Johannes Eichstaedt

Empathic Conversations: A Multi-level Dataset of Contextualized Conversations

May 25, 2022

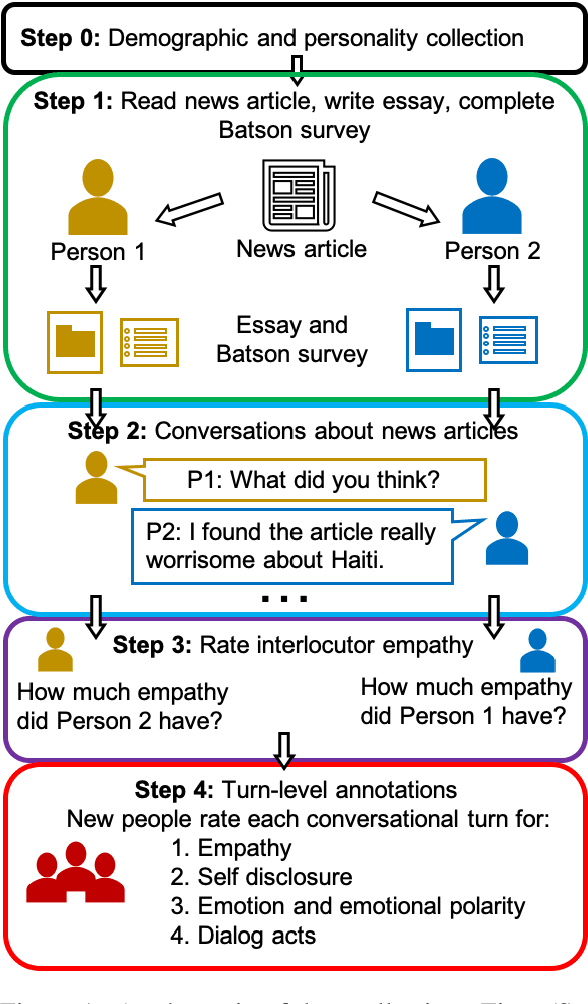

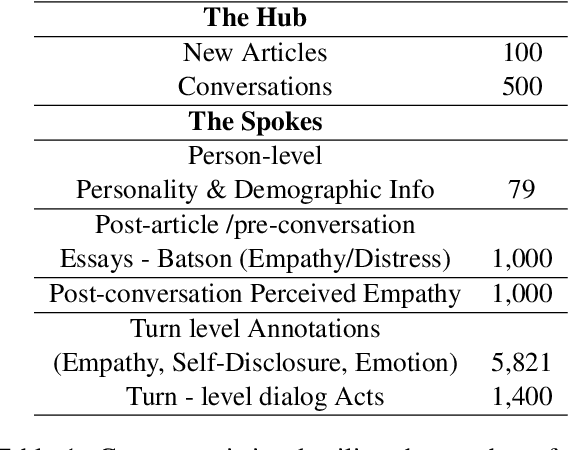

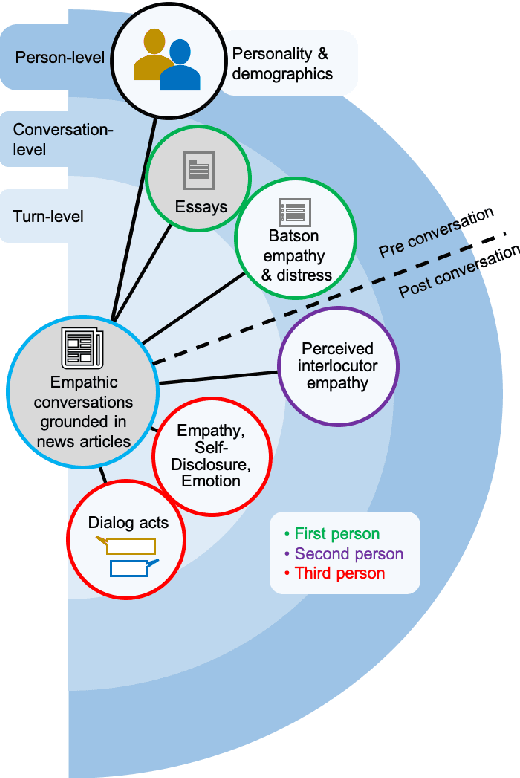

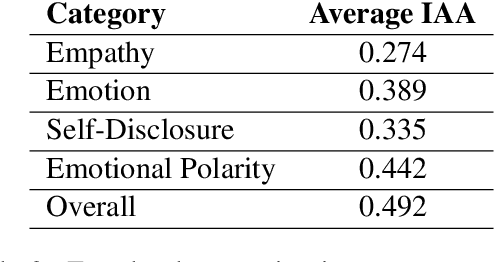

Abstract:Empathy is a cognitive and emotional reaction to an observed situation of others. Empathy has recently attracted interest because it has numerous applications in psychology and AI, but it is unclear how different forms of empathy (e.g., self-report vs counterpart other-report, concern vs. distress) interact with other affective phenomena or demographics like gender and age. To better understand this, we created the {\it Empathic Conversations} dataset of annotated negative, empathy-eliciting dialogues in which pairs of participants converse about news articles. People differ in their perception of the empathy of others. These differences are associated with certain characteristics such as personality and demographics. Hence, we collected detailed characterization of the participants' traits, their self-reported empathetic response to news articles, their conversational partner other-report, and turn-by-turn third-party assessments of the level of self-disclosure, emotion, and empathy expressed. This dataset is the first to present empathy in multiple forms along with personal distress, emotion, personality characteristics, and person-level demographic information. We present baseline models for predicting some of these features from conversations.

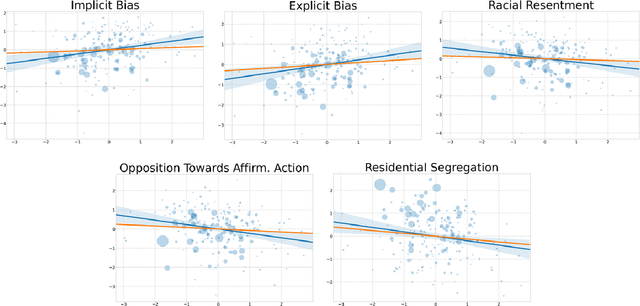

Regional Negative Bias in Word Embeddings Predicts Racial Animus--but only via Name Frequency

Jan 20, 2022

Abstract:The word embedding association test (WEAT) is an important method for measuring linguistic biases against social groups such as ethnic minorities in large text corpora. It does so by comparing the semantic relatedness of words prototypical of the groups (e.g., names unique to those groups) and attribute words (e.g., 'pleasant' and 'unpleasant' words). We show that anti-black WEAT estimates from geo-tagged social media data at the level of metropolitan statistical areas strongly correlate with several measures of racial animus--even when controlling for sociodemographic covariates. However, we also show that every one of these correlations is explained by a third variable: the frequency of Black names in the underlying corpora relative to White names. This occurs because word embeddings tend to group positive (negative) words and frequent (rare) words together in the estimated semantic space. As the frequency of Black names on social media is strongly correlated with Black Americans' prevalence in the population, this results in spurious anti-Black WEAT estimates wherever few Black Americans live. This suggests that research using the WEAT to measure bias should consider term frequency, and also demonstrates the potential consequences of using black-box models like word embeddings to study human cognition and behavior.

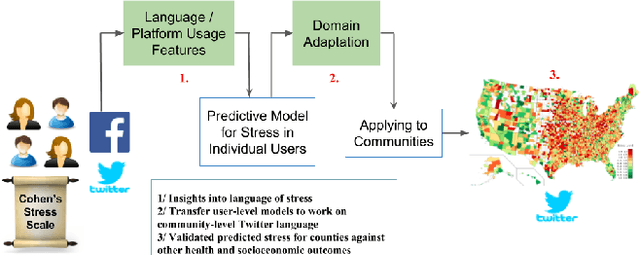

Understanding and Measuring Psychological Stress using Social Media

Nov 19, 2018

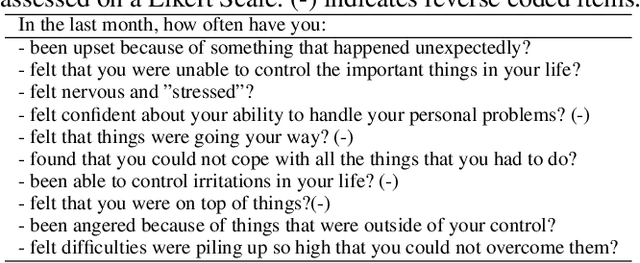

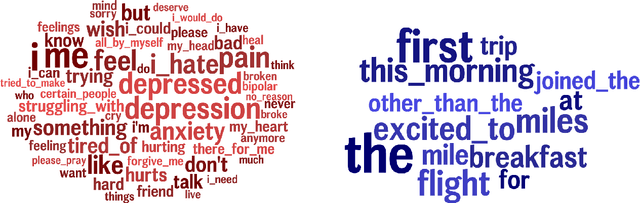

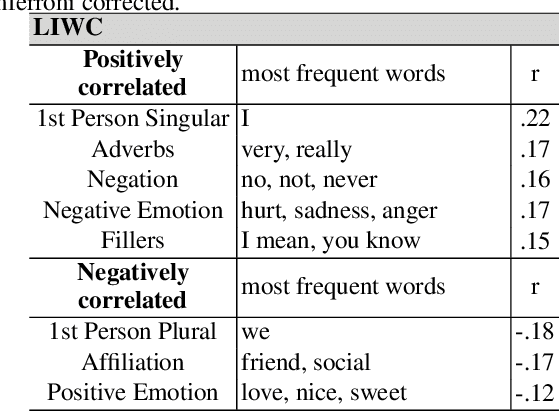

Abstract:A body of literature has demonstrated that users' mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, can be predicted from their social media language. There is still a gap in the scientific understanding of how psychological stress is expressed on social media. Stress is one of the primary underlying causes and correlates of chronic physical illnesses and mental health conditions. In this paper, we explore the language of psychological stress with a dataset of 601 social media users, who answered the Perceived Stress Scale questionnaire and also consented to share their Facebook and Twitter data. Firstly, we find that stressed users post about exhaustion, losing control, increased self-focus and physical pain as compared to posts about breakfast, family-time, and travel by users who are not stressed. Secondly, we find that Facebook language is more predictive of stress than Twitter language. Thirdly, we demonstrate how the language based models thus developed can be adapted and be scaled to measure county-level trends. Since county-level language is easily available on Twitter using the Streaming API, we explore multiple domain adaptation algorithms to adapt user-level Facebook models to Twitter language. We find that domain-adapted and scaled social media-based measurements of stress outperform sociodemographic variables (age, gender, race, education, and income), against ground-truth survey-based stress measurements, both at the user- and the county-level in the U.S. Twitter language that scores higher in stress is also predictive of poorer health, less access to facilities and lower socioeconomic status in counties. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of using social media as a new tool for monitoring stress levels of both individuals and counties.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge