Hélène Sauzéon

Inria FLOWERS team Talence France, Université de Bordeaux BPH lab Bordeaux France

Improved Performances and Motivation in Intelligent Tutoring Systems: Combining Machine Learning and Learner Choice

Jan 16, 2024Abstract:Large class sizes pose challenges to personalized learning in schools, which educational technologies, especially intelligent tutoring systems (ITS), aim to address. In this context, the ZPDES algorithm, based on the Learning Progress Hypothesis (LPH) and multi-armed bandit machine learning techniques, sequences exercises that maximize learning progress (LP). This algorithm was previously shown in field studies to boost learning performances for a wider diversity of students compared to a hand-designed curriculum. However, its motivational impact was not assessed. Also, ZPDES did not allow students to express choices. This limitation in agency is at odds with the LPH theory concerned with modeling curiosity-driven learning. We here study how the introduction of such choice possibilities impact both learning efficiency and motivation. The given choice concerns dimensions that are orthogonal to exercise difficulty, acting as a playful feature. In an extensive field study (265 7-8 years old children, RCT design), we compare systems based either on ZPDES or a hand-designed curriculum, both with and without self-choice. We first show that ZPDES improves learning performance and produces a positive and motivating learning experience. We then show that the addition of choice triggers intrinsic motivation and reinforces the learning effectiveness of the LP-based personalization. In doing so, it strengthens the links between intrinsic motivation and performance progress during the serious game. Conversely, deleterious effects of the playful feature are observed for hand-designed linear paths. Thus, the intrinsic motivation elicited by a playful feature is beneficial only if the curriculum personalization is effective for the learner. Such a result deserves great attention due to increased use of playful features in non adaptive educational technologies.

GPT-3-driven pedagogical agents for training children's curious question-asking skills

Dec 08, 2022Abstract:Students' ability to ask curious questions is a crucial skill that improves their learning processes. To train this skill, previous research has used a conversational agent that propose specific cues to prompt children's curiosity during learning. Despite showing pedagogical efficiency, this method is still limited since it relies on generating the said prompts by hand for each educational resource, which can be a very long and costly process. In this context, we leverage the advances in the natural language processing field and explore using a large language model (GPT-3) to automate the generation of this agent's curiosity-prompting cues to help children ask more and deeper questions. We then used this study to investigate a different curiosity-prompting behavior for the agent. The study was conducted with 75 students aged between 9 and 10. They either interacted with a hand-crafted conversational agent that proposes "closed" manually-extracted cues leading to predefined questions, a GPT-3-driven one that proposes the same type of cues, or a GPT-3-driven one that proposes "open" cues that can lead to several possible questions. Results showed a similar question-asking performance between children who had the two "closed" agents, but a significantly better one for participants with the "open" agent. Our first results suggest the validity of using GPT-3 to facilitate the implementation of curiosity-stimulating learning technologies. In a second step, we also show that GPT-3 can be efficient in proposing the relevant open cues that leave children with more autonomy to express their curiosity.

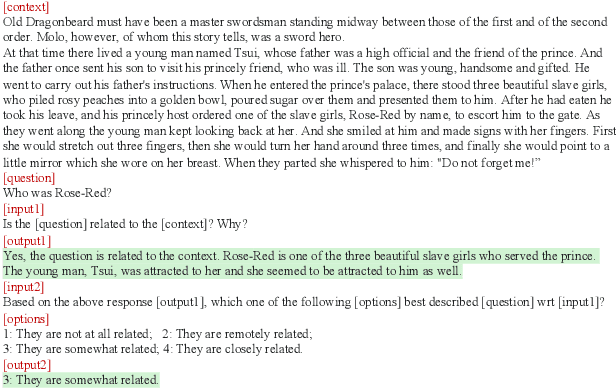

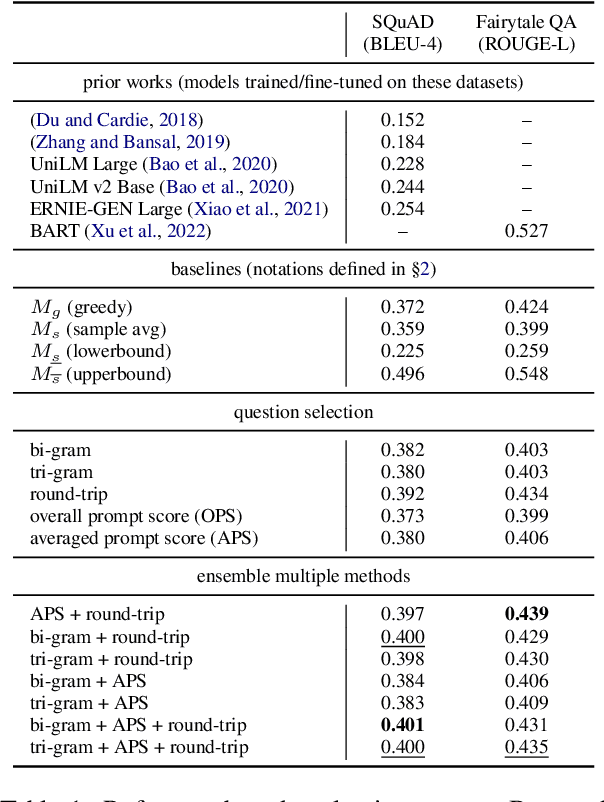

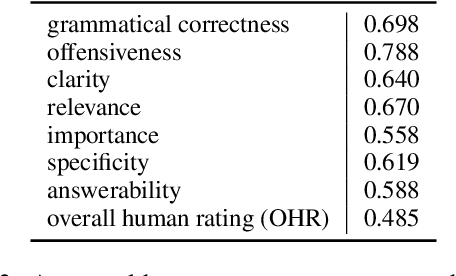

Selecting Better Samples from Pre-trained LLMs: A Case Study on Question Generation

Sep 22, 2022

Abstract:Large Language Models (LLMs) have in recent years demonstrated impressive prowess in natural language generation. A common practice to improve generation diversity is to sample multiple outputs from the model. However, there lacks a simple and robust way of selecting the best output from these stochastic samples. As a case study framed in the context of question generation, we propose two prompt-based approaches to selecting high-quality questions from a set of LLM-generated candidates. Our method works under the constraints of 1) a black-box (non-modifiable) question generation model and 2) lack of access to human-annotated references -- both of which are realistic limitations for real-world deployment of LLMs. With automatic as well as human evaluations, we empirically demonstrate that our approach can effectively select questions of higher qualities than greedy generation.

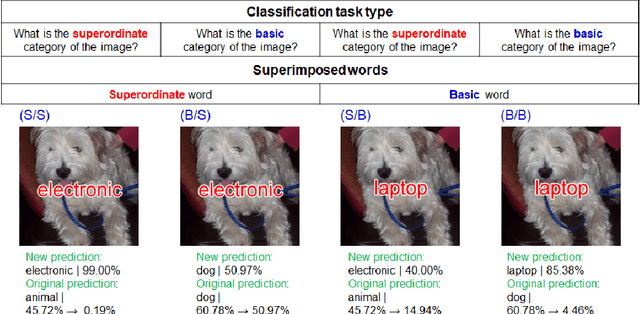

Evaluating language-biased image classification based on semantic representations

Jan 26, 2022

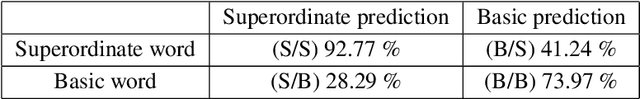

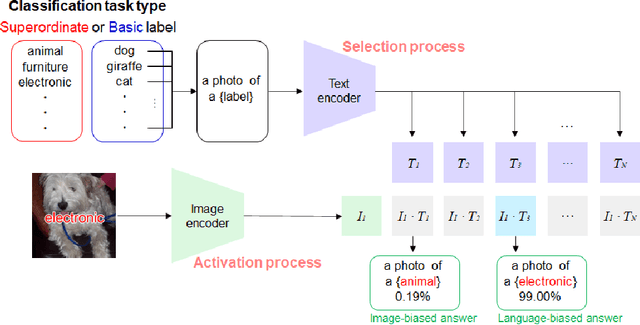

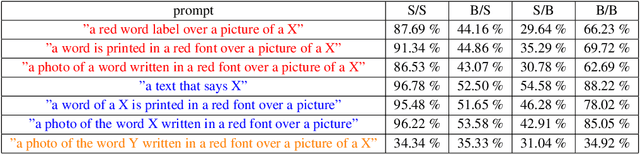

Abstract:Humans show language-biased image recognition for a word-embedded image, known as picture-word interference. Such interference depends on hierarchical semantic categories and reflects that human language processing highly interacts with visual processing. Similar to humans, recent artificial models jointly trained on texts and images, e.g., OpenAI CLIP, show language-biased image classification. Exploring whether the bias leads to interferences similar to those observed in humans can contribute to understanding how much the model acquires hierarchical semantic representations from joint learning of language and vision. The present study introduces methodological tools from the cognitive science literature to assess the biases of artificial models. Specifically, we introduce a benchmark task to test whether words superimposed on images can distort the image classification across different category levels and, if it can, whether the perturbation is due to the shared semantic representation between language and vision. Our dataset is a set of word-embedded images and consists of a mixture of natural image datasets and hierarchical word labels with superordinate/basic category levels. Using this benchmark test, we evaluate the CLIP model. We show that presenting words distorts the image classification by the model across different category levels, but the effect does not depend on the semantic relationship between images and embedded words. This suggests that the semantic word representation in the CLIP visual processing is not shared with the image representation, although the word representation strongly dominates for word-embedded images.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge