Nathan Cloos

AI Gamestore: Scalable, Open-Ended Evaluation of Machine General Intelligence with Human Games

Feb 19, 2026Abstract:Rigorously evaluating machine intelligence against the broad spectrum of human general intelligence has become increasingly important and challenging in this era of rapid technological advance. Conventional AI benchmarks typically assess only narrow capabilities in a limited range of human activity. Most are also static, quickly saturating as developers explicitly or implicitly optimize for them. We propose that a more promising way to evaluate human-like general intelligence in AI systems is through a particularly strong form of general game playing: studying how and how well they play and learn to play \textbf{all conceivable human games}, in comparison to human players with the same level of experience, time, or other resources. We define a "human game" to be a game designed by humans for humans, and argue for the evaluative suitability of this space of all such games people can imagine and enjoy -- the "Multiverse of Human Games". Taking a first step towards this vision, we introduce the AI GameStore, a scalable and open-ended platform that uses LLMs with humans-in-the-loop to synthesize new representative human games, by automatically sourcing and adapting standardized and containerized variants of game environments from popular human digital gaming platforms. As a proof of concept, we generated 100 such games based on the top charts of Apple App Store and Steam, and evaluated seven frontier vision-language models (VLMs) on short episodes of play. The best models achieved less than 10\% of the human average score on the majority of the games, and especially struggled with games that challenge world-model learning, memory and planning. We conclude with a set of next steps for building out the AI GameStore as a practical way to measure and drive progress toward human-like general intelligence in machines.

A Framework for Standardizing Similarity Measures in a Rapidly Evolving Field

Sep 26, 2024Abstract:Similarity measures are fundamental tools for quantifying the alignment between artificial and biological systems. However, the diversity of similarity measures and their varied naming and implementation conventions makes it challenging to compare across studies. To facilitate comparisons and make explicit the implementation choices underlying a given code package, we have created and are continuing to develop a Python repository that benchmarks and standardizes similarity measures. The goal of creating a consistent naming convention that uniquely and efficiently specifies a similarity measure is not trivial as, for example, even commonly used methods like Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA) have at least 12 different variations, and this number will likely continue to grow as the field evolves. For this reason, we do not advocate for a fixed, definitive naming convention. The landscape of similarity measures and best practices will continue to change and so we see our current repository, which incorporates approximately 100 different similarity measures from 14 packages, as providing a useful tool at this snapshot in time. To accommodate the evolution of the field we present a framework for developing, validating, and refining naming conventions with the goal of uniquely and efficiently specifying similarity measures, ultimately making it easier for the community to make comparisons across studies.

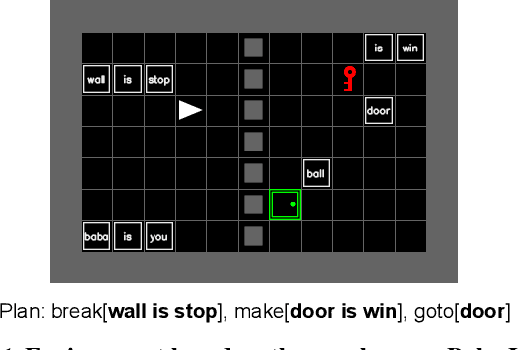

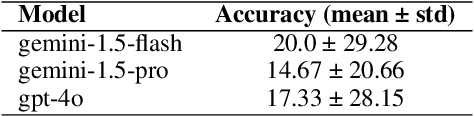

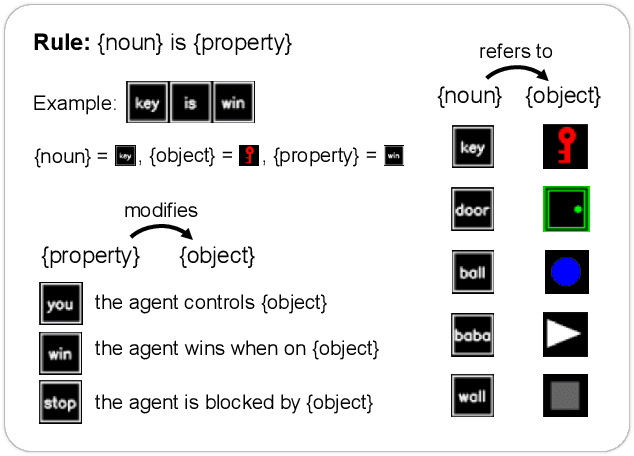

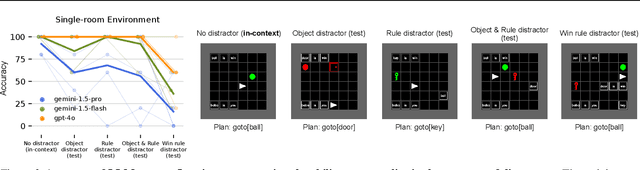

Baba Is AI: Break the Rules to Beat the Benchmark

Jul 18, 2024

Abstract:Humans solve problems by following existing rules and procedures, and also by leaps of creativity to redefine those rules and objectives. To probe these abilities, we developed a new benchmark based on the game Baba Is You where an agent manipulates both objects in the environment and rules, represented by movable tiles with words written on them, to reach a specified goal and win the game. We test three state-of-the-art multi-modal large language models (OpenAI GPT-4o, Google Gemini-1.5-Pro and Gemini-1.5-Flash) and find that they fail dramatically when generalization requires that the rules of the game must be manipulated and combined.

Differentiable Optimization of Similarity Scores Between Models and Brains

Jul 09, 2024Abstract:What metrics should guide the development of more realistic models of the brain? One proposal is to quantify the similarity between models and brains using methods such as linear regression, Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA), and angular Procrustes distance. To better understand the limitations of these similarity measures we analyze neural activity recorded in five experiments on nonhuman primates, and optimize synthetic datasets to become more similar to these neural recordings. How similar can these synthetic datasets be to neural activity while failing to encode task relevant variables? We find that some measures like linear regression and CKA, differ from angular Procrustes, and yield high similarity scores even when task relevant variables cannot be linearly decoded from the synthetic datasets. Synthetic datasets optimized to maximize similarity scores initially learn the first principal component of the target dataset, but angular Procrustes captures higher variance dimensions much earlier than methods like linear regression and CKA. We show in both theory and simulations how these scores change when different principal components are perturbed. And finally, we jointly optimize multiple similarity scores to find their allowed ranges, and show that a high angular Procrustes similarity, for example, implies a high CKA score, but not the converse.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge