Benjamin A. Christie

Language Movement Primitives: Grounding Language Models in Robot Motion

Feb 02, 2026Abstract:Enabling robots to perform novel manipulation tasks from natural language instructions remains a fundamental challenge in robotics, despite significant progress in generalized problem solving with foundational models. Large vision and language models (VLMs) are capable of processing high-dimensional input data for visual scene and language understanding, as well as decomposing tasks into a sequence of logical steps; however, they struggle to ground those steps in embodied robot motion. On the other hand, robotics foundation models output action commands, but require in-domain fine-tuning or experience before they are able to perform novel tasks successfully. At its core, there still remains the fundamental challenge of connecting abstract task reasoning with low-level motion control. To address this disconnect, we propose Language Movement Primitives (LMPs), a framework that grounds VLM reasoning in Dynamic Movement Primitive (DMP) parameterization. Our key insight is that DMPs provide a small number of interpretable parameters, and VLMs can set these parameters to specify diverse, continuous, and stable trajectories. Put another way: VLMs can reason over free-form natural language task descriptions, and semantically ground their desired motions into DMPs -- bridging the gap between high-level task reasoning and low-level position and velocity control. Building on this combination of VLMs and DMPs, we formulate our LMP pipeline for zero-shot robot manipulation that effectively completes tabletop manipulation problems by generating a sequence of DMP motions. Across 20 real-world manipulation tasks, we show that LMP achieves 80% task success as compared to 31% for the best-performing baseline. See videos at our website: https://collab.me.vt.edu/lmp

A Modular Haptic Display with Reconfigurable Signals for Personalized Information Transfer

Jun 06, 2025Abstract:We present a customizable soft haptic system that integrates modular hardware with an information-theoretic algorithm to personalize feedback for different users and tasks. Our platform features modular, multi-degree-of-freedom pneumatic displays, where different signal types, such as pressure, frequency, and contact area, can be activated or combined using fluidic logic circuits. These circuits simplify control by reducing reliance on specialized electronics and enabling coordinated actuation of multiple haptic elements through a compact set of inputs. Our approach allows rapid reconfiguration of haptic signal rendering through hardware-level logic switching without rewriting code. Personalization of the haptic interface is achieved through the combination of modular hardware and software-driven signal selection. To determine which display configurations will be most effective, we model haptic communication as a signal transmission problem, where an agent must convey latent information to the user. We formulate the optimization problem to identify the haptic hardware setup that maximizes the information transfer between the intended message and the user's interpretation, accounting for individual differences in sensitivity, preferences, and perceptual salience. We evaluate this framework through user studies where participants interact with reconfigurable displays under different signal combinations. Our findings support the role of modularity and personalization in creating multimodal haptic interfaces and advance the development of reconfigurable systems that adapt with users in dynamic human-machine interaction contexts.

Safe Interaction via Monte Carlo Linear-Quadratic Games

Apr 08, 2025Abstract:Safety is critical during human-robot interaction. But -- because people are inherently unpredictable -- it is often difficult for robots to plan safe behaviors. Instead of relying on our ability to anticipate humans, here we identify robot policies that are robust to unexpected human decisions. We achieve this by formulating human-robot interaction as a zero-sum game, where (in the worst case) the human's actions directly conflict with the robot's objective. Solving for the Nash Equilibrium of this game provides robot policies that maximize safety and performance across a wide range of human actions. Existing approaches attempt to find these optimal policies by leveraging Hamilton-Jacobi analysis (which is intractable) or linear-quadratic approximations (which are inexact). By contrast, in this work we propose a computationally efficient and theoretically justified method that converges towards the Nash Equilibrium policy. Our approach (which we call MCLQ) leverages linear-quadratic games to obtain an initial guess at safe robot behavior, and then iteratively refines that guess with a Monte Carlo search. Not only does MCLQ provide real-time safety adjustments, but it also enables the designer to tune how conservative the robot is -- preventing the system from focusing on unrealistic human behaviors. Our simulations and user study suggest that this approach advances safety in terms of both computation time and expected performance. See videos of our experiments here: https://youtu.be/KJuHeiWVuWY.

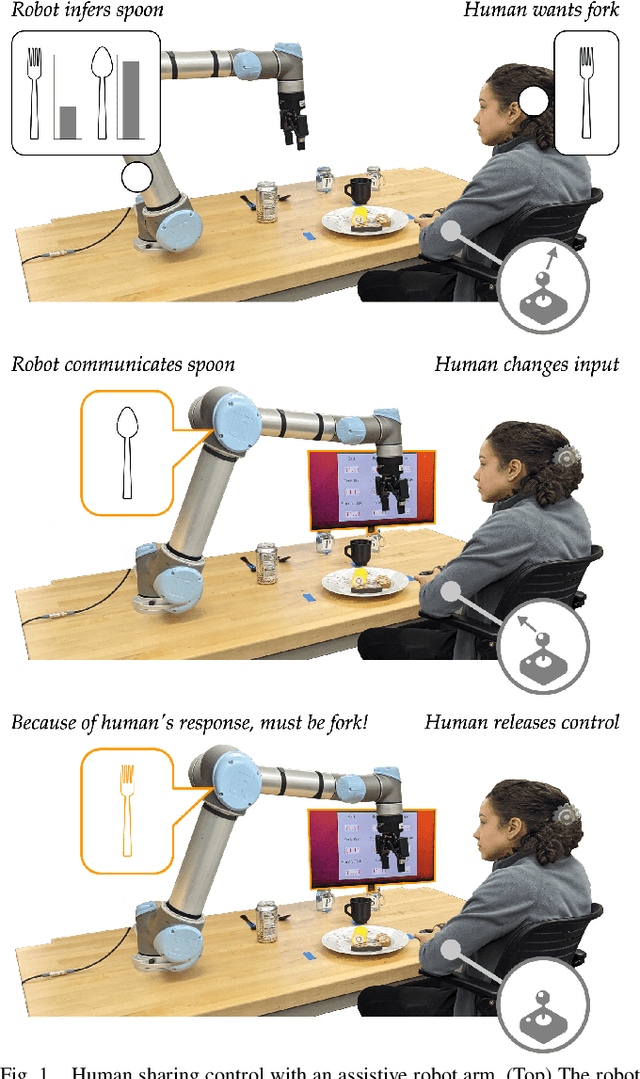

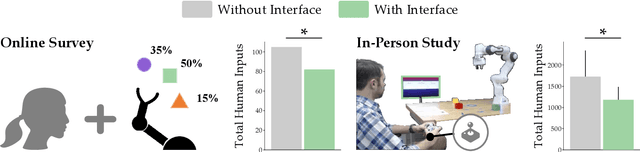

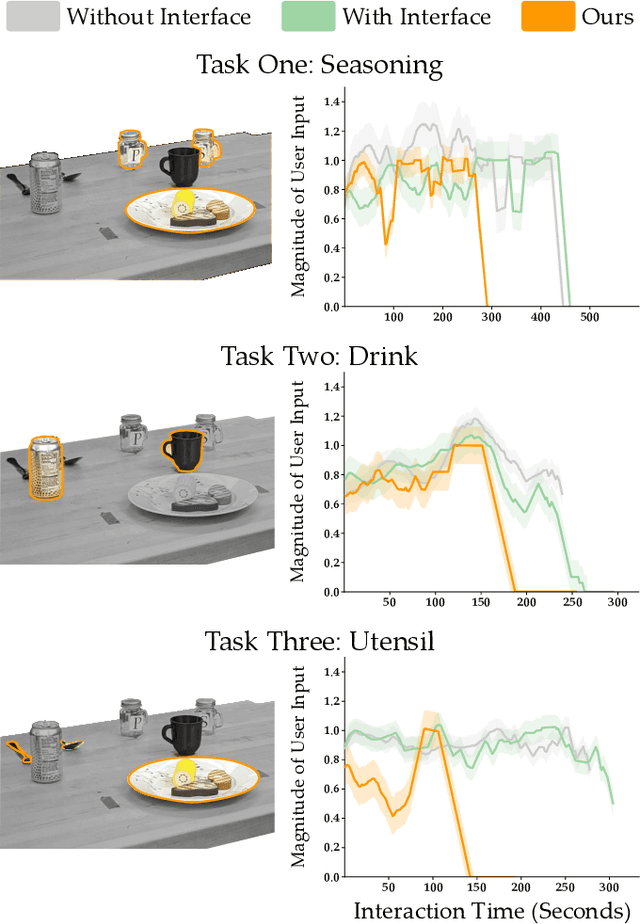

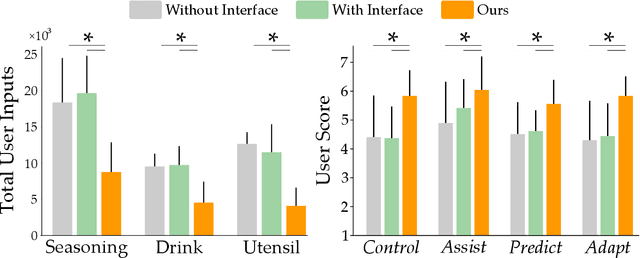

Aligning Learning with Communication in Shared Autonomy

Mar 18, 2024

Abstract:Assistive robot arms can help humans by partially automating their desired tasks. Consider an adult with motor impairments controlling an assistive robot arm to eat dinner. The robot can reduce the number of human inputs -- and how precise those inputs need to be -- by recognizing what the human wants (e.g., a fork) and assisting for that task (e.g., moving towards the fork). Prior research has largely focused on learning the human's task and providing meaningful assistance. But as the robot learns and assists, we also need to ensure that the human understands the robot's intent (e.g., does the human know the robot is reaching for a fork?). In this paper, we study the effects of communicating learned assistance from the robot back to the human operator. We do not focus on the specific interfaces used for communication. Instead, we develop experimental and theoretical models of a) how communication changes the way humans interact with assistive robot arms, and b) how robots can harness these changes to better align with the human's intent. We first conduct online and in-person user studies where participants operate robots that provide partial assistance, and we measure how the human's inputs change with and without communication. With communication, we find that humans are more likely to intervene when the robot incorrectly predicts their intent, and more likely to release control when the robot correctly understands their task. We then use these findings to modify an established robot learning algorithm so that the robot can correctly interpret the human's inputs when communication is present. Our results from a second in-person user study suggest that this combination of communication and learning outperforms assistive systems that isolate either learning or communication.

Accelerating Interface Adaptation with User-Friendly Priors

Mar 11, 2024

Abstract:Robots often need to convey information to human users. For example, robots can leverage visual, auditory, and haptic interfaces to display their intent or express their internal state. In some scenarios there are socially agreed upon conventions for what these signals mean: e.g., a red light indicates an autonomous car is slowing down. But as robots develop new capabilities and seek to convey more complex data, the meaning behind their signals is not always mutually understood: one user might think a flashing light indicates the autonomous car is an aggressive driver, while another user might think the same signal means the autonomous car is defensive. In this paper we enable robots to adapt their interfaces to the current user so that the human's personalized interpretation is aligned with the robot's meaning. We start with an information theoretic end-to-end approach, which automatically tunes the interface policy to optimize the correlation between human and robot. But to ensure that this learning policy is intuitive -- and to accelerate how quickly the interface adapts to the human -- we recognize that humans have priors over how interfaces should function. For instance, humans expect interface signals to be proportional and convex. Our approach biases the robot's interface towards these priors, resulting in signals that are adapted to the current user while still following social expectations. Our simulations and user study results across $15$ participants suggest that these priors improve robot-to-human communication. See videos here: https://youtu.be/Re3OLg57hp8

LIMIT: Learning Interfaces to Maximize Information Transfer

Apr 17, 2023Abstract:Robots can use auditory, visual, or haptic interfaces to convey information to human users. The way these interfaces select signals is typically pre-defined by the designer: for instance, a haptic wristband might vibrate when the robot is moving and squeeze when the robot stops. But different people interpret the same signals in different ways, so that what makes sense to one person might be confusing or unintuitive to another. In this paper we introduce a unified algorithmic formalism for learning co-adaptive interfaces from scratch. Our method does not need to know the human's task (i.e., what the human is using these signals for). Instead, our insight is that interpretable interfaces should select signals that maximize correlation between the human's actions and the information the interface is trying to convey. Applying this insight we develop LIMIT: Learning Interfaces to Maximize Information Transfer. LIMIT optimizes a tractable, real-time proxy of information gain in continuous spaces. The first time a person works with our system the signals may appear random; but over repeated interactions the interface learns a one-to-one mapping between displayed signals and human responses. Our resulting approach is both personalized to the current user and not tied to any specific interface modality. We compare LIMIT to state-of-the-art baselines across controlled simulations, an online survey, and an in-person user study with auditory, visual, and haptic interfaces. Overall, our results suggest that LIMIT learns interfaces that enable users to complete the task more quickly and efficiently, and users subjectively prefer LIMIT to the alternatives. See videos here: https://youtu.be/IvQ3TM1_2fA.

Towards Robots that Influence Humans over Long-Term Interaction

Sep 21, 2022

Abstract:When humans interact with robots influence is inevitable. Consider an autonomous car driving near a human: the speed and steering of the autonomous car will affect how the human drives. Prior works have developed frameworks that enable robots to influence humans towards desired behaviors. But while these approaches are effective in the short-term (i.e., the first few human-robot interactions), here we explore long-term influence (i.e., repeated interactions between the same human and robot). Our central insight is that humans are dynamic: people adapt to robots, and behaviors which are influential now may fall short once the human learns to anticipate the robot's actions. With this insight, we experimentally demonstrate that a prevalent game-theoretic formalism for generating influential robot behaviors becomes less effective over repeated interactions. Next, we propose three modifications to Stackelberg games that make the robot's policy both influential and unpredictable. We finally test these modifications across simulations and user studies: our results suggest that robots which purposely make their actions harder to anticipate are better able to maintain influence over long-term interaction. See videos here: https://youtu.be/ydO83cgjZ2Q

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge