Laura Vianna

Beyond Denouncing Hate: Strategies for Countering Implied Biases and Stereotypes in Language

Oct 31, 2023

Abstract:Counterspeech, i.e., responses to counteract potential harms of hateful speech, has become an increasingly popular solution to address online hate speech without censorship. However, properly countering hateful language requires countering and dispelling the underlying inaccurate stereotypes implied by such language. In this work, we draw from psychology and philosophy literature to craft six psychologically inspired strategies to challenge the underlying stereotypical implications of hateful language. We first examine the convincingness of each of these strategies through a user study, and then compare their usages in both human- and machine-generated counterspeech datasets. Our results show that human-written counterspeech uses countering strategies that are more specific to the implied stereotype (e.g., counter examples to the stereotype, external factors about the stereotype's origins), whereas machine-generated counterspeech uses less specific strategies (e.g., generally denouncing the hatefulness of speech). Furthermore, machine-generated counterspeech often employs strategies that humans deem less convincing compared to human-produced counterspeech. Our findings point to the importance of accounting for the underlying stereotypical implications of speech when generating counterspeech and for better machine reasoning about anti-stereotypical examples.

Annotators with Attitudes: How Annotator Beliefs And Identities Bias Toxic Language Detection

Nov 15, 2021

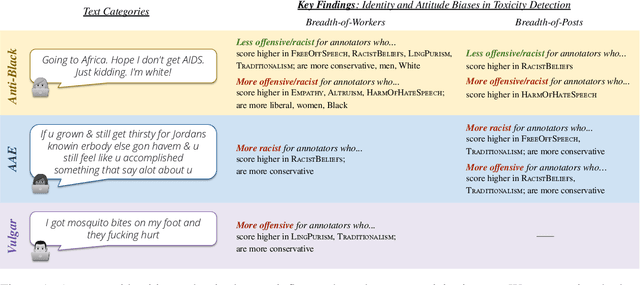

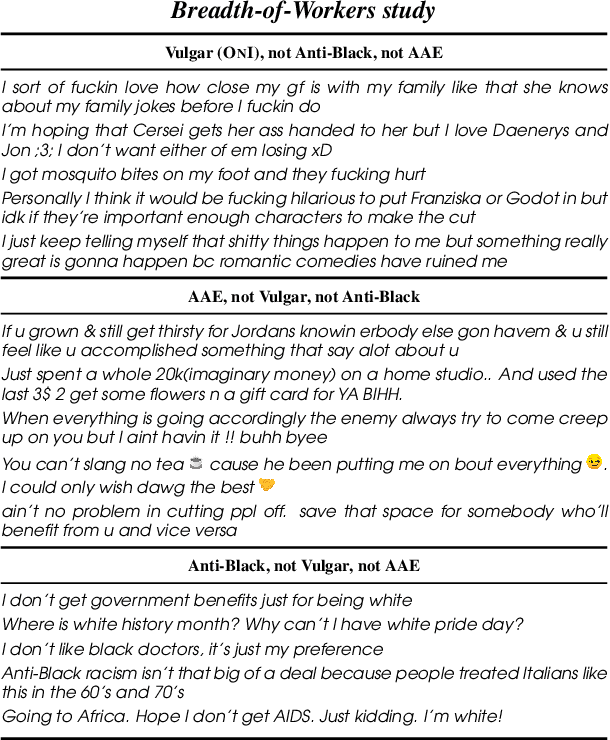

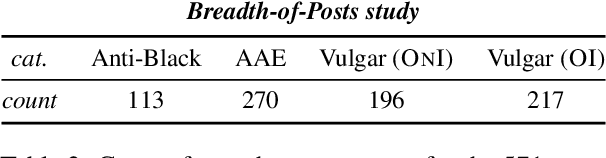

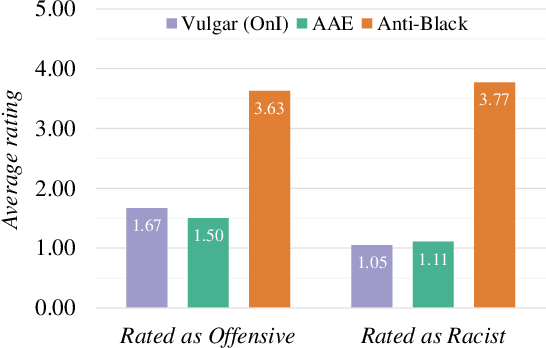

Abstract:The perceived toxicity of language can vary based on someone's identity and beliefs, but this variation is often ignored when collecting toxic language datasets, resulting in dataset and model biases. We seek to understand the who, why, and what behind biases in toxicity annotations. In two online studies with demographically and politically diverse participants, we investigate the effect of annotator identities (who) and beliefs (why), drawing from social psychology research about hate speech, free speech, racist beliefs, political leaning, and more. We disentangle what is annotated as toxic by considering posts with three characteristics: anti-Black language, African American English (AAE) dialect, and vulgarity. Our results show strong associations between annotator identity and beliefs and their ratings of toxicity. Notably, more conservative annotators and those who scored highly on our scale for racist beliefs were less likely to rate anti-Black language as toxic, but more likely to rate AAE as toxic. We additionally present a case study illustrating how a popular toxicity detection system's ratings inherently reflect only specific beliefs and perspectives. Our findings call for contextualizing toxicity labels in social variables, which raises immense implications for toxic language annotation and detection.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge