Nina Grgic-Hlaca

MPI-SWS

An Empirical Study on Learning Fairness Metrics for COMPAS Data with Human Supervision

Oct 31, 2019

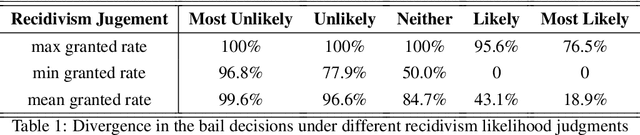

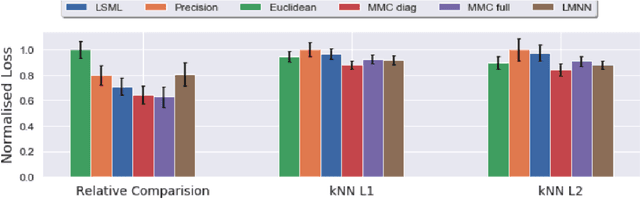

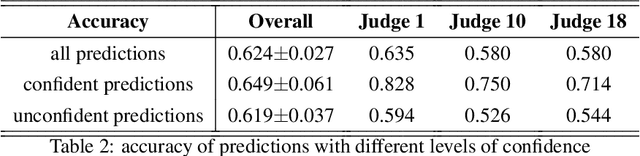

Abstract:The notion of individual fairness requires that similar people receive similar treatment. However, this is hard to achieve in practice since it is difficult to specify the appropriate similarity metric. In this work, we attempt to learn such similarity metric from human annotated data. We gather a new dataset of human judgments on a criminal recidivism prediction (COMPAS) task. By assuming the human supervision obeys the principle of individual fairness, we leverage prior work on metric learning, evaluate the performance of several metric learning methods on our dataset, and show that the learned metrics outperform the Euclidean and Precision metric under various criteria. We do not provide a way to directly learn a similarity metric satisfying the individual fairness, but to provide an empirical study on how to derive the similarity metric from human supervisors, then future work can use this as a tool to understand human supervision.

A Unified Approach to Quantifying Algorithmic Unfairness: Measuring Individual & Group Unfairness via Inequality Indices

Jul 02, 2018

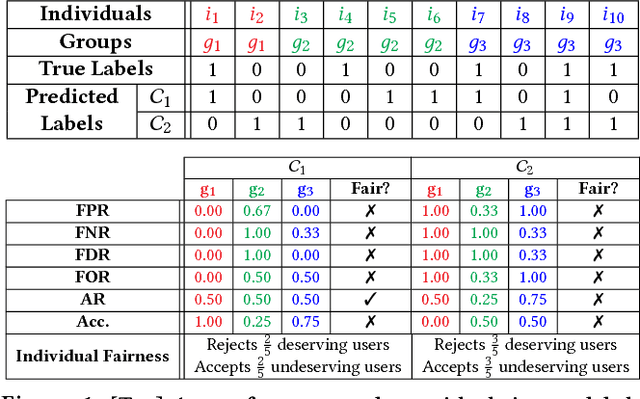

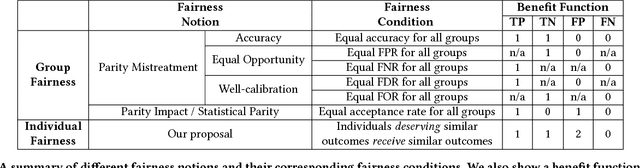

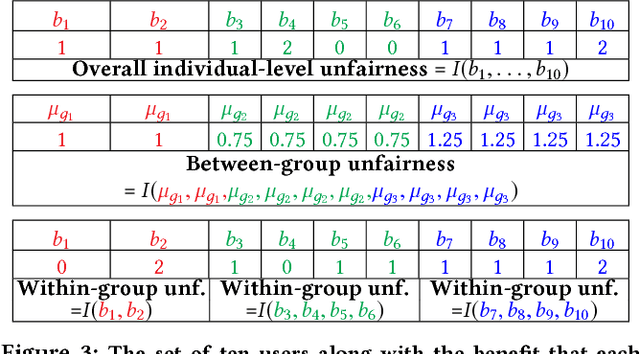

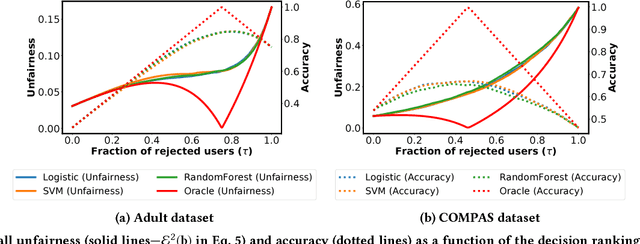

Abstract:Discrimination via algorithmic decision making has received considerable attention. Prior work largely focuses on defining conditions for fairness, but does not define satisfactory measures of algorithmic unfairness. In this paper, we focus on the following question: Given two unfair algorithms, how should we determine which of the two is more unfair? Our core idea is to use existing inequality indices from economics to measure how unequally the outcomes of an algorithm benefit different individuals or groups in a population. Our work offers a justified and general framework to compare and contrast the (un)fairness of algorithmic predictors. This unifying approach enables us to quantify unfairness both at the individual and the group level. Further, our work reveals overlooked tradeoffs between different fairness notions: using our proposed measures, the overall individual-level unfairness of an algorithm can be decomposed into a between-group and a within-group component. Earlier methods are typically designed to tackle only between-group unfairness, which may be justified for legal or other reasons. However, we demonstrate that minimizing exclusively the between-group component may, in fact, increase the within-group, and hence the overall unfairness. We characterize and illustrate the tradeoffs between our measures of (un)fairness and the prediction accuracy.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge