Li-Ching Chen

Dynamical Regimes of Multimodal Diffusion Models

Feb 04, 2026Abstract:Diffusion based generative models have achieved unprecedented fidelity in synthesizing high dimensional data, yet the theoretical mechanisms governing multimodal generation remain poorly understood. Here, we present a theoretical framework for coupled diffusion models, using coupled Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes as a tractable model. By using the nonequilibrium statistical physics of dynamical phase transitions, we demonstrate that multimodal generation is governed by a spectral hierarchy of interaction timescales rather than simultaneous resolution. A key prediction is the ``synchronization gap'', a temporal window during the reverse generative process where distinct eigenmodes stabilize at different rates, providing a theoretical explanation for common desynchronization artifacts. We derive analytical conditions for speciation and collapse times under both symmetric and anisotropic coupling regimes, establishing strict bounds for coupling strength to avoid unstable symmetry breaking. We show that the coupling strength acts as a spectral filter that enforces a tunable temporal hierarchy on generation. We support these predictions through controlled experiments with diffusion models trained on MNIST datasets and exact score samplers. These results motivate time dependent coupling schedules that target mode specific timescales, offering a potential alternative to ad hoc guidance tuning.

Early Diagnosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease from Chest X-Rays using Transfer Learning and Fusion Strategies

Nov 13, 2022Abstract:Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the most common chronic illnesses in the world and the third leading cause of mortality worldwide. It is often underdiagnosed or not diagnosed until later in the disease course. Spirometry tests are the gold standard for diagnosing COPD but can be difficult to obtain, especially in resource-poor countries. Chest X-rays (CXRs), however, are readily available and may serve as a screening tool to identify patients with COPD who should undergo further testing. Currently, no research applies deep learning (DL) algorithms that use large multi-site and multi-modal data to detect COPD patients and evaluate fairness across demographic groups. We use three CXR datasets in our study, CheXpert to pre-train models, MIMIC-CXR to develop, and Emory-CXR to validate our models. The CXRs from patients in the early stage of COPD and not on mechanical ventilation are selected for model training and validation. We visualize the Grad-CAM heatmaps of the true positive cases on the base model for both MIMIC-CXR and Emory-CXR test datasets. We further propose two fusion schemes, (1) model-level fusion, including bagging and stacking methods using MIMIC-CXR, and (2) data-level fusion, including multi-site data using MIMIC-CXR and Emory-CXR, and multi-modal using MIMIC-CXRs and MIMIC-IV EHR, to improve the overall model performance. Fairness analysis is performed to evaluate if the fusion schemes have a discrepancy in the performance among different demographic groups. The results demonstrate that DL models can detect COPD using CXRs, which can facilitate early screening, especially in low-resource regions where CXRs are more accessible than spirometry. The multi-site data fusion scheme could improve the model generalizability on the Emory-CXR test data. Further studies on using CXR or other modalities to predict COPD ought to be in future work.

Reading Race: AI Recognises Patient's Racial Identity In Medical Images

Jul 21, 2021

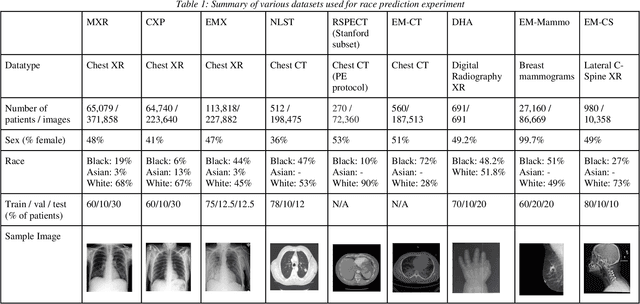

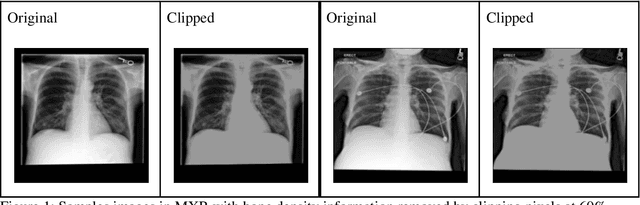

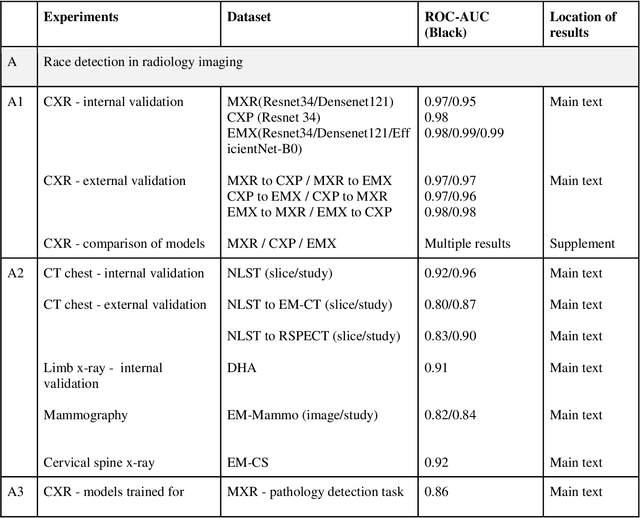

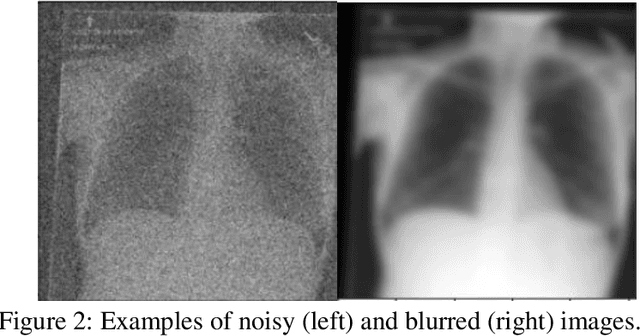

Abstract:Background: In medical imaging, prior studies have demonstrated disparate AI performance by race, yet there is no known correlation for race on medical imaging that would be obvious to the human expert interpreting the images. Methods: Using private and public datasets we evaluate: A) performance quantification of deep learning models to detect race from medical images, including the ability of these models to generalize to external environments and across multiple imaging modalities, B) assessment of possible confounding anatomic and phenotype population features, such as disease distribution and body habitus as predictors of race, and C) investigation into the underlying mechanism by which AI models can recognize race. Findings: Standard deep learning models can be trained to predict race from medical images with high performance across multiple imaging modalities. Our findings hold under external validation conditions, as well as when models are optimized to perform clinically motivated tasks. We demonstrate this detection is not due to trivial proxies or imaging-related surrogate covariates for race, such as underlying disease distribution. Finally, we show that performance persists over all anatomical regions and frequency spectrum of the images suggesting that mitigation efforts will be challenging and demand further study. Interpretation: We emphasize that model ability to predict self-reported race is itself not the issue of importance. However, our findings that AI can trivially predict self-reported race -- even from corrupted, cropped, and noised medical images -- in a setting where clinical experts cannot, creates an enormous risk for all model deployments in medical imaging: if an AI model secretly used its knowledge of self-reported race to misclassify all Black patients, radiologists would not be able to tell using the same data the model has access to.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge