Gabriel Lima

Laypeople's Attitudes Towards Fair, Affirmative, and Discriminatory Decision-Making Algorithms

May 12, 2025Abstract:Affirmative algorithms have emerged as a potential answer to algorithmic discrimination, seeking to redress past harms and rectify the source of historical injustices. We present the results of two experiments ($N$$=$$1193$) capturing laypeople's perceptions of affirmative algorithms -- those which explicitly prioritize the historically marginalized -- in hiring and criminal justice. We contrast these opinions about affirmative algorithms with folk attitudes towards algorithms that prioritize the privileged (i.e., discriminatory) and systems that make decisions independently of demographic groups (i.e., fair). We find that people -- regardless of their political leaning and identity -- view fair algorithms favorably and denounce discriminatory systems. In contrast, we identify disagreements concerning affirmative algorithms: liberals and racial minorities rate affirmative systems as positively as their fair counterparts, whereas conservatives and those from the dominant racial group evaluate affirmative algorithms as negatively as discriminatory systems. We identify a source of these divisions: people have varying beliefs about who (if anyone) is marginalized, shaping their views of affirmative algorithms. We discuss the possibility of bridging these disagreements to bring people together towards affirmative algorithms.

Blaming Humans and Machines: What Shapes People's Reactions to Algorithmic Harm

Apr 05, 2023

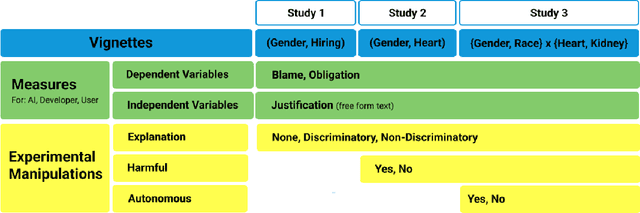

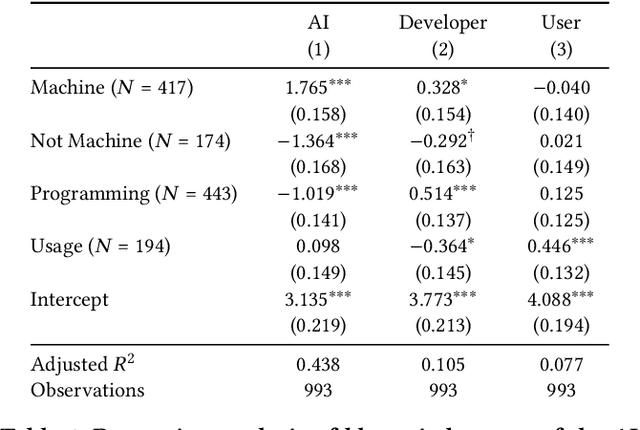

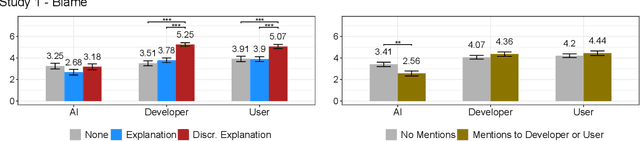

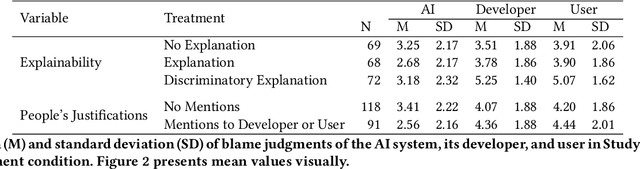

Abstract:Artificial intelligence (AI) systems can cause harm to people. This research examines how individuals react to such harm through the lens of blame. Building upon research suggesting that people blame AI systems, we investigated how several factors influence people's reactive attitudes towards machines, designers, and users. The results of three studies (N = 1,153) indicate differences in how blame is attributed to these actors. Whether AI systems were explainable did not impact blame directed at them, their developers, and their users. Considerations about fairness and harmfulness increased blame towards designers and users but had little to no effect on judgments of AI systems. Instead, what determined people's reactive attitudes towards machines was whether people thought blaming them would be a suitable response to algorithmic harm. We discuss implications, such as how future decisions about including AI systems in the social and moral spheres will shape laypeople's reactions to AI-caused harm.

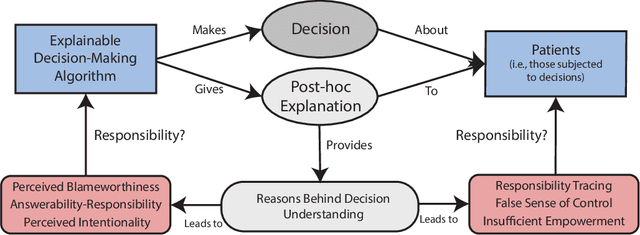

The Conflict Between Explainable and Accountable Decision-Making Algorithms

May 11, 2022

Abstract:Decision-making algorithms are being used in important decisions, such as who should be enrolled in health care programs and be hired. Even though these systems are currently deployed in high-stakes scenarios, many of them cannot explain their decisions. This limitation has prompted the Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) initiative, which aims to make algorithms explainable to comply with legal requirements, promote trust, and maintain accountability. This paper questions whether and to what extent explainability can help solve the responsibility issues posed by autonomous AI systems. We suggest that XAI systems that provide post-hoc explanations could be seen as blameworthy agents, obscuring the responsibility of developers in the decision-making process. Furthermore, we argue that XAI could result in incorrect attributions of responsibility to vulnerable stakeholders, such as those who are subjected to algorithmic decisions (i.e., patients), due to a misguided perception that they have control over explainable algorithms. This conflict between explainability and accountability can be exacerbated if designers choose to use algorithms and patients as moral and legal scapegoats. We conclude with a set of recommendations for how to approach this tension in the socio-technical process of algorithmic decision-making and a defense of hard regulation to prevent designers from escaping responsibility.

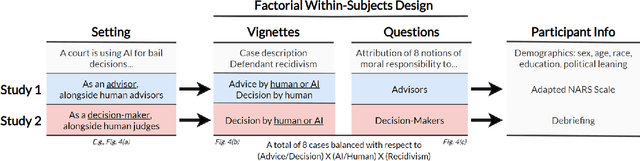

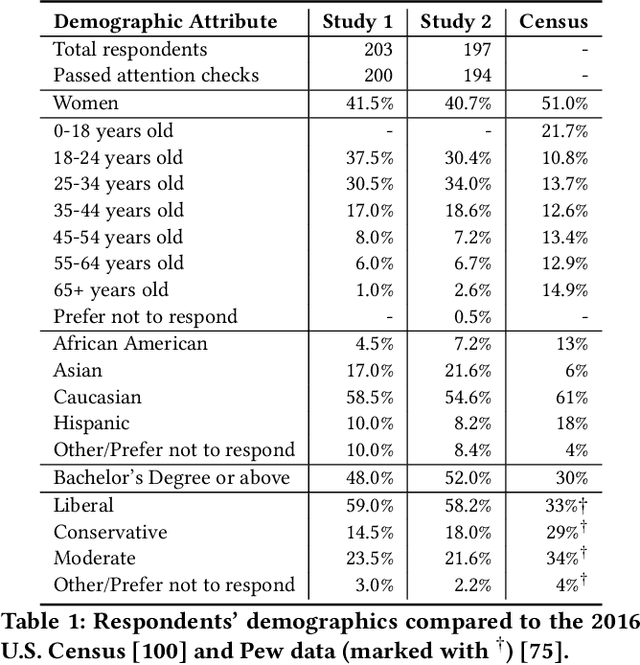

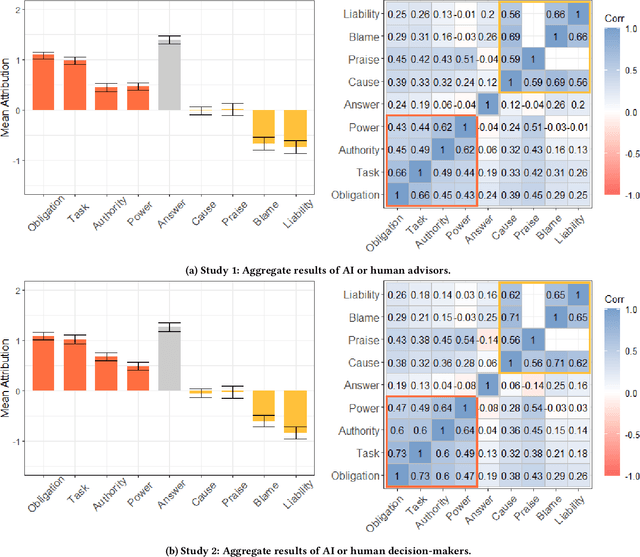

Human Perceptions on Moral Responsibility of AI: A Case Study in AI-Assisted Bail Decision-Making

Feb 01, 2021

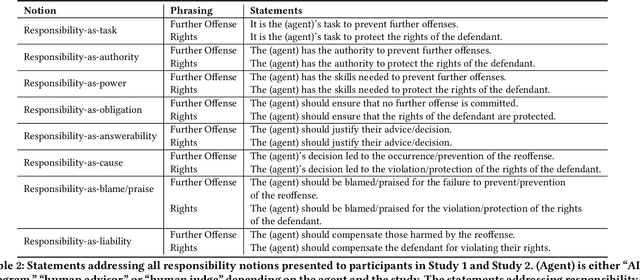

Abstract:How to attribute responsibility for autonomous artificial intelligence (AI) systems' actions has been widely debated across the humanities and social science disciplines. This work presents two experiments ($N$=200 each) that measure people's perceptions of eight different notions of moral responsibility concerning AI and human agents in the context of bail decision-making. Using real-life adapted vignettes, our experiments show that AI agents are held causally responsible and blamed similarly to human agents for an identical task. However, there was a meaningful difference in how people perceived these agents' moral responsibility; human agents were ascribed to a higher degree of present-looking and forward-looking notions of responsibility than AI agents. We also found that people expect both AI and human decision-makers and advisors to justify their decisions regardless of their nature. We discuss policy and HCI implications of these findings, such as the need for explainable AI in high-stakes scenarios.

Descriptive AI Ethics: Collecting and Understanding the Public Opinion

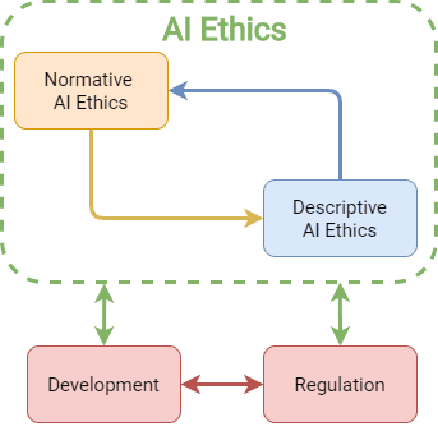

Jan 15, 2021

Abstract:There is a growing need for data-driven research efforts on how the public perceives the ethical, moral, and legal issues of autonomous AI systems. The current debate on the responsibility gap posed by these systems is one such example. This work proposes a mixed AI ethics model that allows normative and descriptive research to complement each other, by aiding scholarly discussion with data gathered from the public. We discuss its implications on bridging the gap between optimistic and pessimistic views towards AI systems' deployment.

Collecting the Public Perception of AI and Robot Rights

Aug 04, 2020

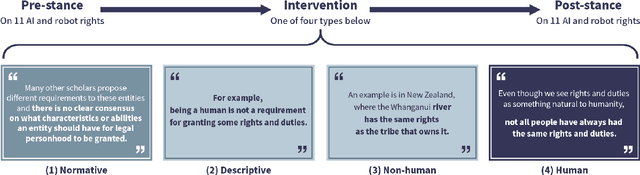

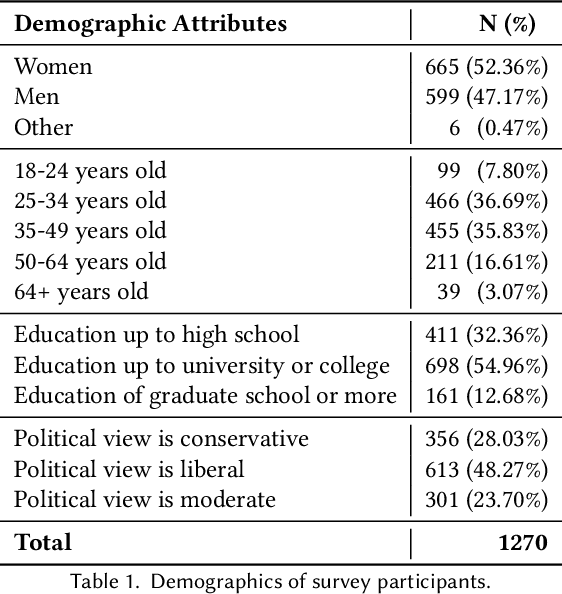

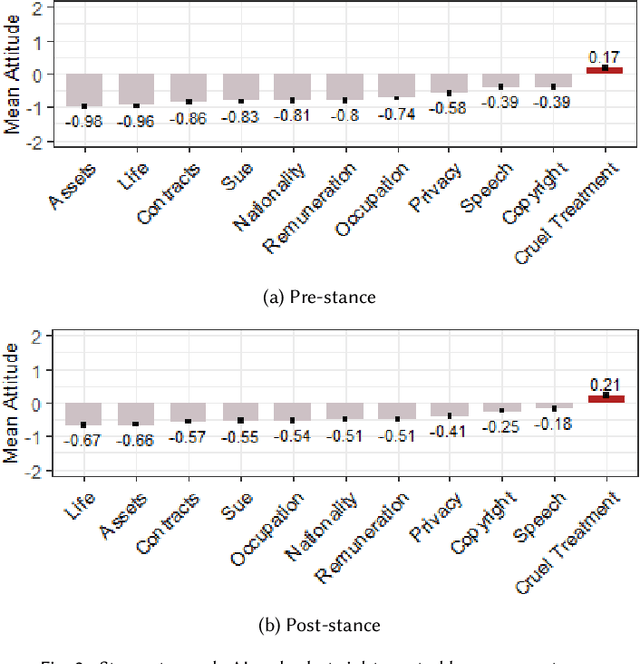

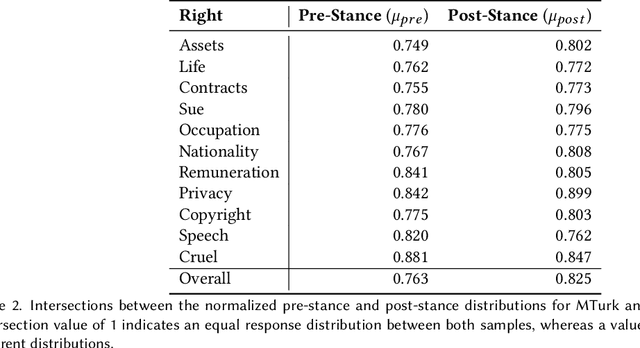

Abstract:Whether to give rights to artificial intelligence (AI) and robots has been a sensitive topic since the European Parliament proposed advanced robots could be granted "electronic personalities." Numerous scholars who favor or disfavor its feasibility have participated in the debate. This paper presents an experiment (N=1270) that 1) collects online users' first impressions of 11 possible rights that could be granted to autonomous electronic agents of the future and 2) examines whether debunking common misconceptions on the proposal modifies one's stance toward the issue. The results indicate that even though online users mainly disfavor AI and robot rights, they are supportive of protecting electronic agents from cruelty (i.e., favor the right against cruel treatment). Furthermore, people's perceptions became more positive when given information about rights-bearing non-human entities or myth-refuting statements. The style used to introduce AI and robot rights significantly affected how the participants perceived the proposal, similar to the way metaphors function in creating laws. For robustness, we repeated the experiment over a more representative sample of U.S. residents (N=164) and found that perceptions gathered from online users and those by the general population are similar.

Public Willingness to Get Vaccinated Against COVID-19: How AI-Developed Vaccines Can Affect Acceptance

Jul 03, 2020

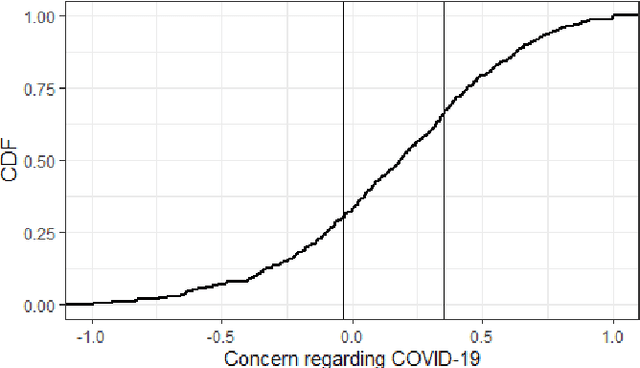

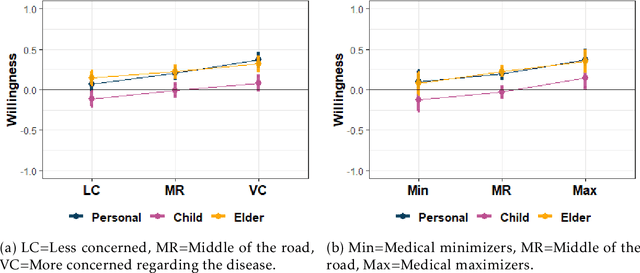

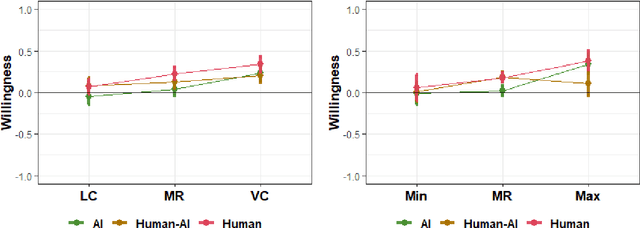

Abstract:Vaccines for COVID-19 are currently under clinical trials. These vaccines are crucial for eradicating the novel coronavirus. Despite the potential, there exist conspiracies related to vaccines online, which can lead to vaccination hesitancy and, thus, a longer-standing pandemic. We used a between-subjects study design (N=572 adults in the US and UK) to understand the public willingness towards vaccination against the novel coronavirus under various circumstances. Our survey findings suggest that people are more reluctant to vaccinate their children compared to themselves. Explicitly stating the high effectiveness of the vaccine against COVID-19 led to an increase in vaccine acceptance. Interestingly, our results do not indicate any meaningful variance due to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in developing vaccines, if these systems are described to be in use alongside human researchers. We discuss the public's expectation of local governments in assuring the safety and effectiveness of a future COVID-19 vaccine.

Responsible AI and Its Stakeholders

Apr 23, 2020Abstract:Responsible Artificial Intelligence (AI) proposes a framework that holds all stakeholders involved in the development of AI to be responsible for their systems. It, however, fails to accommodate the possibility of holding AI responsible per se, which could close some legal and moral gaps concerning the deployment of autonomous and self-learning systems. We discuss three notions of responsibility (i.e., blameworthiness, accountability, and liability) for all stakeholders, including AI, and suggest the roles of jurisdiction and the general public in this matter.

Explaining the Punishment Gap of AI and Robots

Mar 13, 2020

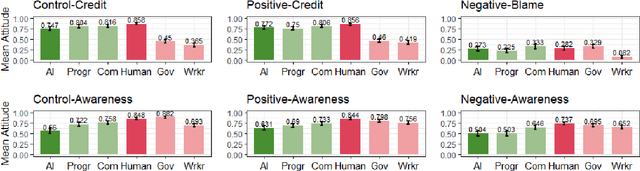

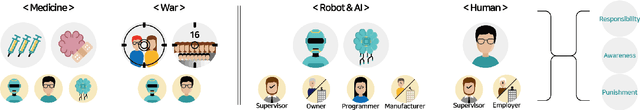

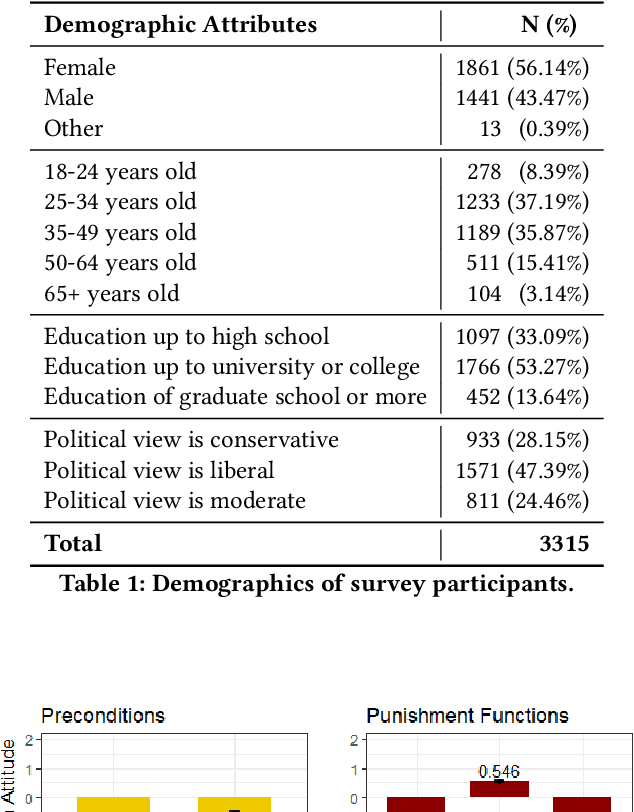

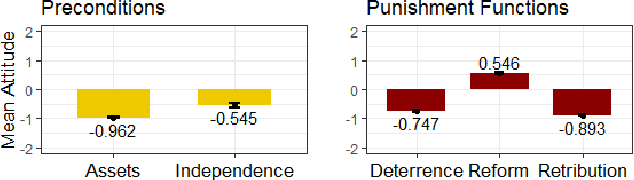

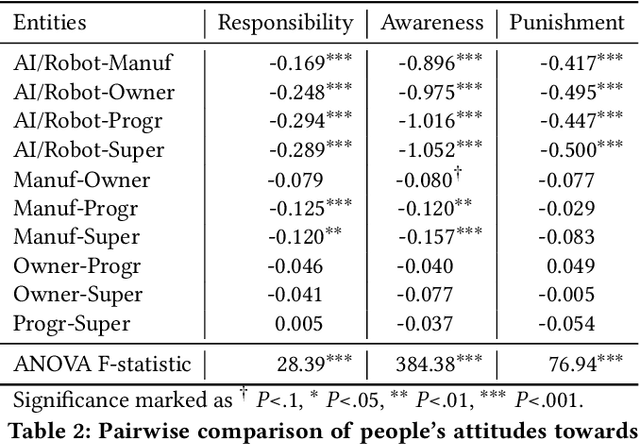

Abstract:The European Parliament's proposal to create a new legal status for artificial intelligence (AI) and robots brought into focus the idea of electronic legal personhood. This discussion, however, is hugely controversial. While some scholars argue that the proposed status could contribute to the coherence of the legal system, others say that it is neither beneficial nor desirable. Notwithstanding this prospect, we conducted a survey (N=3315) to understand online users' perceptions of the legal personhood of AI and robots. We observed how the participants assigned responsibility, awareness, and punishment to AI, robots, humans, and various entities that could be held liable under existing doctrines. We also asked whether the participants thought that punishing electronic agents fulfills the same legal and social functions as human punishment. The results suggest that even though people do not assign any mental state to electronic agents and are not willing to grant AI and robots physical independence or assets, which are the prerequisites of criminal or civil liability, they do consider them responsible for their actions and worthy of punishment. The participants also did not think that punishment or liability of these entities would achieve the primary functions of punishment, leading to what we define as the punishment gap. Therefore, before we recognize electronic legal personhood, we must first discuss proper methods of satisfying the general population's demand for punishment.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge