (i) verbal thinking or deliberation hurts performance in humans, and (ii) the constraints governing human performance generalize to language models. Three such cases are implicit statistical learning, visual recognition, and classifying with patterns containing exceptions. In extensive experiments across all three settings, we find that a diverse collection of state-of-the-art models exhibit significant drop-offs in performance (e.g., up to 36.3% absolute accuracy for OpenAI o1-preview compared to GPT-4o) when using inference-time reasoning compared to zero-shot counterparts. We also identify three tasks that satisfy condition (i) but not (ii), and find that while verbal thinking reduces human performance in these tasks, CoT retains or increases model performance. Overall, our results show that while there is not an exact parallel between the cognitive processes of models and those of humans, considering cases where thinking has negative consequences for human performance can help us identify settings where it negatively impacts models. By connecting the literature on human deliberation with evaluations of CoT, we offer a new tool that can be used in understanding the impact of prompt choices and inference-time reasoning.

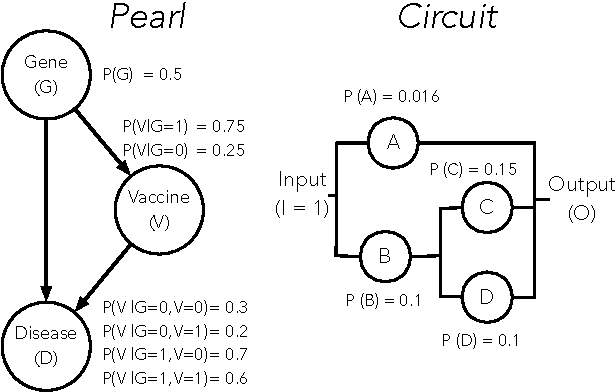

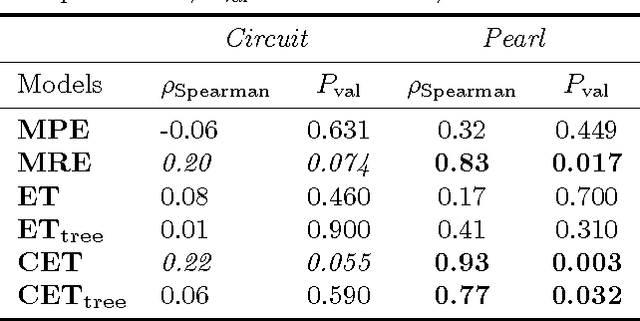

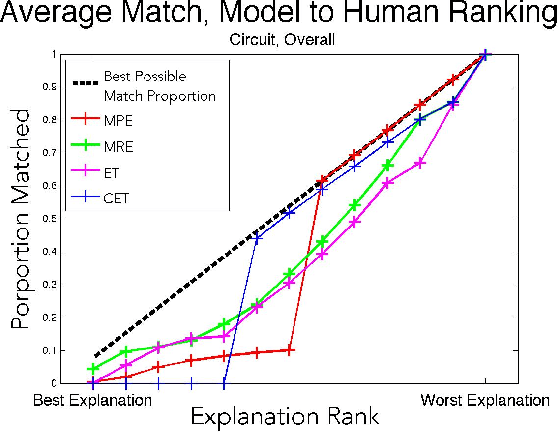

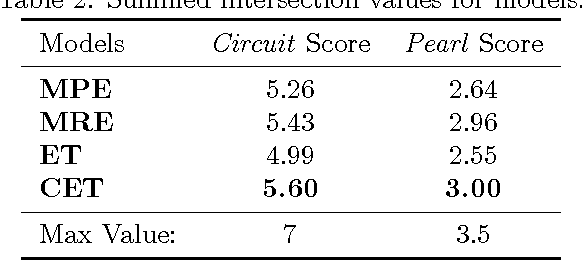

Evaluating computational models of explanation using human judgments

Sep 26, 2013

Abstract:We evaluate four computational models of explanation in Bayesian networks by comparing model predictions to human judgments. In two experiments, we present human participants with causal structures for which the models make divergent predictions and either solicit the best explanation for an observed event (Experiment 1) or have participants rate provided explanations for an observed event (Experiment 2). Across two versions of two causal structures and across both experiments, we find that the Causal Explanation Tree and Most Relevant Explanation models provide better fits to human data than either Most Probable Explanation or Explanation Tree models. We identify strengths and shortcomings of these models and what they can reveal about human explanation. We conclude by suggesting the value of pursuing computational and psychological investigations of explanation in parallel.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge