Alexandra M. Proca

Flexible task abstractions emerge in linear networks with fast and bounded units

Nov 06, 2024

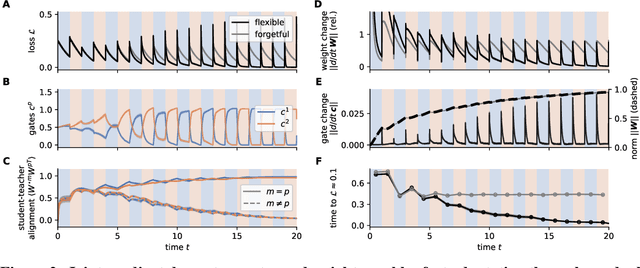

Abstract:Animals survive in dynamic environments changing at arbitrary timescales, but such data distribution shifts are a challenge to neural networks. To adapt to change, neural systems may change a large number of parameters, which is a slow process involving forgetting past information. In contrast, animals leverage distribution changes to segment their stream of experience into tasks and associate them with internal task abstracts. Animals can then respond flexibly by selecting the appropriate task abstraction. However, how such flexible task abstractions may arise in neural systems remains unknown. Here, we analyze a linear gated network where the weights and gates are jointly optimized via gradient descent, but with neuron-like constraints on the gates including a faster timescale, nonnegativity, and bounded activity. We observe that the weights self-organize into modules specialized for tasks or sub-tasks encountered, while the gates layer forms unique representations that switch the appropriate weight modules (task abstractions). We analytically reduce the learning dynamics to an effective eigenspace, revealing a virtuous cycle: fast adapting gates drive weight specialization by protecting previous knowledge, while weight specialization in turn increases the update rate of the gating layer. Task switching in the gating layer accelerates as a function of curriculum block size and task training, mirroring key findings in cognitive neuroscience. We show that the discovered task abstractions support generalization through both task and subtask composition, and we extend our findings to a non-linear network switching between two tasks. Overall, our work offers a theory of cognitive flexibility in animals as arising from joint gradient descent on synaptic and neural gating in a neural network architecture.

From Lazy to Rich: Exact Learning Dynamics in Deep Linear Networks

Sep 22, 2024

Abstract:Biological and artificial neural networks develop internal representations that enable them to perform complex tasks. In artificial networks, the effectiveness of these models relies on their ability to build task specific representation, a process influenced by interactions among datasets, architectures, initialization strategies, and optimization algorithms. Prior studies highlight that different initializations can place networks in either a lazy regime, where representations remain static, or a rich/feature learning regime, where representations evolve dynamically. Here, we examine how initialization influences learning dynamics in deep linear neural networks, deriving exact solutions for lambda-balanced initializations-defined by the relative scale of weights across layers. These solutions capture the evolution of representations and the Neural Tangent Kernel across the spectrum from the rich to the lazy regimes. Our findings deepen the theoretical understanding of the impact of weight initialization on learning regimes, with implications for continual learning, reversal learning, and transfer learning, relevant to both neuroscience and practical applications.

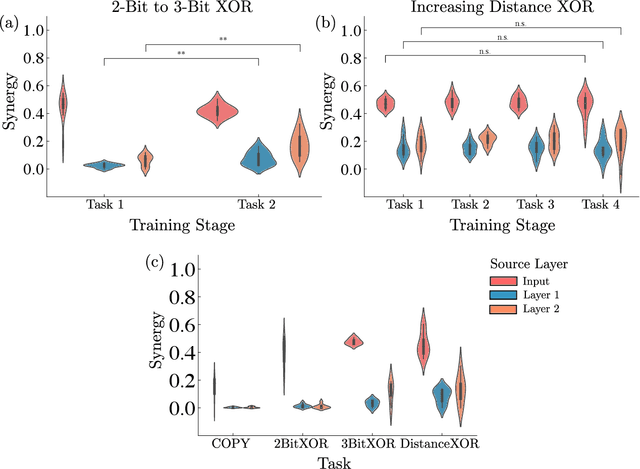

Synergistic information supports modality integration and flexible learning in neural networks solving multiple tasks

Oct 06, 2022

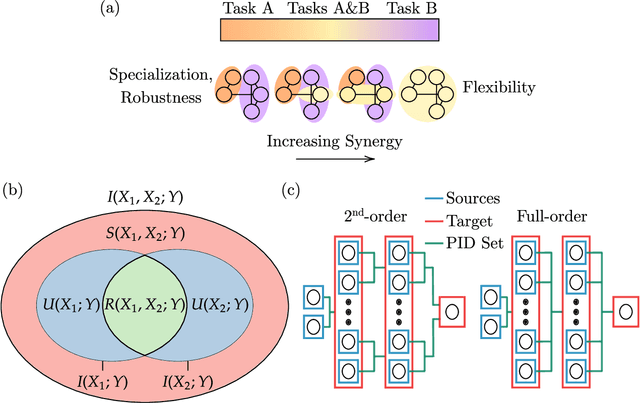

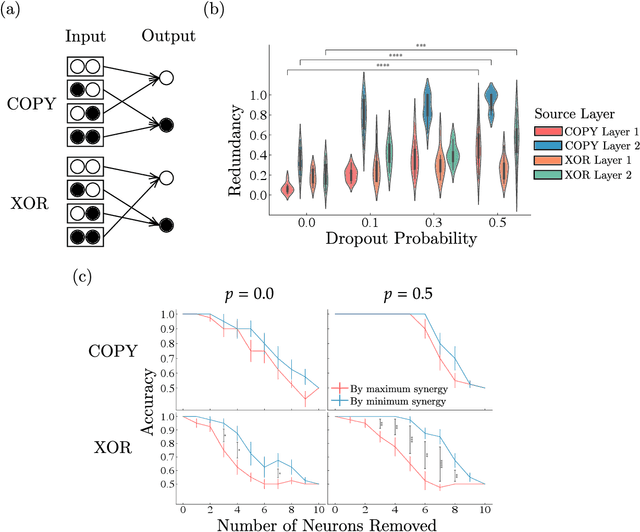

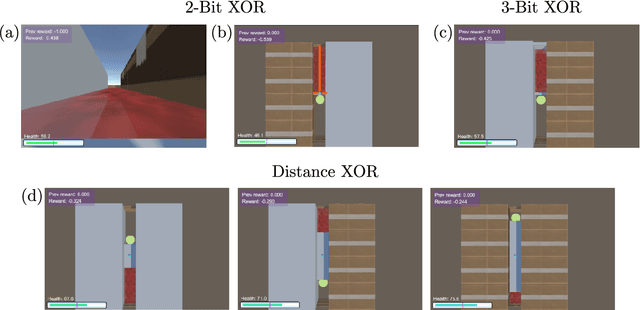

Abstract:Striking progress has recently been made in understanding human cognition by analyzing how its neuronal underpinnings are engaged in different modes of information processing. Specifically, neural information can be decomposed into synergistic, redundant, and unique features, with synergistic components being particularly aligned with complex cognition. However, two fundamental questions remain unanswered: (a) precisely how and why a cognitive system can become highly synergistic; and (b) how these informational states map onto artificial neural networks in various learning modes. To address these questions, here we employ an information-decomposition framework to investigate the information processing strategies adopted by simple artificial neural networks performing a variety of cognitive tasks in both supervised and reinforcement learning settings. Our results show that synergy increases as neural networks learn multiple diverse tasks. Furthermore, performance in tasks requiring integration of multiple information sources critically relies on synergistic neurons. Finally, randomly turning off neurons during training through dropout increases network redundancy, corresponding to an increase in robustness. Overall, our results suggest that while redundant information is required for robustness to perturbations in the learning process, synergistic information is used to combine information from multiple modalities -- and more generally for flexible and efficient learning. These findings open the door to new ways of investigating how and why learning systems employ specific information-processing strategies, and support the principle that the capacity for general-purpose learning critically relies in the system's information dynamics.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge