Herman Veluwenkamp

Measuring the right thing: justifying metrics in AI impact assessments

Apr 07, 2025Abstract:AI Impact Assessments are only as good as the measures used to assess the impact of these systems. It is therefore paramount that we can justify our choice of metrics in these assessments, especially for difficult to quantify ethical and social values. We present a two-step approach to ensure metrics are properly motivated. First, a conception needs to be spelled out (e.g. Rawlsian fairness or fairness as solidarity) and then a metric can be fitted to that conception. Both steps require separate justifications, as conceptions can be judged on how well they fit with the function of, for example, fairness. We argue that conceptual engineering offers helpful tools for this step. Second, metrics need to be fitted to a conception. We illustrate this process through an examination of competing fairness metrics to illustrate that here the additional content that a conception offers helps us justify the choice for a specific metric. We thus advocate that impact assessments are not only clear on their metrics, but also on the conceptions that motivate those metrics.

Meaningful human control over AI systems: beyond talking the talk

Nov 25, 2021

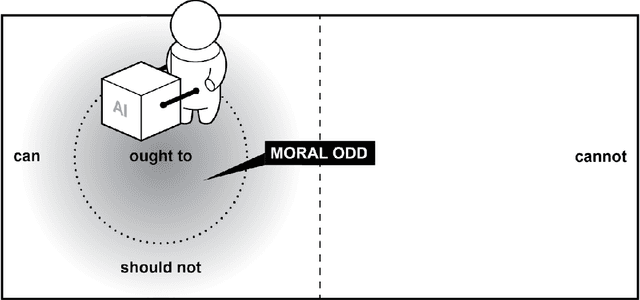

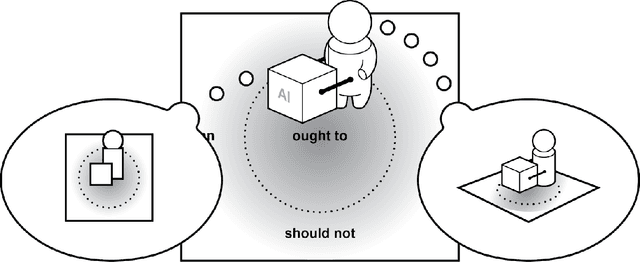

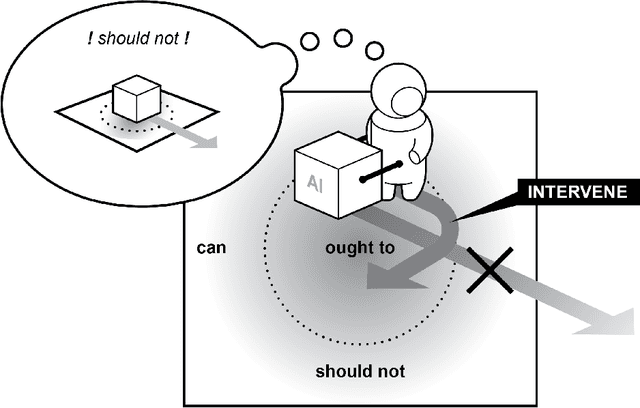

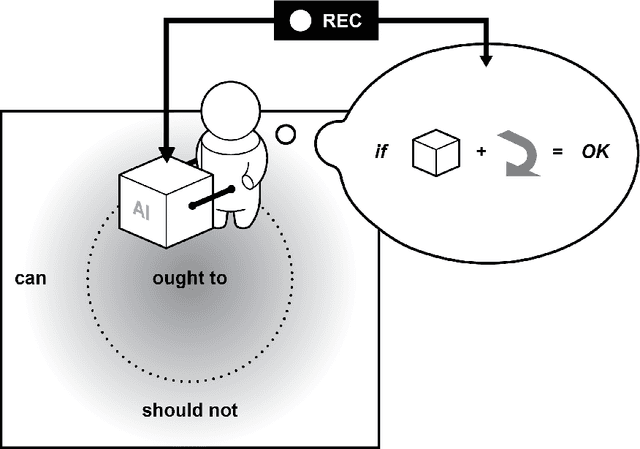

Abstract:The concept of meaningful human control has been proposed to address responsibility gaps and mitigate them by establishing conditions that enable a proper attribution of responsibility for humans (e.g., users, designers and developers, manufacturers, legislators). However, the relevant discussions around meaningful human control have so far not resulted in clear requirements for researchers, designers, and engineers. As a result, there is no consensus on how to assess whether a designed AI system is under meaningful human control, making the practical development of AI-based systems that remain under meaningful human control challenging. In this paper, we address the gap between philosophical theory and engineering practice by identifying four actionable properties which AI-based systems must have to be under meaningful human control. First, a system in which humans and AI algorithms interact should have an explicitly defined domain of morally loaded situations within which the system ought to operate. Second, humans and AI agents within the system should have appropriate and mutually compatible representations. Third, responsibility attributed to a human should be commensurate with that human's ability and authority to control the system. Fourth, there should be explicit links between the actions of the AI agents and actions of humans who are aware of their moral responsibility. We argue these four properties are necessary for AI systems under meaningful human control, and provide possible directions to incorporate them into practice. We illustrate these properties with two use cases, automated vehicle and AI-based hiring. We believe these four properties will support practically-minded professionals to take concrete steps toward designing and engineering for AI systems that facilitate meaningful human control and responsibility.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge