Matthew Q. Hill

The University of Texas at Dallas

The Early Bird Identifies the Worm: You Can't Beat a Head Start in Long-Term Body Re-ID (ECHO-BID)

Jul 23, 2025Abstract:Person identification in unconstrained viewing environments presents significant challenges due to variations in distance, viewpoint, imaging conditions, and clothing. We introduce $\textbf{E}$va $\textbf{C}$lothes-Change from $\textbf{H}$idden $\textbf{O}$bjects - $\textbf{B}$ody $\textbf{ID}$entification (ECHO-BID), a class of long-term re-id models built on object-pretrained EVA-02 Large backbones. We compare ECHO-BID to 9 other models that vary systematically in backbone architecture, model size, scale of object classification pretraining, and transfer learning protocol. Models were evaluated on benchmark datasets across constrained, unconstrained, and occluded settings. ECHO-BID, with transfer learning on the most challenging clothes-change data, achieved state-of-the-art results on long-term re-id -- substantially outperforming other methods. ECHO-BID also surpassed other methods by a wide margin in occluded viewing scenarios. A combination of increased model size and Masked Image Modeling during pretraining underlie ECHO-BID's strong performance on long-term re-id. Notably, a smaller, but more challenging transfer learning dataset, generalized better across datasets than a larger, less challenging one. However, the larger dataset with an additional fine-tuning step proved best on the most difficult data. Selecting the correct pretrained backbone architecture and transfer learning protocols can drive substantial gains in long-term re-id performance.

Recognizing People by Body Shape Using Deep Networks of Images and Words

May 30, 2023

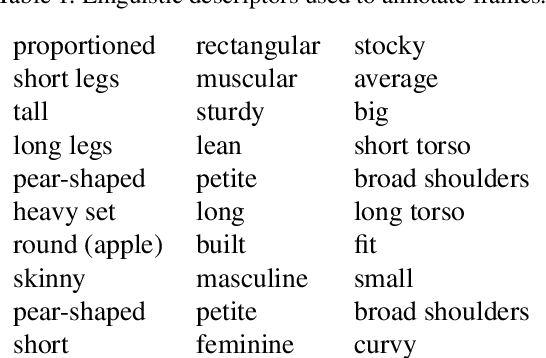

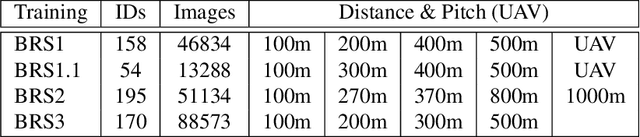

Abstract:Common and important applications of person identification occur at distances and viewpoints in which the face is not visible or is not sufficiently resolved to be useful. We examine body shape as a biometric across distance and viewpoint variation. We propose an approach that combines standard object classification networks with representations based on linguistic (word-based) descriptions of bodies. Algorithms with and without linguistic training were compared on their ability to identify people from body shape in images captured across a large range of distances/views (close-range, 100m, 200m, 270m, 300m, 370m, 400m, 490m, 500m, 600m, and at elevated pitch in images taken by an unmanned aerial vehicle [UAV]). Accuracy, as measured by identity-match ranking and false accept errors in an open-set test, was surprisingly good. For identity-ranking, linguistic models were more accurate for close-range images, whereas non-linguistic models fared better at intermediary distances. Fusion of the linguistic and non-linguistic embeddings improved performance at all, but the farthest distance. Although the non-linguistic model yielded fewer false accepts at all distances, fusion of the linguistic and non-linguistic models decreased false accepts for all, but the UAV images. We conclude that linguistic and non-linguistic representations of body shape can offer complementary identity information for bodies that can improve identification in applications of interest.

Single Unit Status in Deep Convolutional Neural Network Codes for Face Identification: Sparseness Redefined

Mar 01, 2020

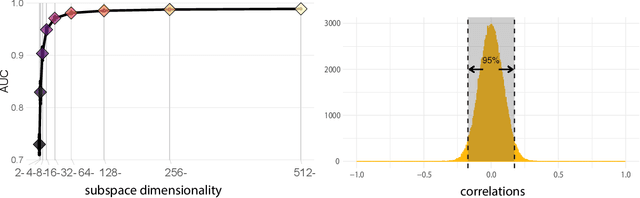

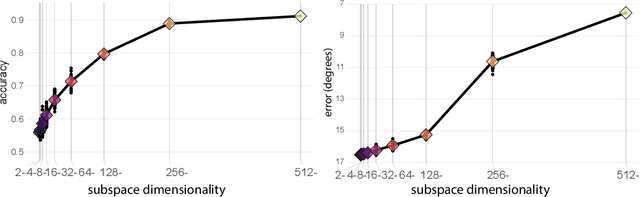

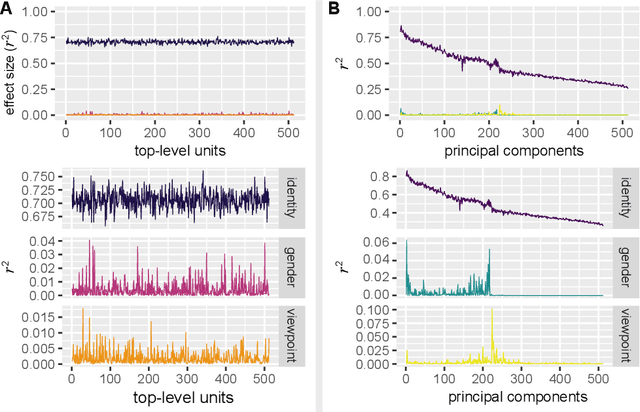

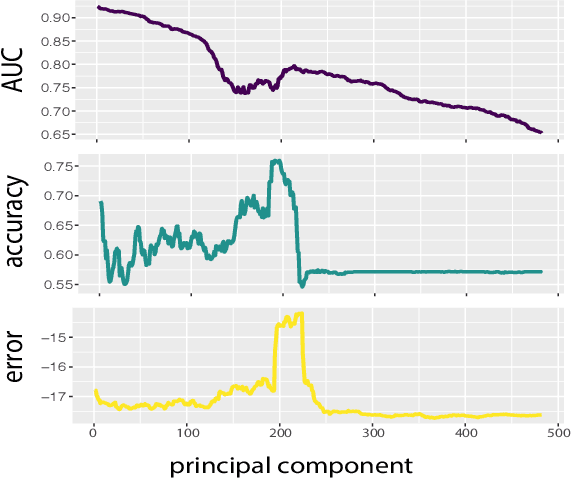

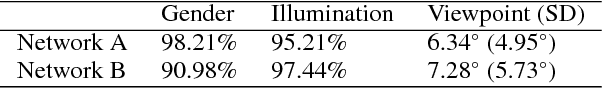

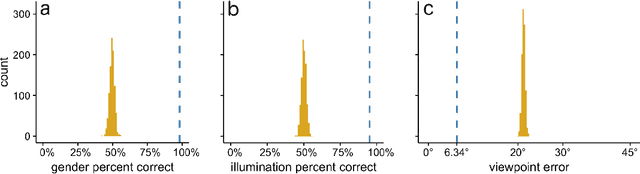

Abstract:Deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) trained for face identification develop representations that generalize over variable images, while retaining subject (e.g., gender) and image (e.g., viewpoint) information. Identity, gender, and viewpoint codes were studied at the "neural unit" and ensemble levels of a face-identification network. At the unit level, identification, gender classification, and viewpoint estimation were measured by deleting units to create variably-sized, randomly-sampled subspaces at the top network layer. Identification of 3,531 identities remained high (area under the ROC approximately 1.0) as dimensionality decreased from 512 units to 16 (0.95), 4 (0.80), and 2 (0.72) units. Individual identities separated statistically on every top-layer unit. Cross-unit responses were minimally correlated, indicating that units code non-redundant identity cues. This "distributed" code requires only a sparse, random sample of units to identify faces accurately. Gender classification declined gradually and viewpoint estimation fell steeply as dimensionality decreased. Individual units were weakly predictive of gender and viewpoint, but ensembles proved effective predictors. Therefore, distributed and sparse codes co-exist in the network units to represent different face attributes. At the ensemble level, principal component analysis of face representations showed that identity, gender, and viewpoint information separated into high-dimensional subspaces, ordered by explained variance. Identity, gender, and viewpoint information contributed to all individual unit responses, undercutting a neural tuning analogy for face attributes. Interpretation of neural-like codes from DCNNs, and by analogy, high-level visual codes, cannot be inferred from single unit responses. Instead, "meaning" is encoded by directions in the high-dimensional space.

Deep Convolutional Neural Networks in the Face of Caricature: Identity and Image Revealed

Dec 28, 2018

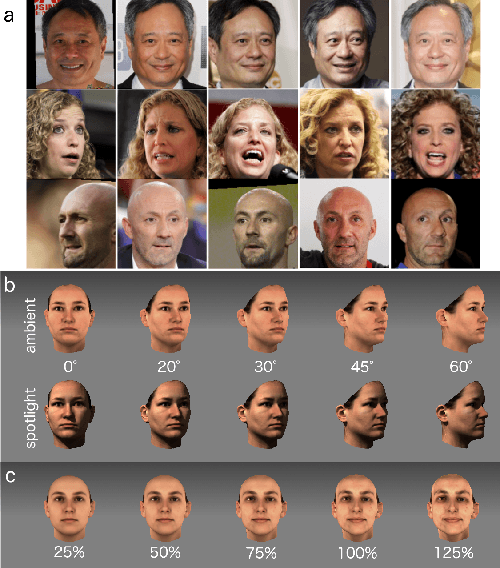

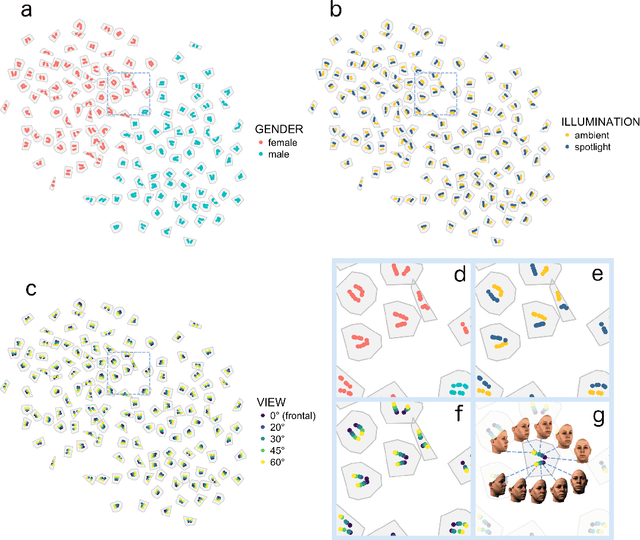

Abstract:Real-world face recognition requires an ability to perceive the unique features of an individual face across multiple, variable images. The primate visual system solves the problem of image invariance using cascades of neurons that convert images of faces into categorical representations of facial identity. Deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) also create generalizable face representations, but with cascades of simulated neurons. DCNN representations can be examined in a multidimensional "face space", with identities and image parameters quantified via their projections onto the axes that define the space. We examined the organization of viewpoint, illumination, gender, and identity in this space. We show that the network creates a highly organized, hierarchically nested, face similarity structure in which information about face identity and imaging characteristics coexist. Natural image variation is accommodated in this hierarchy, with face identity nested under gender, illumination nested under identity, and viewpoint nested under illumination. To examine identity, we caricatured faces and found that network identification accuracy increased with caricature level, and--mimicking human perception--a caricatured distortion of a face "resembled" its veridical counterpart. Caricatures improved performance by moving the identity away from other identities in the face space and minimizing the effects of illumination and viewpoint. Deep networks produce face representations that solve long-standing computational problems in generalized face recognition. They also provide a unitary theoretical framework for reconciling decades of behavioral and neural results that emphasized either the image or the object/face in representations, without understanding how a neural code could seamlessly accommodate both.

Deep Convolutional Neural Network Features and the Original Image

Nov 06, 2016

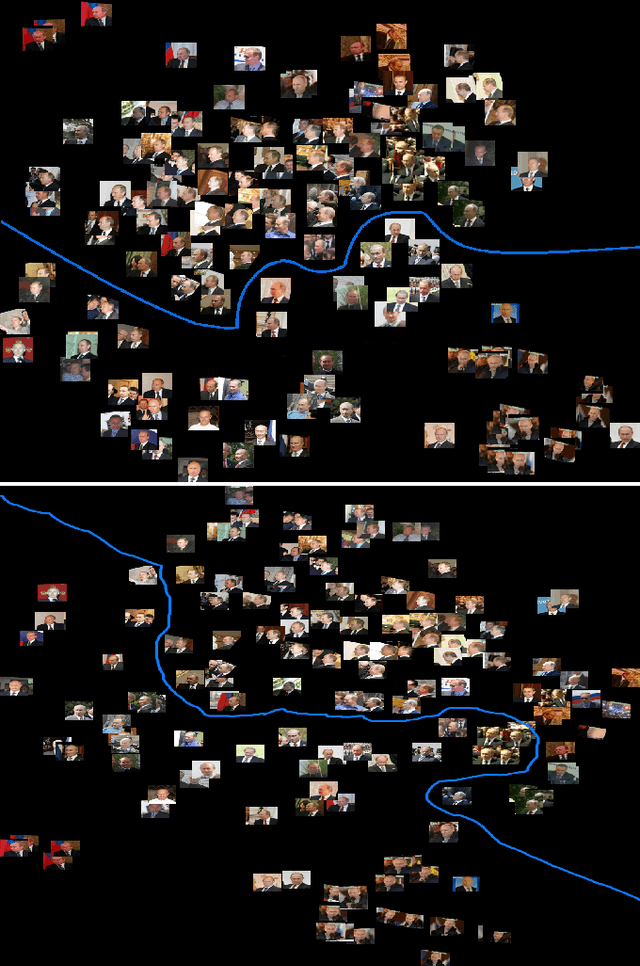

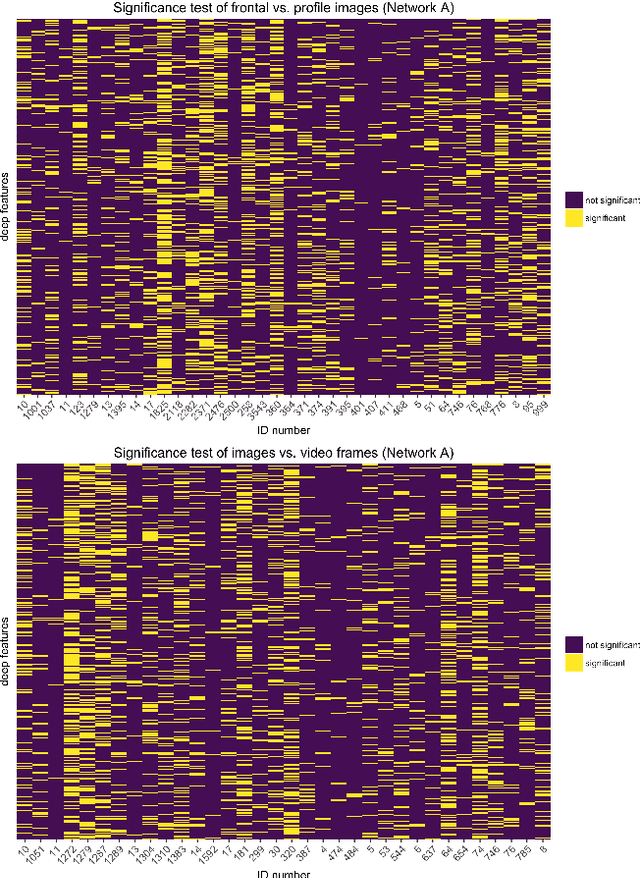

Abstract:Face recognition algorithms based on deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) have made progress on the task of recognizing faces in unconstrained viewing conditions. These networks operate with compact feature-based face representations derived from learning a very large number of face images. While the learned features produced by DCNNs can be highly robust to changes in viewpoint, illumination, and appearance, little is known about the nature of the face code that emerges at the top level of such networks. We analyzed the DCNN features produced by two face recognition algorithms. In the first set of experiments we used the top-level features from the DCNNs as input into linear classifiers aimed at predicting metadata about the images. The results show that the DCNN features contain surprisingly accurate information about the yaw and pitch of a face, and about whether the face came from a still image or a video frame. In the second set of experiments, we measured the extent to which individual DCNN features operated in a view-dependent or view-invariant manner. We found that view-dependent coding was a characteristic of the identities rather than the DCNN features - with some identities coded consistently in a view-dependent way and others in a view-independent way. In our third analysis, we visualized the DCNN feature space for over 24,000 images of 500 identities. Images in the center of the space were uniformly of low quality (e.g., extreme views, face occlusion, low resolution). Image quality increased monotonically as a function of distance from the origin. This result suggests that image quality information is available in the DCNN features, such that consistently average feature values reflect coding failures that reliably indicate poor or unusable images. Combined, the results offer insight into the coding mechanisms that support robust representation of faces in DCNNs.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge