Walter Sinnott-Armstrong

Moral Change or Noise? On Problems of Aligning AI With Temporally Unstable Human Feedback

Nov 13, 2025Abstract:Alignment methods in moral domains seek to elicit moral preferences of human stakeholders and incorporate them into AI. This presupposes moral preferences as static targets, but such preferences often evolve over time. Proper alignment of AI to dynamic human preferences should ideally account for "legitimate" changes to moral reasoning, while ignoring changes related to attention deficits, cognitive biases, or other arbitrary factors. However, common AI alignment approaches largely neglect temporal changes in preferences, posing serious challenges to proper alignment, especially in high-stakes applications of AI, e.g., in healthcare domains, where misalignment can jeopardize the trustworthiness of the system and yield serious individual and societal harms. This work investigates the extent to which people's moral preferences change over time, and the impact of such changes on AI alignment. Our study is grounded in the kidney allocation domain, where we elicit responses to pairwise comparisons of hypothetical kidney transplant patients from over 400 participants across 3-5 sessions. We find that, on average, participants change their response to the same scenario presented at different times around 6-20% of the time (exhibiting "response instability"). Additionally, we observe significant shifts in several participants' retrofitted decision-making models over time (capturing "model instability"). The predictive performance of simple AI models decreases as a function of both response and model instability. Moreover, predictive performance diminishes over time, highlighting the importance of accounting for temporal changes in preferences during training. These findings raise fundamental normative and technical challenges relevant to AI alignment, highlighting the need to better understand the object of alignment (what to align to) when user preferences change significantly over time.

Towards Cognitively-Faithful Decision-Making Models to Improve AI Alignment

Sep 04, 2025Abstract:Recent AI work trends towards incorporating human-centric objectives, with the explicit goal of aligning AI models to personal preferences and societal values. Using standard preference elicitation methods, researchers and practitioners build models of human decisions and judgments, which are then used to align AI behavior with that of humans. However, models commonly used in such elicitation processes often do not capture the true cognitive processes of human decision making, such as when people use heuristics to simplify information associated with a decision problem. As a result, models learned from people's decisions often do not align with their cognitive processes, and can not be used to validate the learning framework for generalization to other decision-making tasks. To address this limitation, we take an axiomatic approach to learning cognitively faithful decision processes from pairwise comparisons. Building on the vast literature characterizing the cognitive processes that contribute to human decision-making, and recent work characterizing such processes in pairwise comparison tasks, we define a class of models in which individual features are first processed and compared across alternatives, and then the processed features are then aggregated via a fixed rule, such as the Bradley-Terry rule. This structured processing of information ensures such models are realistic and feasible candidates to represent underlying human decision-making processes. We demonstrate the efficacy of this modeling approach in learning interpretable models of human decision making in a kidney allocation task, and show that our proposed models match or surpass the accuracy of prior models of human pairwise decision-making.

Can AI Model the Complexities of Human Moral Decision-Making? A Qualitative Study of Kidney Allocation Decisions

Mar 02, 2025Abstract:A growing body of work in Ethical AI attempts to capture human moral judgments through simple computational models. The key question we address in this work is whether such simple AI models capture {the critical} nuances of moral decision-making by focusing on the use case of kidney allocation. We conducted twenty interviews where participants explained their rationale for their judgments about who should receive a kidney. We observe participants: (a) value patients' morally-relevant attributes to different degrees; (b) use diverse decision-making processes, citing heuristics to reduce decision complexity; (c) can change their opinions; (d) sometimes lack confidence in their decisions (e.g., due to incomplete information); and (e) express enthusiasm and concern regarding AI assisting humans in kidney allocation decisions. Based on these findings, we discuss challenges of computationally modeling moral judgments {as a stand-in for human input}, highlight drawbacks of current approaches, and suggest future directions to address these issues.

Relational Norms for Human-AI Cooperation

Feb 17, 2025Abstract:How we should design and interact with social artificial intelligence depends on the socio-relational role the AI is meant to emulate or occupy. In human society, relationships such as teacher-student, parent-child, neighbors, siblings, or employer-employee are governed by specific norms that prescribe or proscribe cooperative functions including hierarchy, care, transaction, and mating. These norms shape our judgments of what is appropriate for each partner. For example, workplace norms may allow a boss to give orders to an employee, but not vice versa, reflecting hierarchical and transactional expectations. As AI agents and chatbots powered by large language models are increasingly designed to serve roles analogous to human positions - such as assistant, mental health provider, tutor, or romantic partner - it is imperative to examine whether and how human relational norms should extend to human-AI interactions. Our analysis explores how differences between AI systems and humans, such as the absence of conscious experience and immunity to fatigue, may affect an AI's capacity to fulfill relationship-specific functions and adhere to corresponding norms. This analysis, which is a collaborative effort by philosophers, psychologists, relationship scientists, ethicists, legal experts, and AI researchers, carries important implications for AI systems design, user behavior, and regulation. While we accept that AI systems can offer significant benefits such as increased availability and consistency in certain socio-relational roles, they also risk fostering unhealthy dependencies or unrealistic expectations that could spill over into human-human relationships. We propose that understanding and thoughtfully shaping (or implementing) suitable human-AI relational norms will be crucial for ensuring that human-AI interactions are ethical, trustworthy, and favorable to human well-being.

On The Stability of Moral Preferences: A Problem with Computational Elicitation Methods

Aug 05, 2024

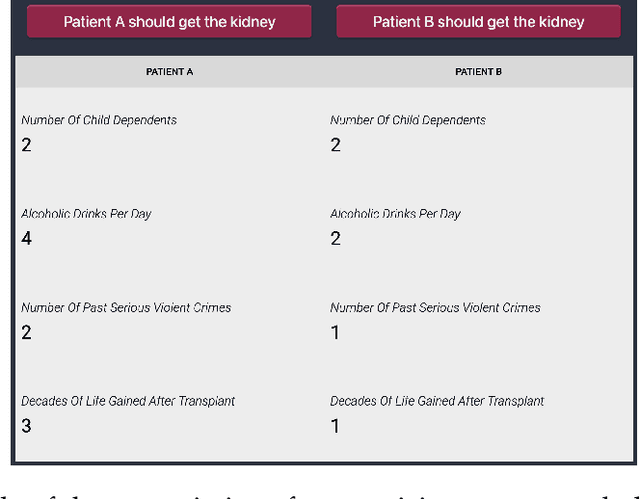

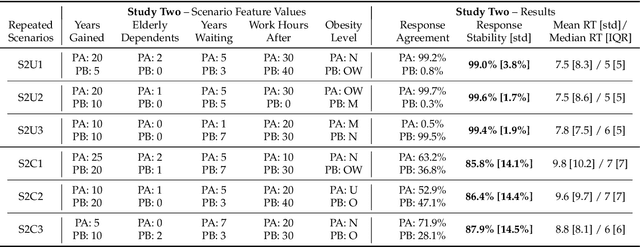

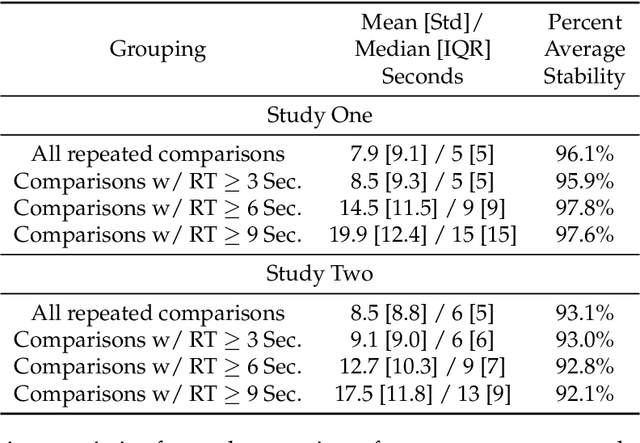

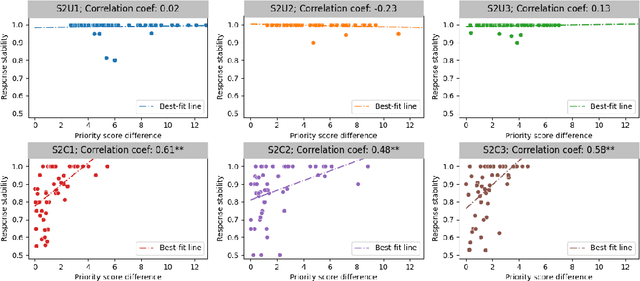

Abstract:Preference elicitation frameworks feature heavily in the research on participatory ethical AI tools and provide a viable mechanism to enquire and incorporate the moral values of various stakeholders. As part of the elicitation process, surveys about moral preferences, opinions, and judgments are typically administered only once to each participant. This methodological practice is reasonable if participants' responses are stable over time such that, all other relevant factors being held constant, their responses today will be the same as their responses to the same questions at a later time. However, we do not know how often that is the case. It is possible that participants' true moral preferences change, are subject to temporary moods or whims, or are influenced by environmental factors we don't track. If participants' moral responses are unstable in such ways, it would raise important methodological and theoretical issues for how participants' true moral preferences, opinions, and judgments can be ascertained. We address this possibility here by asking the same survey participants the same moral questions about which patient should receive a kidney when only one is available ten times in ten different sessions over two weeks, varying only presentation order across sessions. We measured how often participants gave different responses to simple (Study One) and more complicated (Study Two) repeated scenarios. On average, the fraction of times participants changed their responses to controversial scenarios was around 10-18% across studies, and this instability is observed to have positive associations with response time and decision-making difficulty. We discuss the implications of these results for the efficacy of moral preference elicitation, highlighting the role of response instability in causing value misalignment between stakeholders and AI tools trained on their moral judgments.

On the Pros and Cons of Active Learning for Moral Preference Elicitation

Jul 26, 2024Abstract:Computational preference elicitation methods are tools used to learn people's preferences quantitatively in a given context. Recent works on preference elicitation advocate for active learning as an efficient method to iteratively construct queries (framed as comparisons between context-specific cases) that are likely to be most informative about an agent's underlying preferences. In this work, we argue that the use of active learning for moral preference elicitation relies on certain assumptions about the underlying moral preferences, which can be violated in practice. Specifically, we highlight the following common assumptions (a) preferences are stable over time and not sensitive to the sequence of presented queries, (b) the appropriate hypothesis class is chosen to model moral preferences, and (c) noise in the agent's responses is limited. While these assumptions can be appropriate for preference elicitation in certain domains, prior research on moral psychology suggests they may not be valid for moral judgments. Through a synthetic simulation of preferences that violate the above assumptions, we observe that active learning can have similar or worse performance than a basic random query selection method in certain settings. Yet, simulation results also demonstrate that active learning can still be viable if the degree of instability or noise is relatively small and when the agent's preferences can be approximately represented with the hypothesis class used for learning. Our study highlights the nuances associated with effective moral preference elicitation in practice and advocates for the cautious use of active learning as a methodology to learn moral preferences.

Towards Stable Preferences for Stakeholder-aligned Machine Learning

Feb 02, 2024

Abstract:In response to the pressing challenge of kidney allocation, characterized by growing demands for organs, this research sets out to develop a data-driven solution to this problem, which also incorporates stakeholder values. The primary objective of this study is to create a method for learning both individual and group-level preferences pertaining to kidney allocations. Drawing upon data from the 'Pairwise Kidney Patient Online Survey.' Leveraging two distinct datasets and evaluating across three levels - Individual, Group and Stability - we employ machine learning classifiers assessed through several metrics. The Individual level model predicts individual participant preferences, the Group level model aggregates preferences across participants, and the Stability level model, an extension of the Group level, evaluates the stability of these preferences over time. By incorporating stakeholder preferences into the kidney allocation process, we aspire to advance the ethical dimensions of organ transplantation, contributing to more transparent and equitable practices while promoting the integration of moral values into algorithmic decision-making.

Indecision Modeling

Dec 15, 2020

Abstract:AI systems are often used to make or contribute to important decisions in a growing range of applications, including criminal justice, hiring, and medicine. Since these decisions impact human lives, it is important that the AI systems act in ways which align with human values. Techniques for preference modeling and social choice help researchers learn and aggregate peoples' preferences, which are used to guide AI behavior; thus, it is imperative that these learned preferences are accurate. These techniques often assume that people are willing to express strict preferences over alternatives; which is not true in practice. People are often indecisive, and especially so when their decision has moral implications. The philosophy and psychology literature shows that indecision is a measurable and nuanced behavior -- and that there are several different reasons people are indecisive. This complicates the task of both learning and aggregating preferences, since most of the relevant literature makes restrictive assumptions on the meaning of indecision. We begin to close this gap by formalizing several mathematical \emph{indecision} models based on theories from philosophy, psychology, and economics; these models can be used to describe (indecisive) agent decisions, both when they are allowed to express indecision and when they are not. We test these models using data collected from an online survey where participants choose how to (hypothetically) allocate organs to patients waiting for a transplant.

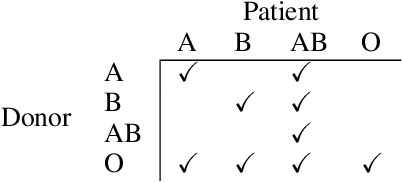

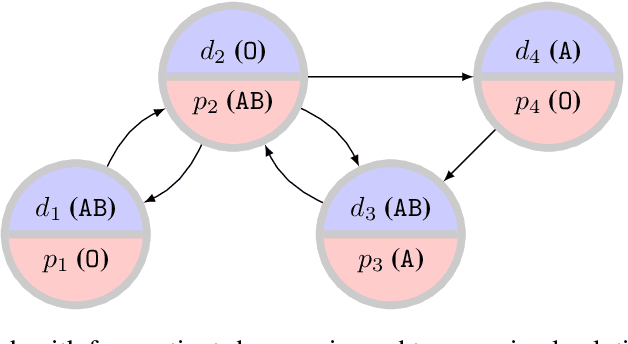

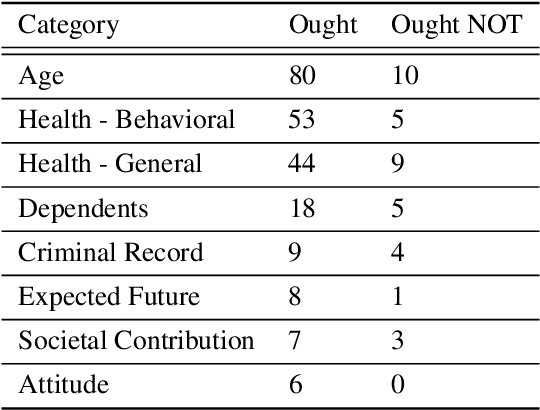

Adapting a Kidney Exchange Algorithm to Align with Human Values

May 19, 2020

Abstract:The efficient and fair allocation of limited resources is a classical problem in economics and computer science. In kidney exchanges, a central market maker allocates living kidney donors to patients in need of an organ. Patients and donors in kidney exchanges are prioritized using ad-hoc weights decided on by committee and then fed into an allocation algorithm that determines who gets what--and who does not. In this paper, we provide an end-to-end methodology for estimating weights of individual participant profiles in a kidney exchange. We first elicit from human subjects a list of patient attributes they consider acceptable for the purpose of prioritizing patients (e.g., medical characteristics, lifestyle choices, and so on). Then, we ask subjects comparison queries between patient profiles and estimate weights in a principled way from their responses. We show how to use these weights in kidney exchange market clearing algorithms. We then evaluate the impact of the weights in simulations and find that the precise numerical values of the weights we computed matter little, other than the ordering of profiles that they imply. However, compared to not prioritizing patients at all, there is a significant effect, with certain classes of patients being (de)prioritized based on the human-elicited value judgments.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge