Markus Plass

Recommendations on test datasets for evaluating AI solutions in pathology

Apr 21, 2022

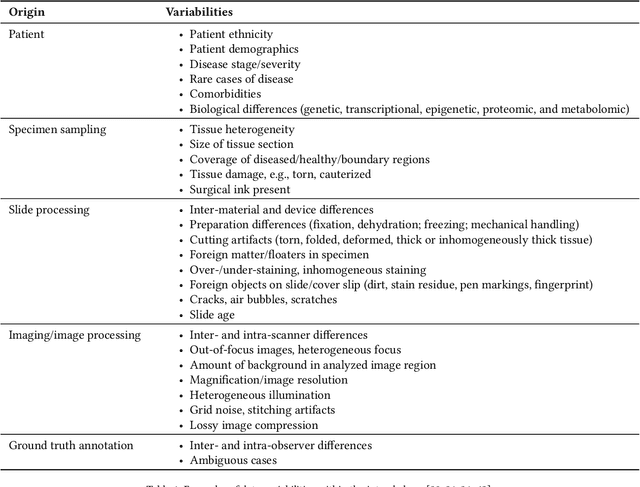

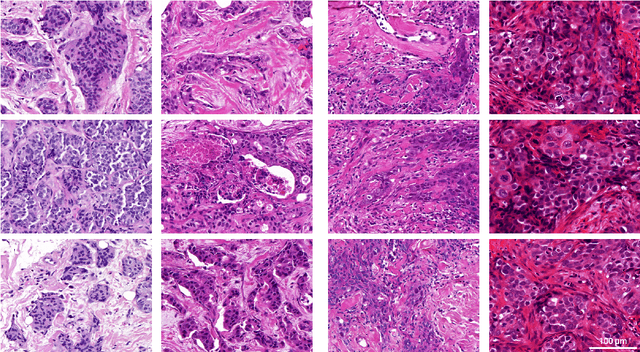

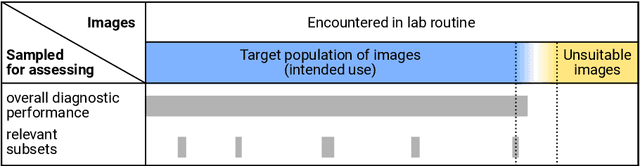

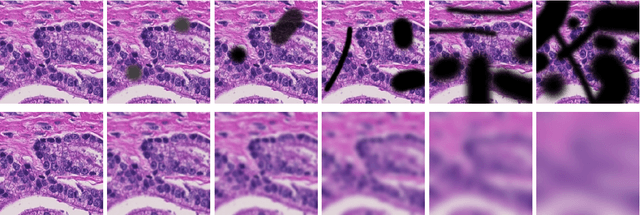

Abstract:Artificial intelligence (AI) solutions that automatically extract information from digital histology images have shown great promise for improving pathological diagnosis. Prior to routine use, it is important to evaluate their predictive performance and obtain regulatory approval. This assessment requires appropriate test datasets. However, compiling such datasets is challenging and specific recommendations are missing. A committee of various stakeholders, including commercial AI developers, pathologists, and researchers, discussed key aspects and conducted extensive literature reviews on test datasets in pathology. Here, we summarize the results and derive general recommendations for the collection of test datasets. We address several questions: Which and how many images are needed? How to deal with low-prevalence subsets? How can potential bias be detected? How should datasets be reported? What are the regulatory requirements in different countries? The recommendations are intended to help AI developers demonstrate the utility of their products and to help regulatory agencies and end users verify reported performance measures. Further research is needed to formulate criteria for sufficiently representative test datasets so that AI solutions can operate with less user intervention and better support diagnostic workflows in the future.

Predicting Prostate Cancer-Specific Mortality with A.I.-based Gleason Grading

Nov 25, 2020

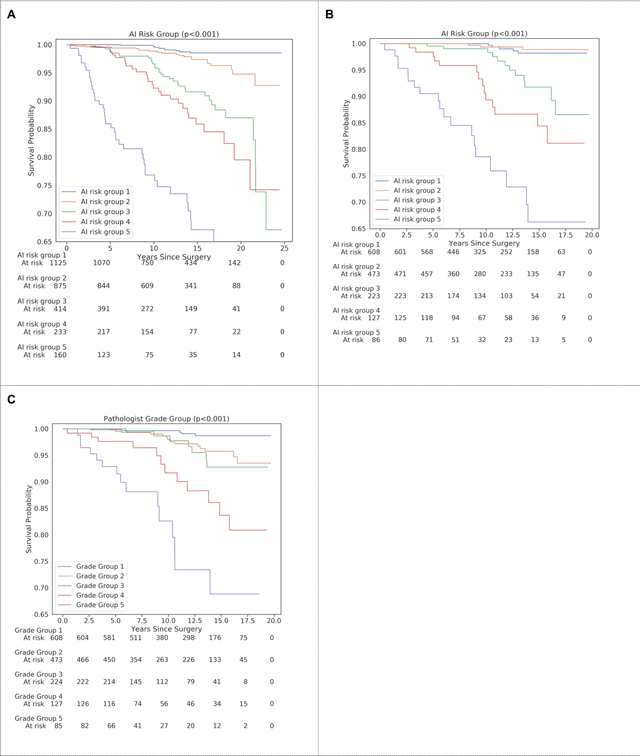

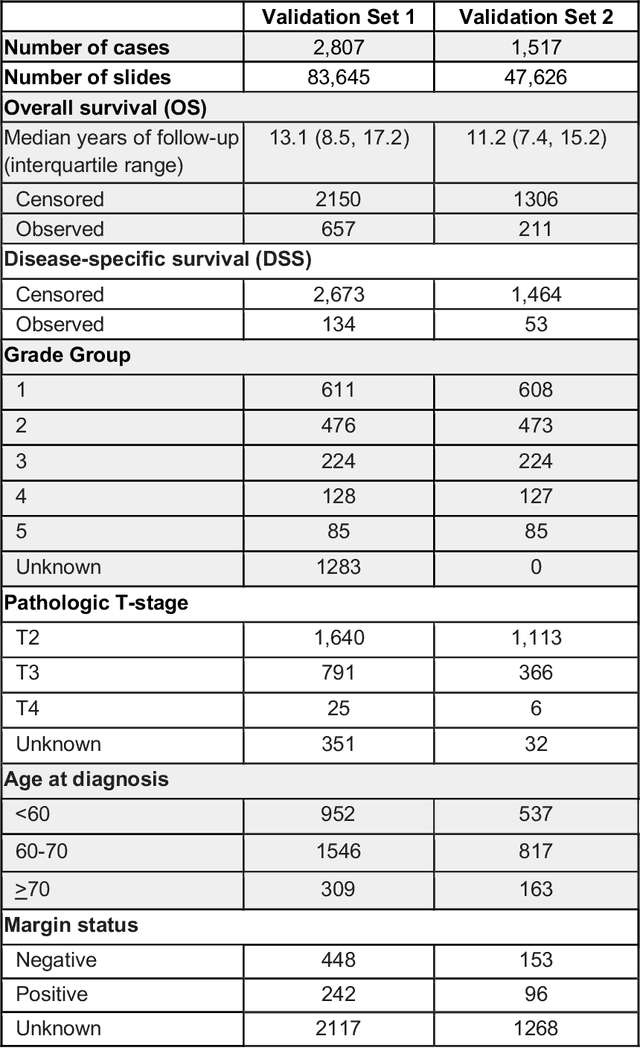

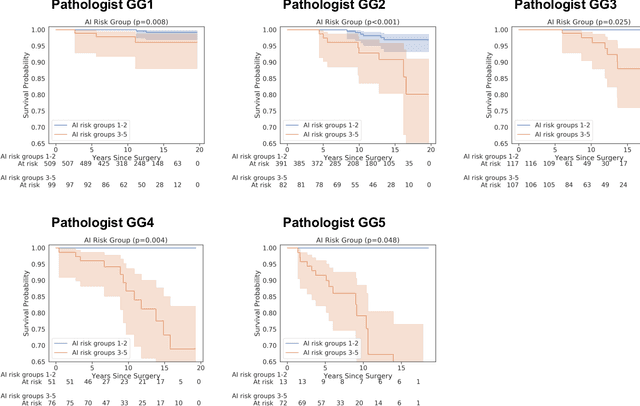

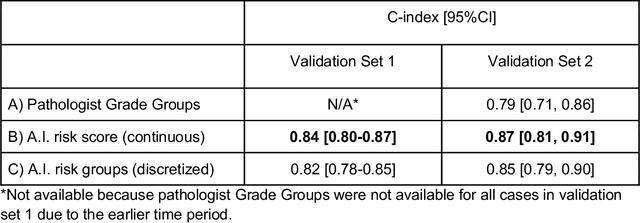

Abstract:Gleason grading of prostate cancer is an important prognostic factor but suffers from poor reproducibility, particularly among non-subspecialist pathologists. Although artificial intelligence (A.I.) tools have demonstrated Gleason grading on-par with expert pathologists, it remains an open question whether A.I. grading translates to better prognostication. In this study, we developed a system to predict prostate-cancer specific mortality via A.I.-based Gleason grading and subsequently evaluated its ability to risk-stratify patients on an independent retrospective cohort of 2,807 prostatectomy cases from a single European center with 5-25 years of follow-up (median: 13, interquartile range 9-17). The A.I.'s risk scores produced a C-index of 0.84 (95%CI 0.80-0.87) for prostate cancer-specific mortality. Upon discretizing these risk scores into risk groups analogous to pathologist Grade Groups (GG), the A.I. had a C-index of 0.82 (95%CI 0.78-0.85). On the subset of cases with a GG in the original pathology report (n=1,517), the A.I.'s C-indices were 0.87 and 0.85 for continuous and discrete grading, respectively, compared to 0.79 (95%CI 0.71-0.86) for GG obtained from the reports. These represent improvements of 0.08 (95%CI 0.01-0.15) and 0.07 (95%CI 0.00-0.14) respectively. Our results suggest that A.I.-based Gleason grading can lead to effective risk-stratification and warrants further evaluation for improving disease management.

Interpretable Survival Prediction for Colorectal Cancer using Deep Learning

Nov 17, 2020

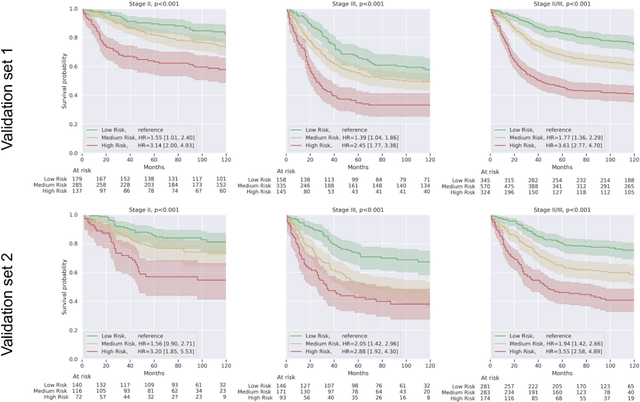

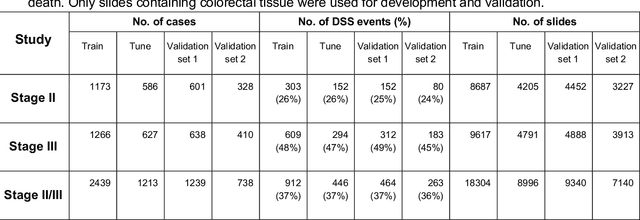

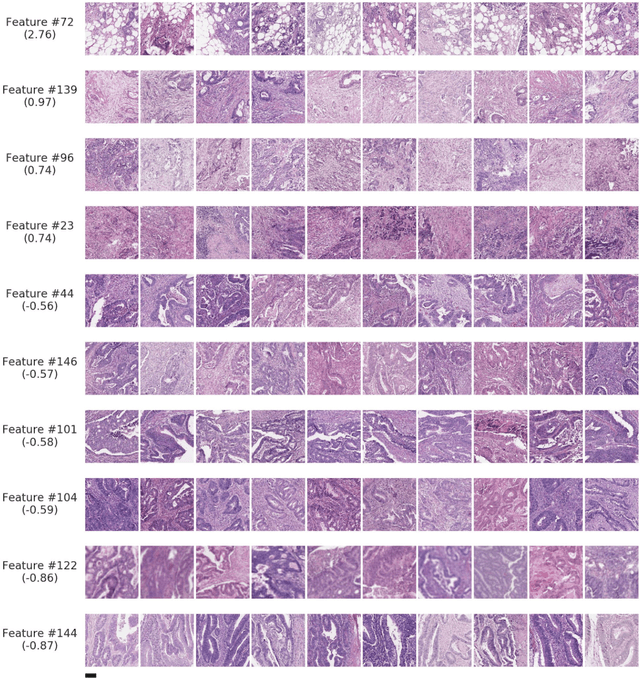

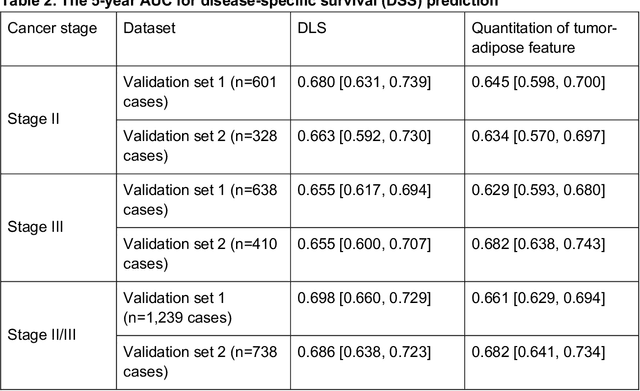

Abstract:Deriving interpretable prognostic features from deep-learning-based prognostic histopathology models remains a challenge. In this study, we developed a deep learning system (DLS) for predicting disease specific survival for stage II and III colorectal cancer using 3,652 cases (27,300 slides). When evaluated on two validation datasets containing 1,239 cases (9,340 slides) and 738 cases (7,140 slides) respectively, the DLS achieved a 5-year disease-specific survival AUC of 0.70 (95%CI 0.66-0.73) and 0.69 (95%CI 0.64-0.72), and added significant predictive value to a set of 9 clinicopathologic features. To interpret the DLS, we explored the ability of different human-interpretable features to explain the variance in DLS scores. We observed that clinicopathologic features such as T-category, N-category, and grade explained a small fraction of the variance in DLS scores (R2=18% in both validation sets). Next, we generated human-interpretable histologic features by clustering embeddings from a deep-learning based image-similarity model and showed that they explain the majority of the variance (R2 of 73% to 80%). Furthermore, the clustering-derived feature most strongly associated with high DLS scores was also highly prognostic in isolation. With a distinct visual appearance (poorly differentiated tumor cell clusters adjacent to adipose tissue), this feature was identified by annotators with 87.0-95.5% accuracy. Our approach can be used to explain predictions from a prognostic deep learning model and uncover potentially-novel prognostic features that can be reliably identified by people for future validation studies.

A glass-box interactive machine learning approach for solving NP-hard problems with the human-in-the-loop

Aug 03, 2017

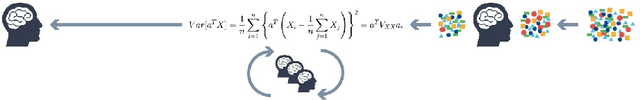

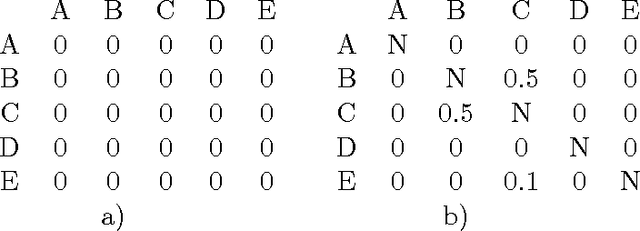

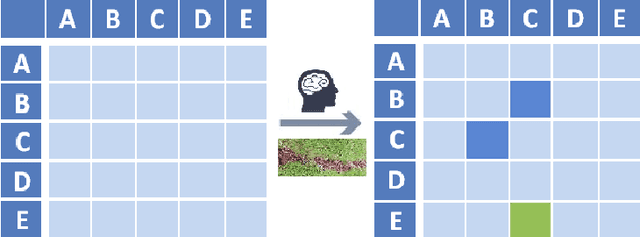

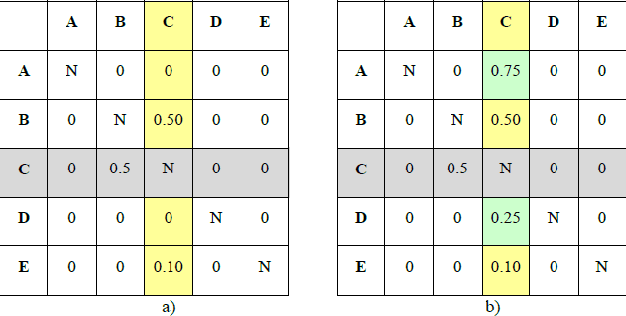

Abstract:The goal of Machine Learning to automatically learn from data, extract knowledge and to make decisions without any human intervention. Such automatic (aML) approaches show impressive success. Recent results even demonstrate intriguingly that deep learning applied for automatic classification of skin lesions is on par with the performance of dermatologists, yet outperforms the average. As human perception is inherently limited, such approaches can discover patterns, e.g. that two objects are similar, in arbitrarily high-dimensional spaces what no human is able to do. Humans can deal only with limited amounts of data, whilst big data is beneficial for aML; however, in health informatics, we are often confronted with a small number of data sets, where aML suffer of insufficient training samples and many problems are computationally hard. Here, interactive machine learning (iML) may be of help, where a human-in-the-loop contributes to reduce the complexity of NP-hard problems. A further motivation for iML is that standard black-box approaches lack transparency, hence do not foster trust and acceptance of ML among end-users. Rising legal and privacy aspects, e.g. with the new European General Data Protection Regulations, make black-box approaches difficult to use, because they often are not able to explain why a decision has been made. In this paper, we present some experiments to demonstrate the effectiveness of the human-in-the-loop approach, particularly in opening the black-box to a glass-box and thus enabling a human directly to interact with an learning algorithm. We selected the Ant Colony Optimization framework, and applied it on the Traveling Salesman Problem, which is a good example, due to its relevance for health informatics, e.g. for the study of protein folding. From studies of how humans extract so much from so little data, fundamental ML-research also may benefit.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge