Judith E Fan

SketchAgent: Language-Driven Sequential Sketch Generation

Nov 26, 2024Abstract:Sketching serves as a versatile tool for externalizing ideas, enabling rapid exploration and visual communication that spans various disciplines. While artificial systems have driven substantial advances in content creation and human-computer interaction, capturing the dynamic and abstract nature of human sketching remains challenging. In this work, we introduce SketchAgent, a language-driven, sequential sketch generation method that enables users to create, modify, and refine sketches through dynamic, conversational interactions. Our approach requires no training or fine-tuning. Instead, we leverage the sequential nature and rich prior knowledge of off-the-shelf multimodal large language models (LLMs). We present an intuitive sketching language, introduced to the model through in-context examples, enabling it to "draw" using string-based actions. These are processed into vector graphics and then rendered to create a sketch on a pixel canvas, which can be accessed again for further tasks. By drawing stroke by stroke, our agent captures the evolving, dynamic qualities intrinsic to sketching. We demonstrate that SketchAgent can generate sketches from diverse prompts, engage in dialogue-driven drawing, and collaborate meaningfully with human users.

Learning Dense Correspondences between Photos and Sketches

Jul 24, 2023Abstract:Humans effortlessly grasp the connection between sketches and real-world objects, even when these sketches are far from realistic. Moreover, human sketch understanding goes beyond categorization -- critically, it also entails understanding how individual elements within a sketch correspond to parts of the physical world it represents. What are the computational ingredients needed to support this ability? Towards answering this question, we make two contributions: first, we introduce a new sketch-photo correspondence benchmark, $\textit{PSC6k}$, containing 150K annotations of 6250 sketch-photo pairs across 125 object categories, augmenting the existing Sketchy dataset with fine-grained correspondence metadata. Second, we propose a self-supervised method for learning dense correspondences between sketch-photo pairs, building upon recent advances in correspondence learning for pairs of photos. Our model uses a spatial transformer network to estimate the warp flow between latent representations of a sketch and photo extracted by a contrastive learning-based ConvNet backbone. We found that this approach outperformed several strong baselines and produced predictions that were quantitatively consistent with other warp-based methods. However, our benchmark also revealed systematic differences between predictions of the suite of models we tested and those of humans. Taken together, our work suggests a promising path towards developing artificial systems that achieve more human-like understanding of visual images at different levels of abstraction. Project page: https://photo-sketch-correspondence.github.io

Physion++: Evaluating Physical Scene Understanding that Requires Online Inference of Different Physical Properties

Jun 27, 2023Abstract:General physical scene understanding requires more than simply localizing and recognizing objects -- it requires knowledge that objects can have different latent properties (e.g., mass or elasticity), and that those properties affect the outcome of physical events. While there has been great progress in physical and video prediction models in recent years, benchmarks to test their performance typically do not require an understanding that objects have individual physical properties, or at best test only those properties that are directly observable (e.g., size or color). This work proposes a novel dataset and benchmark, termed Physion++, that rigorously evaluates visual physical prediction in artificial systems under circumstances where those predictions rely on accurate estimates of the latent physical properties of objects in the scene. Specifically, we test scenarios where accurate prediction relies on estimates of properties such as mass, friction, elasticity, and deformability, and where the values of those properties can only be inferred by observing how objects move and interact with other objects or fluids. We evaluate the performance of a number of state-of-the-art prediction models that span a variety of levels of learning vs. built-in knowledge, and compare that performance to a set of human predictions. We find that models that have been trained using standard regimes and datasets do not spontaneously learn to make inferences about latent properties, but also that models that encode objectness and physical states tend to make better predictions. However, there is still a huge gap between all models and human performance, and all models' predictions correlate poorly with those made by humans, suggesting that no state-of-the-art model is learning to make physical predictions in a human-like way. Project page: https://dingmyu.github.io/physion_v2/

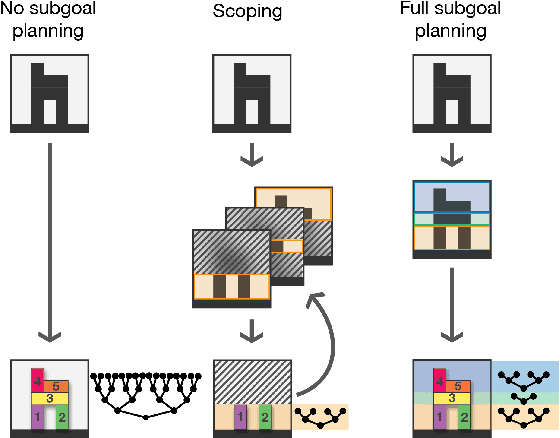

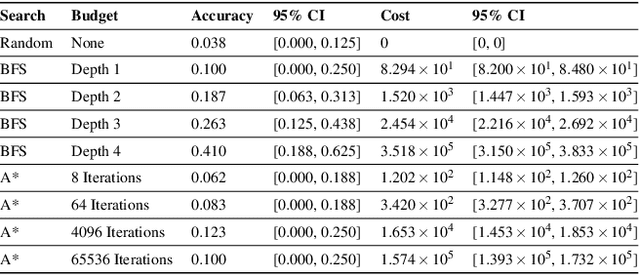

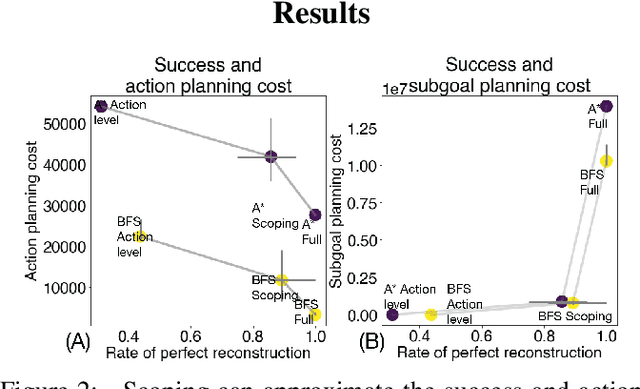

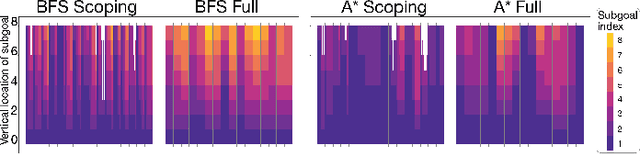

Visual scoping operations for physical assembly

Jun 10, 2021

Abstract:Planning is hard. The use of subgoals can make planning more tractable, but selecting these subgoals is computationally costly. What algorithms might enable us to reap the benefits of planning using subgoals while minimizing the computational overhead of selecting them? We propose visual scoping, a strategy that interleaves planning and acting by alternately defining a spatial region as the next subgoal and selecting actions to achieve it. We evaluated our visual scoping algorithm on a variety of physical assembly problems against two baselines: planning all subgoals in advance and planning without subgoals. We found that visual scoping achieves comparable task performance to the subgoal planner while requiring only a fraction of the total computational cost. Together, these results contribute to our understanding of how humans might make efficient use of cognitive resources to solve complex planning problems.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge