Vibhhu Sharma

Do LLMs Favor LLMs? Quantifying Interaction Effects in Peer Review

Jan 28, 2026Abstract:There are increasing indications that LLMs are not only used for producing scientific papers, but also as part of the peer review process. In this work, we provide the first comprehensive analysis of LLM use across the peer review pipeline, with particular attention to interaction effects: not just whether LLM-assisted papers or LLM-assisted reviews are different in isolation, but whether LLM-assisted reviews evaluate LLM-assisted papers differently. In particular, we analyze over 125,000 paper-review pairs from ICLR, NeurIPS, and ICML. We initially observe what appears to be a systematic interaction effect: LLM-assisted reviews seem especially kind to LLM-assisted papers compared to papers with minimal LLM use. However, controlling for paper quality reveals a different story: LLM-assisted reviews are simply more lenient toward lower quality papers in general, and the over-representation of LLM-assisted papers among weaker submissions creates a spurious interaction effect rather than genuine preferential treatment of LLM-generated content. By augmenting our observational findings with reviews that are fully LLM-generated, we find that fully LLM-generated reviews exhibit severe rating compression that fails to discriminate paper quality, while human reviewers using LLMs substantially reduce this leniency. Finally, examining metareviews, we find that LLM-assisted metareviews are more likely to render accept decisions than human metareviews given equivalent reviewer scores, though fully LLM-generated metareviews tend to be harsher. This suggests that meta-reviewers do not merely outsource the decision-making to the LLM. These findings provide important input for developing policies that govern the use of LLMs during peer review, and they more generally indicate how LLMs interact with existing decision-making processes.

Comparing Targeting Strategies for Maximizing Social Welfare with Limited Resources

Nov 11, 2024

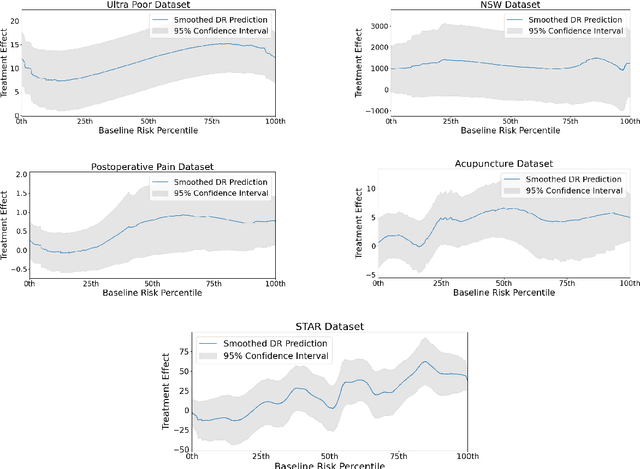

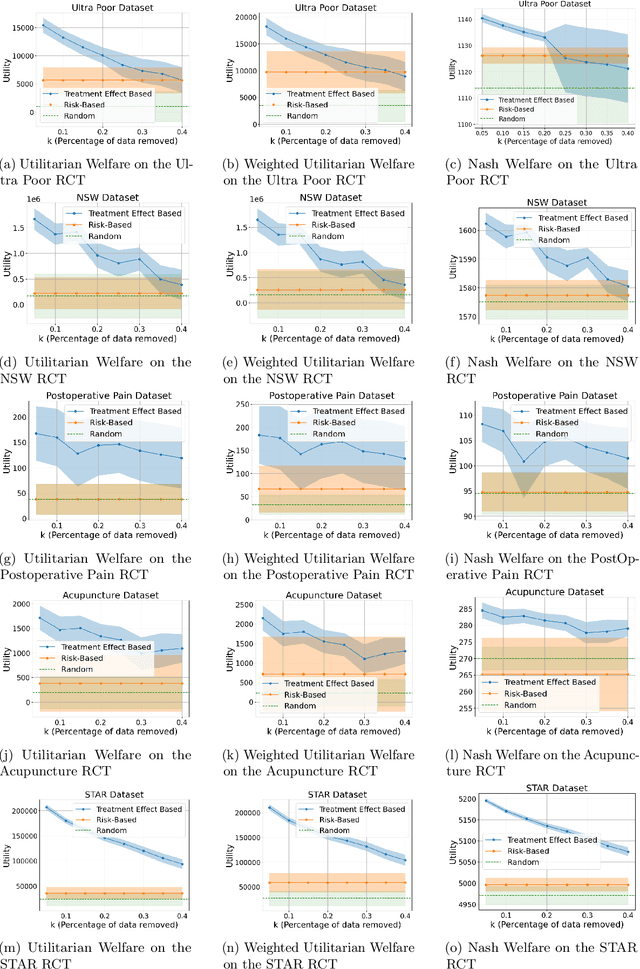

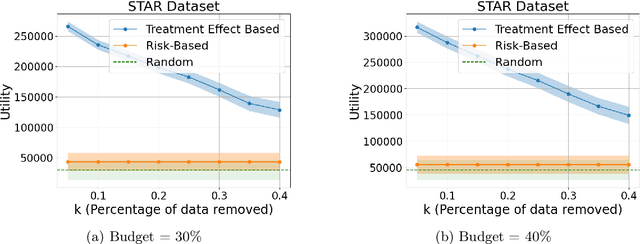

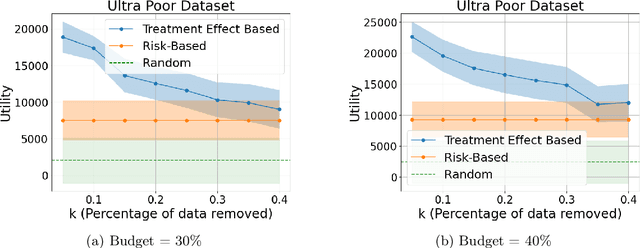

Abstract:Machine learning is increasingly used to select which individuals receive limited-resource interventions in domains such as human services, education, development, and more. However, it is often not apparent what the right quantity is for models to predict. In particular, policymakers rarely have access to data from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that would enable accurate estimates of treatment effects -- which individuals would benefit more from the intervention. Observational data is more likely to be available, creating a substantial risk of bias in treatment effect estimates. Practitioners instead commonly use a technique termed "risk-based targeting" where the model is just used to predict each individual's status quo outcome (an easier, non-causal task). Those with higher predicted risk are offered treatment. There is currently almost no empirical evidence to inform which choices lead to the most effect machine learning-informed targeting strategies in social domains. In this work, we use data from 5 real-world RCTs in a variety of domains to empirically assess such choices. We find that risk-based targeting is almost always inferior to targeting based on even biased estimates of treatment effects. Moreover, these results hold even when the policymaker has strong normative preferences for assisting higher-risk individuals. Our results imply that, despite the widespread use of risk prediction models in applied settings, practitioners may be better off incorporating even weak evidence about heterogeneous causal effects to inform targeting.

Accounting for Missing Covariates in Heterogeneous Treatment Estimation

Oct 21, 2024

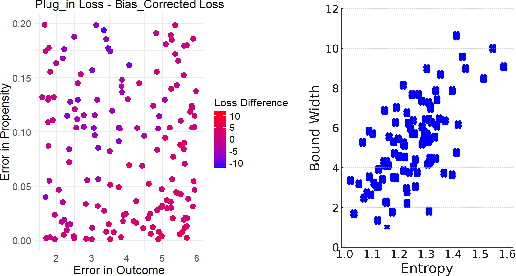

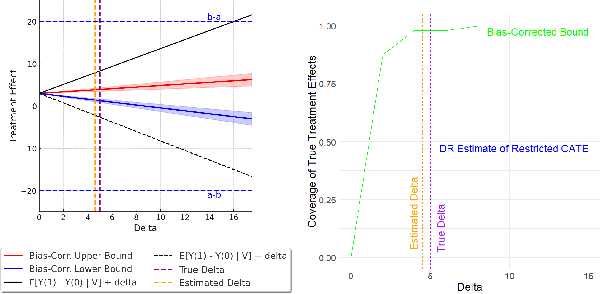

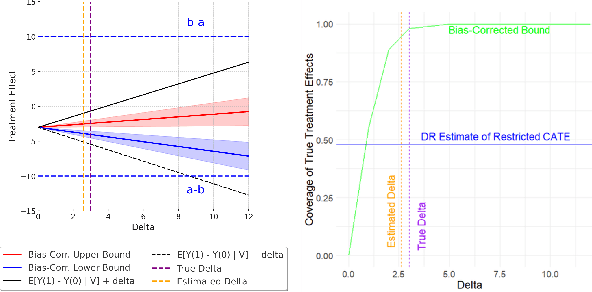

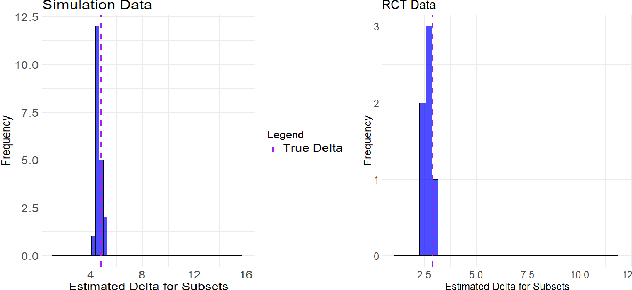

Abstract:Many applications of causal inference require using treatment effects estimated on a study population to make decisions in a separate target population. We consider the challenging setting where there are covariates that are observed in the target population that were not seen in the original study. Our goal is to estimate the tightest possible bounds on heterogeneous treatment effects conditioned on such newly observed covariates. We introduce a novel partial identification strategy based on ideas from ecological inference; the main idea is that estimates of conditional treatment effects for the full covariate set must marginalize correctly when restricted to only the covariates observed in both populations. Furthermore, we introduce a bias-corrected estimator for these bounds and prove that it enjoys fast convergence rates and statistical guarantees (e.g., asymptotic normality). Experimental results on both real and synthetic data demonstrate that our framework can produce bounds that are much tighter than would otherwise be possible.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge