Learning Optimal Advantage from Preferences and Mistaking it for Reward

Paper and Code

Oct 03, 2023

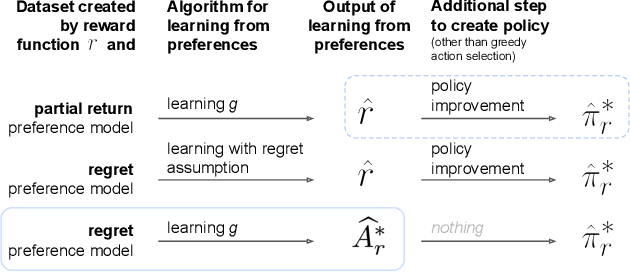

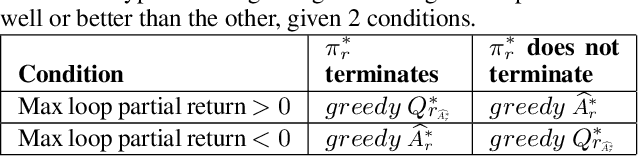

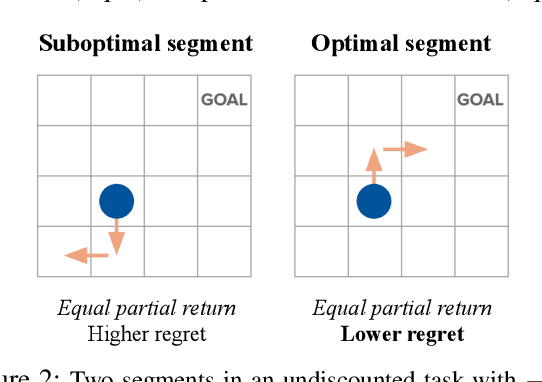

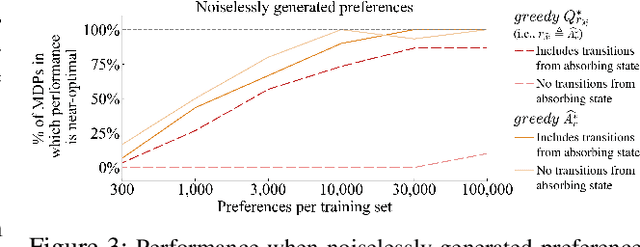

We consider algorithms for learning reward functions from human preferences over pairs of trajectory segments, as used in reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). Most recent work assumes that human preferences are generated based only upon the reward accrued within those segments, or their partial return. Recent work casts doubt on the validity of this assumption, proposing an alternative preference model based upon regret. We investigate the consequences of assuming preferences are based upon partial return when they actually arise from regret. We argue that the learned function is an approximation of the optimal advantage function, $\hat{A^*_r}$, not a reward function. We find that if a specific pitfall is addressed, this incorrect assumption is not particularly harmful, resulting in a highly shaped reward function. Nonetheless, this incorrect usage of $\hat{A^*_r}$ is less desirable than the appropriate and simpler approach of greedy maximization of $\hat{A^*_r}$. From the perspective of the regret preference model, we also provide a clearer interpretation of fine tuning contemporary large language models with RLHF. This paper overall provides insight regarding why learning under the partial return preference model tends to work so well in practice, despite it conforming poorly to how humans give preferences.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge