David Abbink

Can a mobile robot learn from a pedestrian model to prevent the sidewalk salsa?

Aug 29, 2025Abstract:Pedestrians approaching each other on a sidewalk sometimes end up in an awkward interaction known as the "sidewalk salsa": they both (repeatedly) deviate to the same side to avoid a collision. This provides an interesting use case to study interactions between pedestrians and mobile robots because, in the vast majority of cases, this phenomenon is avoided through a negotiation based on implicit communication. Understanding how it goes wrong and how pedestrians end up in the sidewalk salsa will therefore provide insight into the implicit communication. This understanding can be used to design safe and acceptable robotic behaviour. In a previous attempt to gain this understanding, a model of pedestrian behaviour based on the Communication-Enabled Interaction (CEI) framework was developed that can replicate the sidewalk salsa. However, it is unclear how to leverage this model in robotic planning and decision-making since it violates the assumptions of game theory, a much-used framework in planning and decision-making. Here, we present a proof-of-concept for an approach where a Reinforcement Learning (RL) agent leverages the model to learn how to interact with pedestrians. The results show that a basic RL agent successfully learned to interact with the CEI model. Furthermore, a risk-averse RL agent that had access to the perceived risk of the CEI model learned how to effectively communicate its intention through its motion and thereby substantially lowered the perceived risk, and displayed effort by the modelled pedestrian. These results show this is a promising approach and encourage further exploration.

Haptic Shared Control for Dissipating Phantom Traffic Jams

Dec 22, 2022Abstract:Traffic jams occurring on highways cause increased travel time as well as increased fuel consumption and collisions. Traffic jams without a clear cause, such as an on-ramp or an accident, are called phantom traffic jams and are said to make up 50% of all traffic jams. They are the result of an unstable traffic flow caused by human driving behavior. Automating the longitudinal vehicle motion of only 5% of all cars in the flow can dissipate phantom traffic jams. However, driving automation introduces safety issues when human drivers need to take over the control from the automation. We investigated whether phantom traffic jams can be dissolved using haptic shared control. This keeps humans in the loop and thus bypasses the problem of humans' limited capacity to take over control, while benefiting from most advantages of automation. In an experiment with 24 participants in a driving simulator, we tested the effect of haptic shared control on the dynamics of traffic flow, and compared it with manual control and full automation. We also investigated the effect of two control types on participants' behavior during simulated silent automation failures. Results show that haptic shared control can help dissipating phantom traffic jams better than fully manual control but worse than full automation. We also found that haptic shared control reduces the occurrence of unsafe situations caused by silent automation failures compared to full automation. Our results suggest that haptic shared control can dissipate phantom traffic jams while preventing safety risks associated with full automation.

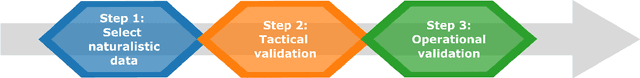

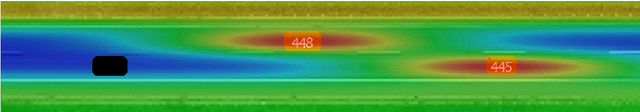

Automatic extraction of similar traffic scenes from large naturalistic datasets using the Hausdorff distance

Jun 17, 2022

Abstract:Recently, multiple naturalistic traffic datasets of human-driven trajectories have been published (e.g., highD, NGSim, and pNEUMA). These datasets have been used in studies that investigate variability in human driving behavior, for example for scenario-based validation of autonomous vehicle (AV) behavior, modeling driver behavior, or validating driver models. Thus far, these studies focused on the variability on an operational level (e.g., velocity profiles during a lane change), not on a tactical level (i.e., to change lanes or not). Investigating the variability on both levels is necessary to develop driver models and AVs that include multiple tactical behaviors. To expose multi-level variability, the human responses to the same traffic scene could be investigated. However, no method exists to automatically extract similar scenes from datasets. Here, we present a four-step extraction method that uses the Hausdorff distance, a mathematical distance metric for sets. We performed a case study on the highD dataset that showed that the method is practically applicable. The human responses to the selected scenes exposed the variability on both the tactical and operational levels. With this new method, the variability in operational and tactical human behavior can be investigated, without the need for costly and time-consuming driving-simulator experiments.

Meaningful human control over AI systems: beyond talking the talk

Nov 25, 2021

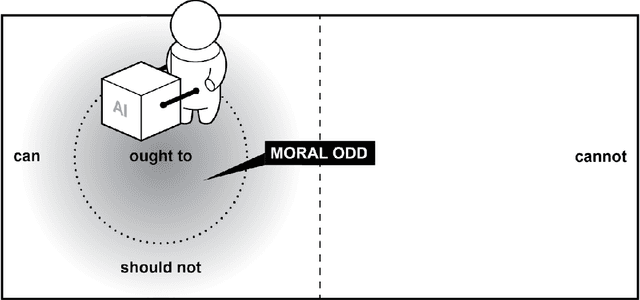

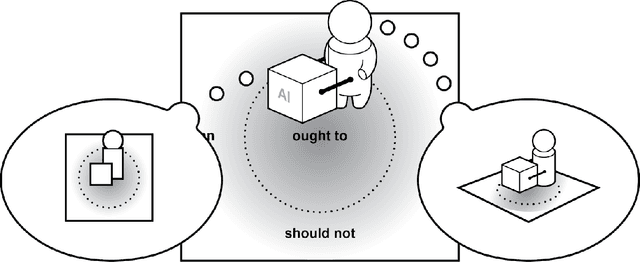

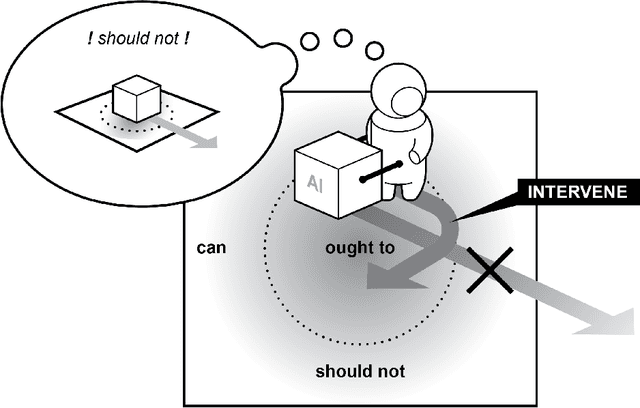

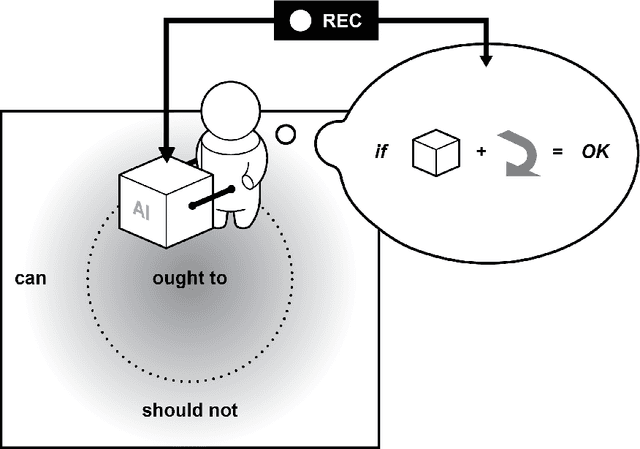

Abstract:The concept of meaningful human control has been proposed to address responsibility gaps and mitigate them by establishing conditions that enable a proper attribution of responsibility for humans (e.g., users, designers and developers, manufacturers, legislators). However, the relevant discussions around meaningful human control have so far not resulted in clear requirements for researchers, designers, and engineers. As a result, there is no consensus on how to assess whether a designed AI system is under meaningful human control, making the practical development of AI-based systems that remain under meaningful human control challenging. In this paper, we address the gap between philosophical theory and engineering practice by identifying four actionable properties which AI-based systems must have to be under meaningful human control. First, a system in which humans and AI algorithms interact should have an explicitly defined domain of morally loaded situations within which the system ought to operate. Second, humans and AI agents within the system should have appropriate and mutually compatible representations. Third, responsibility attributed to a human should be commensurate with that human's ability and authority to control the system. Fourth, there should be explicit links between the actions of the AI agents and actions of humans who are aware of their moral responsibility. We argue these four properties are necessary for AI systems under meaningful human control, and provide possible directions to incorporate them into practice. We illustrate these properties with two use cases, automated vehicle and AI-based hiring. We believe these four properties will support practically-minded professionals to take concrete steps toward designing and engineering for AI systems that facilitate meaningful human control and responsibility.

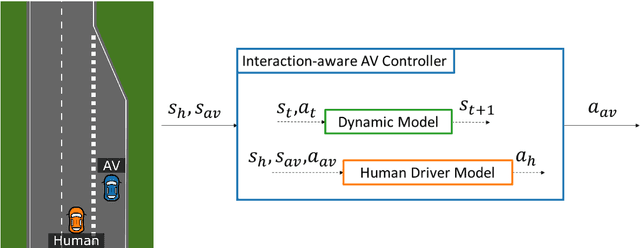

Validating human driver models for interaction-aware automated vehicle controllers: A human factors approach

Sep 27, 2021

Abstract:A major challenge for autonomous vehicles is interacting with other traffic participants safely and smoothly. A promising approach to handle such traffic interactions is equipping autonomous vehicles with interaction-aware controllers (IACs). These controllers predict how surrounding human drivers will respond to the autonomous vehicle's actions, based on a driver model. However, the predictive validity of driver models used in IACs is rarely validated, which can limit the interactive capabilities of IACs outside the simple simulated environments in which they are demonstrated. In this paper, we argue that besides evaluating the interactive capabilities of IACs, their underlying driver models should be validated on natural human driving behavior. We propose a workflow for this validation that includes scenario-based data extraction and a two-stage (tactical/operational) evaluation procedure based on human factors literature. We demonstrate this workflow in a case study on an inverse-reinforcement-learning-based driver model replicated from an existing IAC. This model only showed the correct tactical behavior in 40% of the predictions. The model's operational behavior was inconsistent with observed human behavior. The case study illustrates that a principled evaluation workflow is useful and needed. We believe that our workflow will support the development of appropriate driver models for future automated vehicles.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge