Gonzalo Martínez

Adding LLMs to the psycholinguistic norming toolbox: A practical guide to getting the most out of human ratings

Sep 17, 2025Abstract:Word-level psycholinguistic norms lend empirical support to theories of language processing. However, obtaining such human-based measures is not always feasible or straightforward. One promising approach is to augment human norming datasets by using Large Language Models (LLMs) to predict these characteristics directly, a practice that is rapidly gaining popularity in psycholinguistics and cognitive science. However, the novelty of this approach (and the relative inscrutability of LLMs) necessitates the adoption of rigorous methodologies that guide researchers through this process, present the range of possible approaches, and clarify limitations that are not immediately apparent, but may, in some cases, render the use of LLMs impractical. In this work, we present a comprehensive methodology for estimating word characteristics with LLMs, enriched with practical advice and lessons learned from our own experience. Our approach covers both the direct use of base LLMs and the fine-tuning of models, an alternative that can yield substantial performance gains in certain scenarios. A major emphasis in the guide is the validation of LLM-generated data with human "gold standard" norms. We also present a software framework that implements our methodology and supports both commercial and open-weight models. We illustrate the proposed approach with a case study on estimating word familiarity in English. Using base models, we achieved a Spearman correlation of 0.8 with human ratings, which increased to 0.9 when employing fine-tuned models. This methodology, framework, and set of best practices aim to serve as a reference for future research on leveraging LLMs for psycholinguistic and lexical studies.

The Generative Energy Arena (GEA): Incorporating Energy Awareness in Large Language Model (LLM) Human Evaluations

Jul 17, 2025Abstract:The evaluation of large language models is a complex task, in which several approaches have been proposed. The most common is the use of automated benchmarks in which LLMs have to answer multiple-choice questions of different topics. However, this method has certain limitations, being the most concerning, the poor correlation with the humans. An alternative approach, is to have humans evaluate the LLMs. This poses scalability issues as there is a large and growing number of models to evaluate making it impractical (and costly) to run traditional studies based on recruiting a number of evaluators and having them rank the responses of the models. An alternative approach is the use of public arenas, such as the popular LM arena, on which any user can freely evaluate models on any question and rank the responses of two models. The results are then elaborated into a model ranking. An increasingly important aspect of LLMs is their energy consumption and, therefore, evaluating how energy awareness influences the decisions of humans in selecting a model is of interest. In this paper, we present GEA, the Generative Energy Arena, an arena that incorporates information on the energy consumption of the model in the evaluation process. Preliminary results obtained with GEA are also presented, showing that for most questions, when users are aware of the energy consumption, they favor smaller and more energy efficient models. This suggests that for most user interactions, the extra cost and energy incurred by the more complex and top-performing models do not provide an increase in the perceived quality of the responses that justifies their use.

La Leaderboard: A Large Language Model Leaderboard for Spanish Varieties and Languages of Spain and Latin America

Jul 01, 2025Abstract:Leaderboards showcase the current capabilities and limitations of Large Language Models (LLMs). To motivate the development of LLMs that represent the linguistic and cultural diversity of the Spanish-speaking community, we present La Leaderboard, the first open-source leaderboard to evaluate generative LLMs in languages and language varieties of Spain and Latin America. La Leaderboard is a community-driven project that aims to establish an evaluation standard for everyone interested in developing LLMs for the Spanish-speaking community. This initial version combines 66 datasets in Basque, Catalan, Galician, and different Spanish varieties, showcasing the evaluation results of 50 models. To encourage community-driven development of leaderboards in other languages, we explain our methodology, including guidance on selecting the most suitable evaluation setup for each downstream task. In particular, we provide a rationale for using fewer few-shot examples than typically found in the literature, aiming to reduce environmental impact and facilitate access to reproducible results for a broader research community.

Understanding the Impact of Artificial Intelligence in Academic Writing: Metadata to the Rescue

Feb 23, 2025Abstract:This column advocates for including artificial intelligence (AI)-specific metadata on those academic papers that are written with the help of AI in an attempt to analyze the use of such tools for disseminating research.

Can ChatGPT Learn to Count Letters?

Feb 23, 2025Abstract:Large language models (LLMs) struggle on simple tasks such as counting the number of occurrences of a letter in a word. In this paper, we investigate if ChatGPT can learn to count letters and propose an efficient solution.

Multiple Choice Questions: Reasoning Makes Large Language Models (LLMs) More Self-Confident Even When They Are Wrong

Jan 16, 2025Abstract:One of the most widely used methods to evaluate LLMs are Multiple Choice Question (MCQ) tests. MCQ benchmarks enable the testing of LLM knowledge on almost any topic at scale as the results can be processed automatically. To help the LLM answer, a few examples called few shots can be included in the prompt. Moreover, the LLM can be asked to answer the question directly with the selected option or to first provide the reasoning and then the selected answer, which is known as chain of thought. In addition to checking whether the selected answer is correct, the evaluation can look at the LLM-estimated probability of its response as an indication of the confidence of the LLM in the response. In this paper, we study how the LLM confidence in its answer depends on whether the model has been asked to answer directly or to provide the reasoning before answering. The results of the evaluation of questions on a wide range of topics in seven different models show that LLMs are more confident in their answers when they provide reasoning before the answer. This occurs regardless of whether the selected answer is correct. Our hypothesis is that this behavior is due to the reasoning that modifies the probability of the selected answer, as the LLM predicts the answer based on the input question and the reasoning that supports the selection made. Therefore, LLM estimated probabilities seem to have intrinsic limitations that should be understood in order to use them in evaluation procedures. Interestingly, the same behavior has been observed in humans, for whom explaining an answer increases confidence in its correctness.

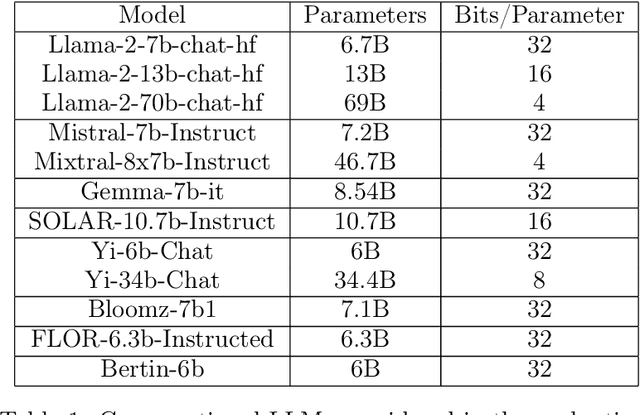

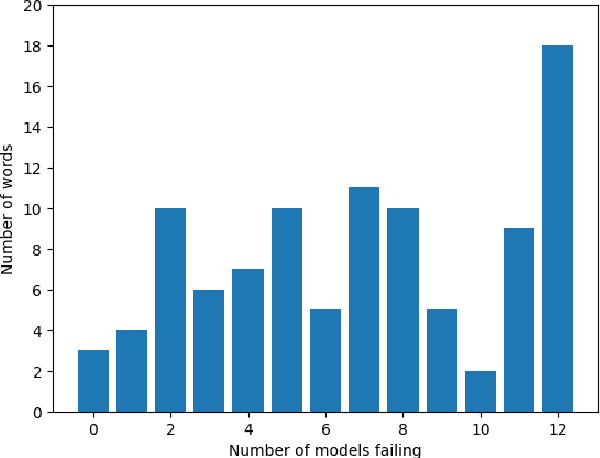

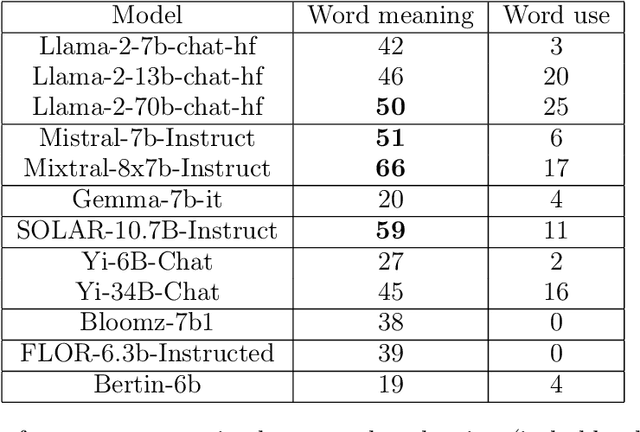

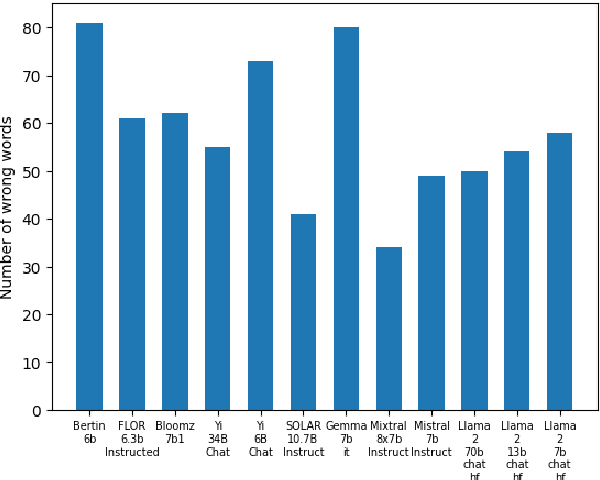

Open Source Conversational LLMs do not know most Spanish words

Mar 21, 2024

Abstract:The growing interest in Large Language Models (LLMs) and in particular in conversational models with which users can interact has led to the development of a large number of open-source chat LLMs. These models are evaluated on a wide range of benchmarks to assess their capabilities in answering questions or solving problems on almost any possible topic or to test their ability to reason or interpret texts. Instead, the evaluation of the knowledge that these models have of the languages has received much less attention. For example, the words that they can recognize and use in different languages. In this paper, we evaluate the knowledge that open-source chat LLMs have of Spanish words by testing a sample of words in a reference dictionary. The results show that open-source chat LLMs produce incorrect meanings for an important fraction of the words and are not able to use most of the words correctly to write sentences with context. These results show how Spanish is left behind in the open-source LLM race and highlight the need to push for linguistic fairness in conversational LLMs ensuring that they provide similar performance across languages.

Beware of Words: Evaluating the Lexical Richness of Conversational Large Language Models

Feb 11, 2024

Abstract:The performance of conversational Large Language Models (LLMs) in general, and of ChatGPT in particular, is currently being evaluated on many different tasks, from logical reasoning or maths to answering questions on a myriad of topics. Instead, much less attention is being devoted to the study of the linguistic features of the texts generated by these LLMs. This is surprising since LLMs are models for language, and understanding how they use the language is important. Indeed, conversational LLMs are poised to have a significant impact on the evolution of languages as they may eventually dominate the creation of new text. This means that for example, if conversational LLMs do not use a word it may become less and less frequent and eventually stop being used altogether. Therefore, evaluating the linguistic features of the text they produce and how those depend on the model parameters is the first step toward understanding the potential impact of conversational LLMs on the evolution of languages. In this paper, we consider the evaluation of the lexical richness of the text generated by LLMs and how it depends on the model parameters. A methodology is presented and used to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of lexical richness using ChatGPT as a case study. The results show how lexical richness depends on the version of ChatGPT and some of its parameters, such as the presence penalty, or on the role assigned to the model. The dataset and tools used in our analysis are released under open licenses with the goal of drawing the much-needed attention to the evaluation of the linguistic features of LLM-generated text.

The continued usefulness of vocabulary tests for evaluating large language models

Oct 23, 2023

Abstract:In their seminal article on semantic vectors, Landauer and Dumain (1997) proposed testing the quality of AI language models with a challenging vocabulary test. We show that their Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) test remains informative for contemporary major language models, since none of the models was perfect and made errors on divergent items. The TOEFL test consists of target words with four alternatives to choose from. We further tested the models on a Yes/No test that requires distinguishing between existing words and made-up nonwords. The models performed significantly worse on the nonword items, in line with other observations that current major language models provide non-existent information. The situation was worse when we generalized the tests to Spanish. Here, most models gave meanings/translations for the majority of random letter sequences. On the plus side, the best models began to perform quite well, and they also pointed to nonwords that were unknown to the test participants but can be found in dictionaries.

How many words does ChatGPT know? The answer is ChatWords

Sep 28, 2023

Abstract:The introduction of ChatGPT has put Artificial Intelligence (AI) Natural Language Processing (NLP) in the spotlight. ChatGPT adoption has been exponential with millions of users experimenting with it in a myriad of tasks and application domains with impressive results. However, ChatGPT has limitations and suffers hallucinations, for example producing answers that look plausible but they are completely wrong. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT and similar AI tools is a complex issue that is being explored from different perspectives. In this work, we contribute to those efforts with ChatWords, an automated test system, to evaluate ChatGPT knowledge of an arbitrary set of words. ChatWords is designed to be extensible, easy to use, and adaptable to evaluate also other NLP AI tools. ChatWords is publicly available and its main goal is to facilitate research on the lexical knowledge of AI tools. The benefits of ChatWords are illustrated with two case studies: evaluating the knowledge that ChatGPT has of the Spanish lexicon (taken from the official dictionary of the "Real Academia Espa\~nola") and of the words that appear in the Quixote, the well-known novel written by Miguel de Cervantes. The results show that ChatGPT is only able to recognize approximately 80% of the words in the dictionary and 90% of the words in the Quixote, in some cases with an incorrect meaning. The implications of the lexical knowledge of NLP AI tools and potential applications of ChatWords are also discussed providing directions for further work on the study of the lexical knowledge of AI tools.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge