Matthieu Doutreligne

SODA

Causal thinking for decision making on Electronic Health Records: why and how

Aug 03, 2023

Abstract:Accurate predictions, as with machine learning, may not suffice to provide optimal healthcare for every patient. Indeed, prediction can be driven by shortcuts in the data, such as racial biases. Causal thinking is needed for data-driven decisions. Here, we give an introduction to the key elements, focusing on routinely-collected data, electronic health records (EHRs) and claims data. Using such data to assess the value of an intervention requires care: temporal dependencies and existing practices easily confound the causal effect. We present a step-by-step framework to help build valid decision making from real-life patient records by emulating a randomized trial before individualizing decisions, eg with machine learning. Our framework highlights the most important pitfalls and considerations in analysing EHRs or claims data to draw causal conclusions. We illustrate the various choices in studying the effect of albumin on sepsis mortality in the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care database (MIMIC-IV). We study the impact of various choices at every step, from feature extraction to causal-estimator selection. In a tutorial spirit, the code and the data are openly available.

Hybrid Approaches for our Participation to the n2c2 Challenge on Cohort Selection for Clinical Trials

Mar 19, 2019

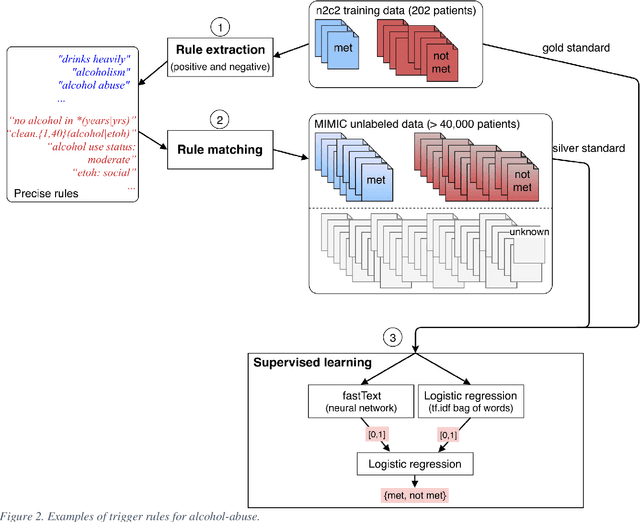

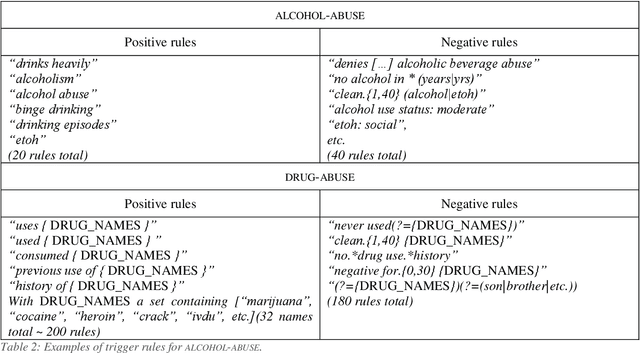

Abstract:Objective: Natural language processing can help minimize human intervention in identifying patients meeting eligibility criteria for clinical trials, but there is still a long way to go to obtain a general and systematic approach that is useful for researchers. We describe two methods taking a step in this direction and present their results obtained during the n2c2 challenge on cohort selection for clinical trials. Materials and Methods: The first method is a weakly supervised method using an unlabeled corpus (MIMIC) to build a silver standard, by producing semi-automatically a small and very precise set of rules to detect some samples of positive and negative patients. This silver standard is then used to train a traditional supervised model. The second method is a terminology-based approach where a medical expert selects the appropriate concepts, and a procedure is defined to search the terms and check the structural or temporal constraints. Results: On the n2c2 dataset containing annotated data about 13 selection criteria on 288 patients, we obtained an overall F1-measure of 0.8969, which is the third best result out of 45 participant teams, with no statistically significant difference with the best-ranked team. Discussion: Both approaches obtained very encouraging results and apply to different types of criteria. The weakly supervised method requires explicit descriptions of positive and negative examples in some reports. The terminology-based method is very efficient when medical concepts carry most of the relevant information. Conclusion: It is unlikely that much more annotated data will be soon available for the task of identifying a wide range of patient phenotypes. One must focus on weakly or non-supervised learning methods using both structured and unstructured data and relying on a comprehensive representation of the patients.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge