Simon DeDeo

From "um" to "yeah": Producing, predicting, and regulating information flow in human conversation

Mar 13, 2024

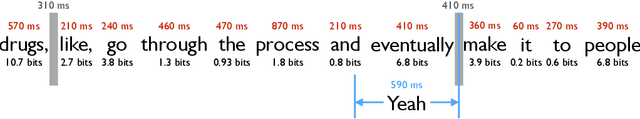

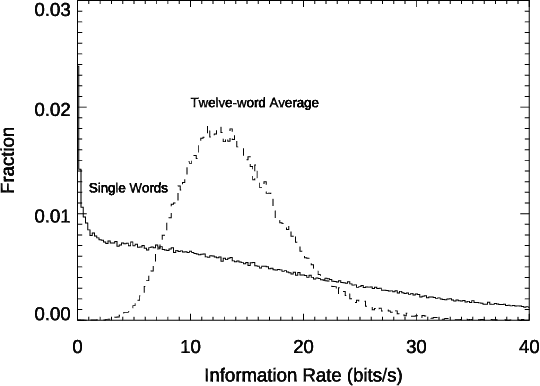

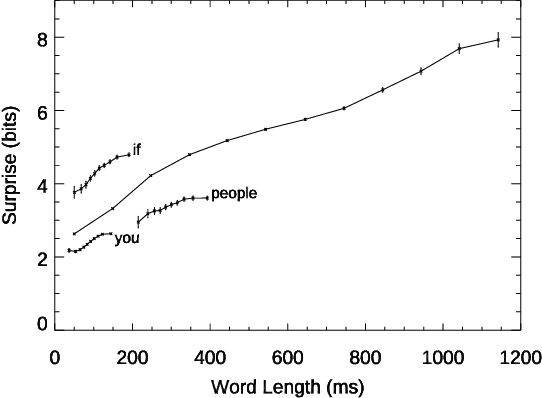

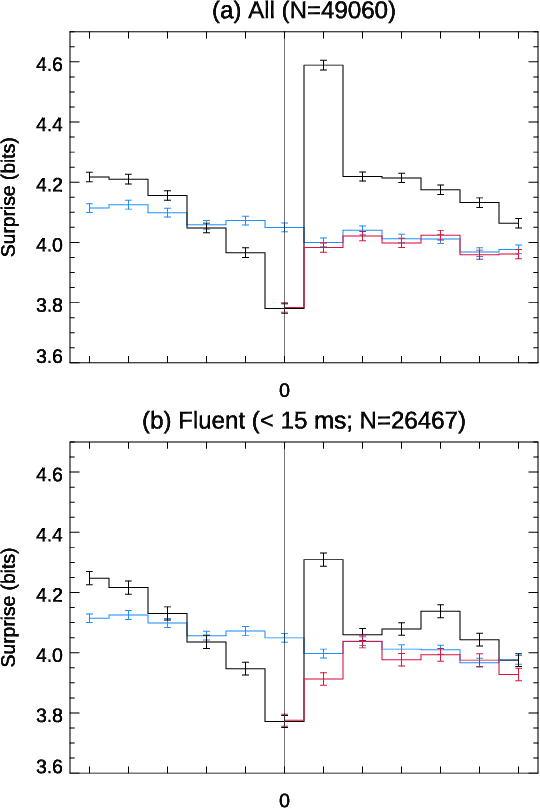

Abstract:Conversation demands attention. Speakers must call words to mind, listeners must make sense of them, and both together must negotiate this flow of information, all in fractions of a second. We used large language models to study how this works in a large-scale dataset of English-language conversation, the CANDOR corpus. We provide a new estimate of the information density of unstructured conversation, of approximately 13 bits/second, and find significant effects associated with the cognitive load of both retrieving, and presenting, that information. We also reveal a role for backchannels -- the brief yeahs, uh-huhs, and mhmms that listeners provide -- in regulating the production of novelty: the lead-up to a backchannel is associated with declining information rate, while speech downstream rebounds to previous rates. Our results provide new insights into long-standing theories of how we respond to fluctuating demands on cognitive resources, and how we negotiate those demands in partnership with others.

The Diversity of Argument-Making in the Wild: from Assumptions and Definitions to Causation and Anecdote in Reddit's "Change My View"

May 16, 2022

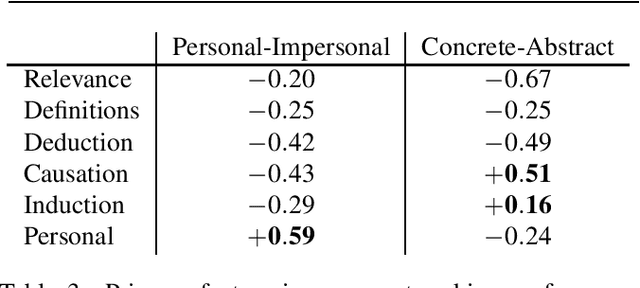

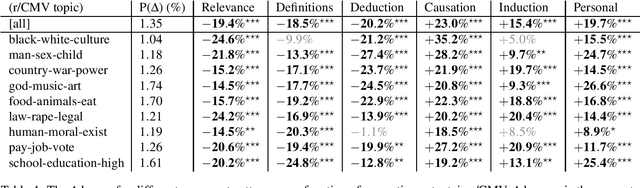

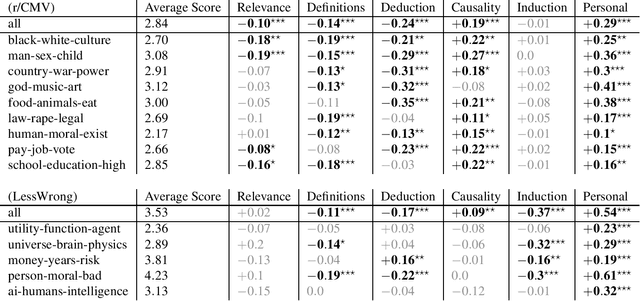

Abstract:What kinds of arguments do people make, and what effect do they have on others? Normative constraints on argument-making are as old as philosophy itself, but little is known about the diversity of arguments made in practice. We use NLP tools to extract patterns of argument-making from the Reddit site "Change My View" (r/CMV). This reveals six distinct argument patterns: not just the familiar deductive and inductive forms, but also arguments about definitions, relevance, possibility and cause, and personal experience. Data from r/CMV also reveal differences in efficacy: personal experience and, to a lesser extent, arguments about causation and examples, are most likely to shift a person's view, while arguments about relevance are the least. Finally, our methods reveal a gradient of argument-making preferences among users: a two-axis model, of "personal--impersonal" and "concrete--abstract", can account for nearly 80% of the strategy variance between individuals.

From Probability to Consilience: How Explanatory Values Implement Bayesian Reasoning

Jun 03, 2020

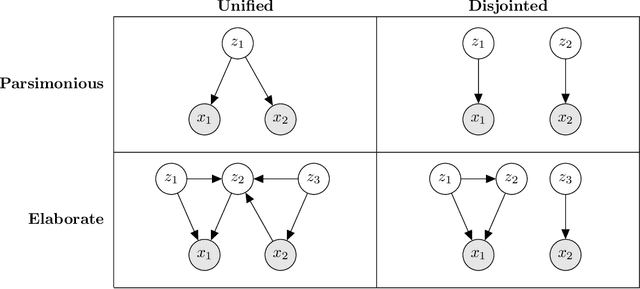

Abstract:Recent work in cognitive science has uncovered a diversity of explanatory values, or dimensions along which we judge explanations as better or worse. We propose a Bayesian account of how these values fit together to guide explanation. The resulting taxonomy provides a set of predictors for which explanations people prefer and shows how core values from psychology, statistics, and the philosophy of science emerge from a common mathematical framework. In addition to operationalizing the explanatory virtues associated with, for example, scientific argument-making, this framework also enables us to reinterpret the explanatory vices that drive conspiracy theories, delusions, and extremist ideologies.

Explosive Proofs of Mathematical Truths

Mar 31, 2020

Abstract:Mathematical proofs are both paradigms of certainty and some of the most explicitly-justified arguments that we have in the cultural record. Their very explicitness, however, leads to a paradox, because their probability of error grows exponentially as the argument expands. Here we show that under a cognitively-plausible belief formation mechanism that combines deductive and abductive reasoning, mathematical arguments can undergo what we call an epistemic phase transition: a dramatic and rapidly-propagating jump from uncertainty to near-complete confidence at reasonable levels of claim-to-claim error rates. To show this, we analyze an unusual dataset of forty-eight machine-aided proofs from the formalized reasoning system Coq, including major theorems ranging from ancient to 21st Century mathematics, along with four hand-constructed cases from Euclid, Apollonius, Spinoza, and Andrew Wiles. Our results bear both on recent work in the history and philosophy of mathematics, and on a question, basic to cognitive science, of how we form beliefs, and justify them to others.

How we do things with words: Analyzing text as social and cultural data

Jul 02, 2019Abstract:In this article we describe our experiences with computational text analysis. We hope to achieve three primary goals. First, we aim to shed light on thorny issues not always at the forefront of discussions about computational text analysis methods. Second, we hope to provide a set of best practices for working with thick social and cultural concepts. Our guidance is based on our own experiences and is therefore inherently imperfect. Still, given our diversity of disciplinary backgrounds and research practices, we hope to capture a range of ideas and identify commonalities that will resonate for many. And this leads to our final goal: to help promote interdisciplinary collaborations. Interdisciplinary insights and partnerships are essential for realizing the full potential of any computational text analysis that involves social and cultural concepts, and the more we are able to bridge these divides, the more fruitful we believe our work will be.

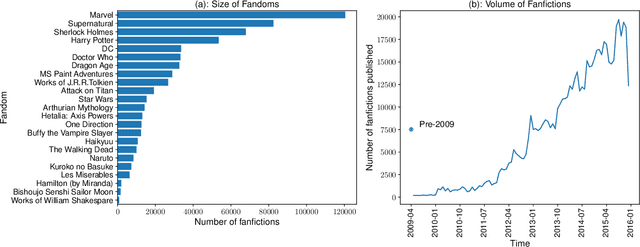

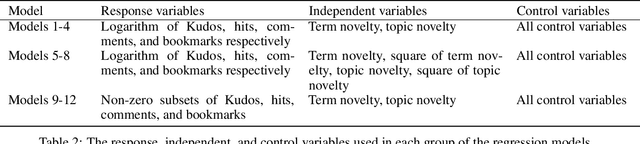

Sameness Attracts, Novelty Disturbs, but Outliers Flourish in Fanfiction Online

Apr 16, 2019

Abstract:The nature of what people enjoy is not just a central question for the creative industry, it is a driving force of cultural evolution. It is widely believed that successful cultural products balance novelty and conventionality: they provide something familiar but at least somewhat divergent from what has come before, and occupy a satisfying middle ground between "more of the same" and "too strange". We test this belief using a large dataset of over half a million works of fanfiction from the website Archive of Our Own (AO3), looking at how the recognition a work receives varies with its novelty. We quantify the novelty through a term-based language model, and a topic model, in the context of existing works within the same fandom. Contrary to the balance theory, we find that the lowest-novelty are the most popular and that popularity declines monotonically with novelty. A few exceptions can be found: extremely popular works that are among the highest novelty within the fandom. Taken together, our findings not only challenge the traditional theory of the hedonic value of novelty, they invert it: people prefer the least novel things, are repelled by the middle ground, and have an occasional enthusiasm for extreme outliers. It suggests that cultural evolution must work against inertia --- the appetite people have to continually reconsume the familiar, and may resemble a punctuated equilibrium rather than a smooth evolution.

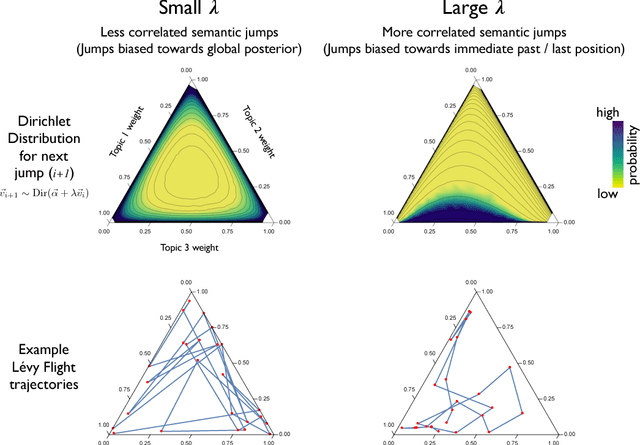

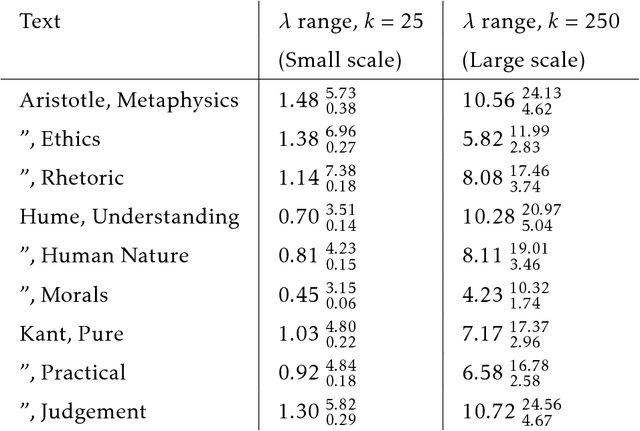

Lévy Flights of the Collective Imagination

Dec 10, 2018

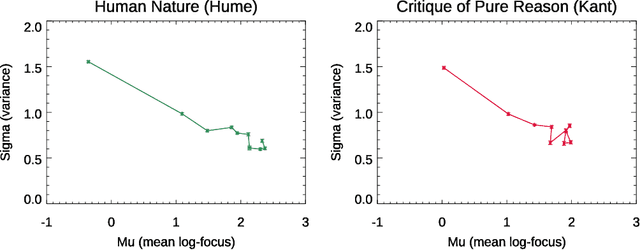

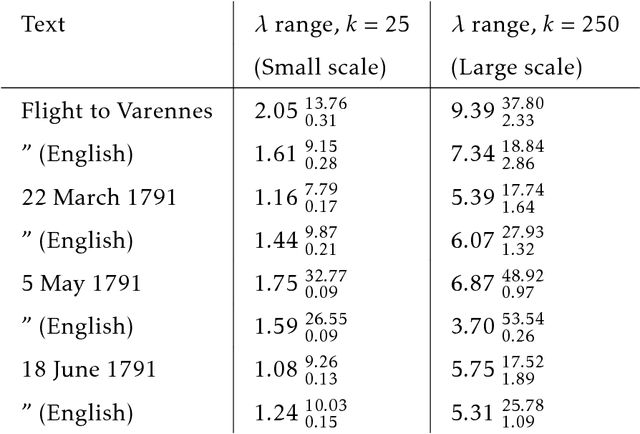

Abstract:We present a structured random-walk model that captures key aspects of how people communicate in groups. Our model takes the form of a correlated L\'{e}vy flight that quantifies the balance between focused discussion of an idea and long-distance leaps in semantic space. We apply our model to three cases of increasing structural complexity: philosophical texts by Aristotle, Hume, and Kant; four days of parliamentary debate during the French Revolution; and branching comment trees on the discussion website Reddit. In the philosophical and parliamentary cases, the model parameters that describe this balance converge under coarse-graining to limit regions that demonstrate the emergence of large-scale structure, a result which is robust to translation between languages. Meanwhile, we find that the political forum we consider on Reddit exhibits a debate-like pattern, while communities dedicated to the discussion of science and news show much less temporal order, and may make use of the emergent, tree-like topology of comment replies to structure their epistemic explorations. Our model allows us to quantify the ways in which social technologies such as parliamentary procedures and online commenting systems shape the joint exploration of ideas.

Opacity, Obscurity, and the Geometry of Question-Asking

Sep 21, 2018

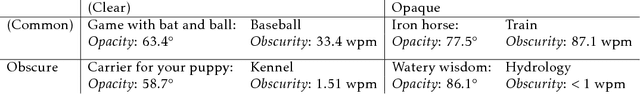

Abstract:Asking questions is a pervasive human activity, but little is understood about what makes them difficult to answer. An analysis of a pair of large databases, of New York Times crosswords and questions from the quiz-show Jeopardy, establishes two orthogonal dimensions of question difficulty: obscurity (the rarity of the answer) and opacity (the indirectness of question cues, operationalized with word2vec). The importance of opacity, and the role of synergistic information in resolving it, suggests that accounts of difficulty in terms of prior expectations captures only a part of the question-asking process. A further regression analysis shows the presence of additional dimensions to question-asking: question complexity, the answer's local network density, cue intersection, and the presence of signal words. Our work shows how question-askers can help their interlocutors by using contextual cues, or, conversely, how a particular kind of unfamiliarity with the domain in question can make it harder for individuals to learn from others. Taken together, these results suggest how Bayesian models of question difficulty can be supplemented by process models and accounts of the heuristics individuals use to navigate conceptual spaces.

The Development of Darwin's Origin of Species

Feb 26, 2018

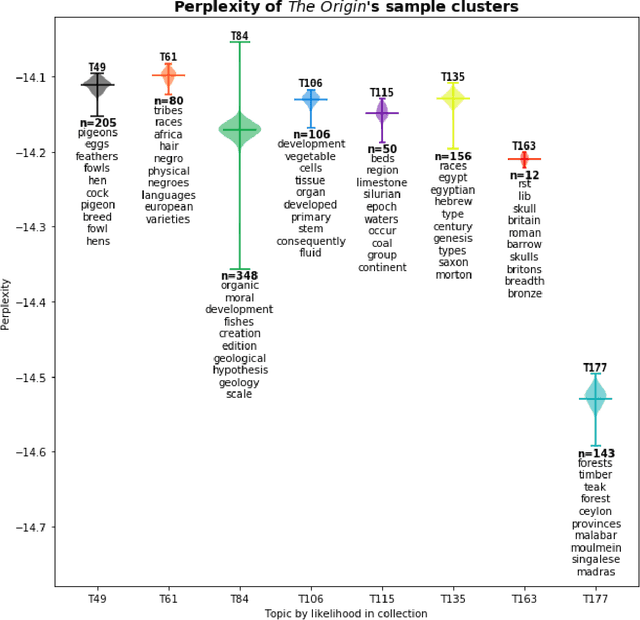

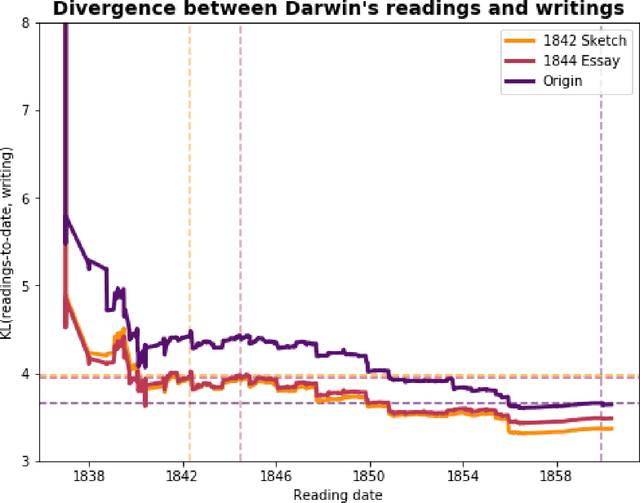

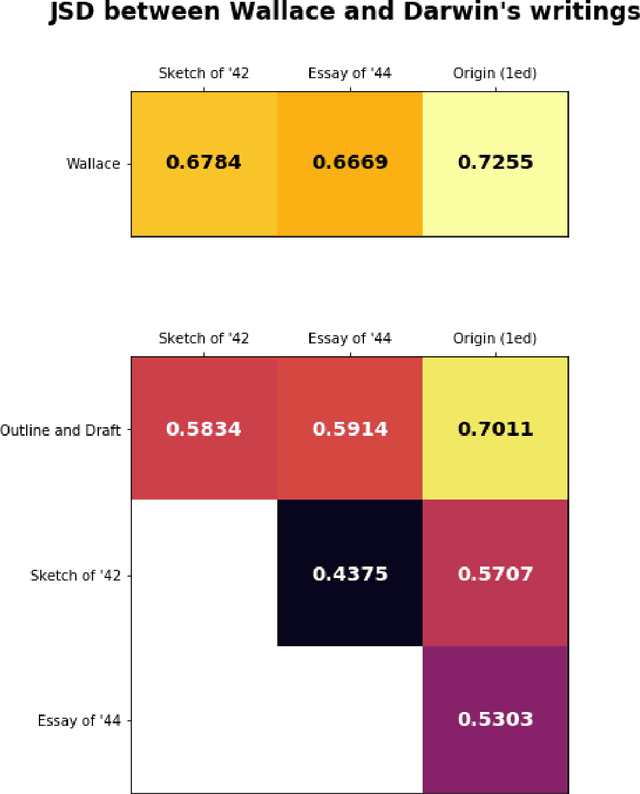

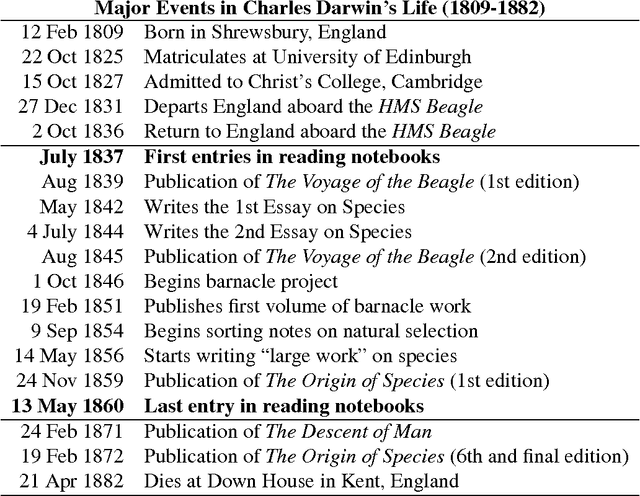

Abstract:From 1837, when he returned to England aboard the $\textit{HMS Beagle}$, to 1860, just after publication of $\textit{The Origin of Species}$, Charles Darwin kept detailed notes of each book he read or wanted to read. His notes and manuscripts provide information about decades of individual scientific practice. Previously, we trained topic models on the full texts of each reading, and applied information-theoretic measures to detect that changes in his reading patterns coincided with the boundaries of his three major intellectual projects in the period 1837-1860. In this new work we apply the reading model to five additional documents, four of them by Darwin: the first edition of $\textit{The Origin of Species}$, two private essays stating intermediate forms of his theory in 1842 and 1844, a third essay of disputed dating, and Alfred Russel Wallace's essay, which Darwin received in 1858. We address three historical inquiries, previously treated qualitatively: 1) the mythology of "Darwin's Delay," that despite completing an extensive draft in 1844, Darwin waited until 1859 to publish $\textit{The Origin of Species}$ due to external pressures; 2) the relationship between Darwin and Wallace's contemporaneous theories, especially in light of their joint presentation; and 3) dating of the "Outline and Draft" which was rediscovered in 1975 and postulated first as an 1839 draft preceding the Sketch of 1842, then as an interstitial draft between the 1842 and 1844 essays.

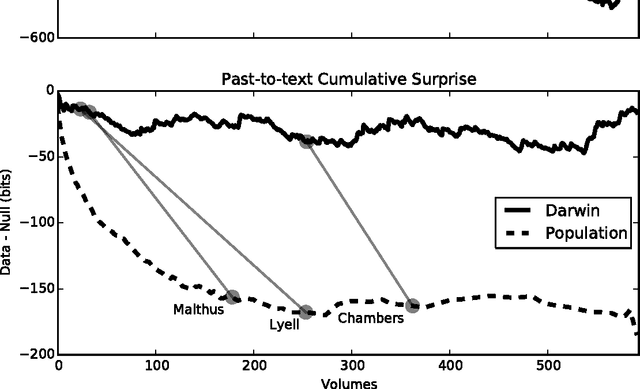

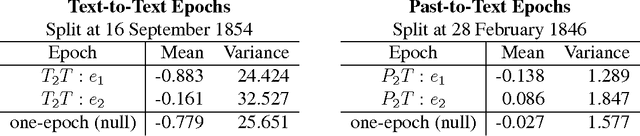

Exploration and Exploitation of Victorian Science in Darwin's Reading Notebooks

Feb 02, 2017

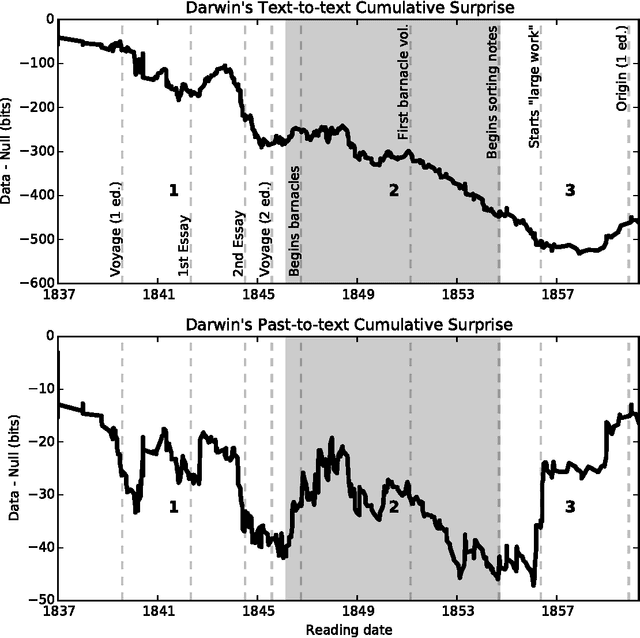

Abstract:Search in an environment with an uncertain distribution of resources involves a trade-off between exploitation of past discoveries and further exploration. This extends to information foraging, where a knowledge-seeker shifts between reading in depth and studying new domains. To study this decision-making process, we examine the reading choices made by one of the most celebrated scientists of the modern era: Charles Darwin. From the full-text of books listed in his chronologically-organized reading journals, we generate topic models to quantify his local (text-to-text) and global (text-to-past) reading decisions using Kullback-Liebler Divergence, a cognitively-validated, information-theoretic measure of relative surprise. Rather than a pattern of surprise-minimization, corresponding to a pure exploitation strategy, Darwin's behavior shifts from early exploitation to later exploration, seeking unusually high levels of cognitive surprise relative to previous eras. These shifts, detected by an unsupervised Bayesian model, correlate with major intellectual epochs of his career as identified both by qualitative scholarship and Darwin's own self-commentary. Our methods allow us to compare his consumption of texts with their publication order. We find Darwin's consumption more exploratory than the culture's production, suggesting that underneath gradual societal changes are the explorations of individual synthesis and discovery. Our quantitative methods advance the study of cognitive search through a framework for testing interactions between individual and collective behavior and between short- and long-term consumption choices. This novel application of topic modeling to characterize individual reading complements widespread studies of collective scientific behavior.

* Cognition pre-print, published February 2017; 22 pages, plus 17 pages supporting information, 7 pages references

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge