David Nieves

Learning Alternative Ways of Performing a Task

Apr 03, 2024Abstract:A common way of learning to perform a task is to observe how it is carried out by experts. However, it is well known that for most tasks there is no unique way to perform them. This is especially noticeable the more complex the task is because factors such as the skill or the know-how of the expert may well affect the way she solves the task. In addition, learning from experts also suffers of having a small set of training examples generally coming from several experts (since experts are usually a limited and expensive resource), being all of them positive examples (i.e. examples that represent successful executions of the task). Traditional machine learning techniques are not useful in such scenarios, as they require extensive training data. Starting from very few executions of the task presented as activity sequences, we introduce a novel inductive approach for learning multiple models, with each one representing an alternative strategy of performing a task. By an iterative process based on generalisation and specialisation, we learn the underlying patterns that capture the different styles of performing a task exhibited by the examples. We illustrate our approach on two common activity recognition tasks: a surgical skills training task and a cooking domain. We evaluate the inferred models with respect to two metrics that measure how well the models represent the examples and capture the different forms of executing a task showed by the examples. We compare our results with the traditional process mining approach and show that a small set of meaningful examples is enough to obtain patterns that capture the different strategies that are followed to solve the tasks.

* 32 pages, Github repository, published paper, authors' version

Fairness and Missing Values

May 29, 2019

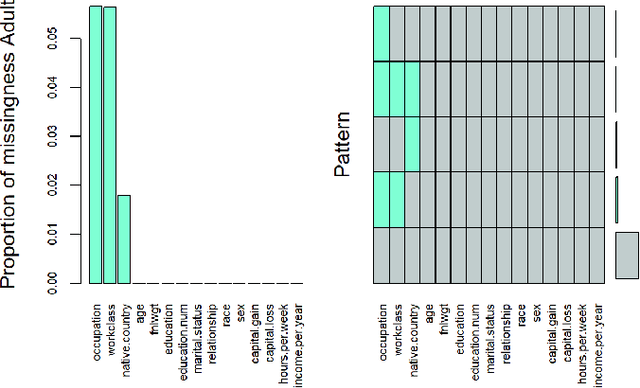

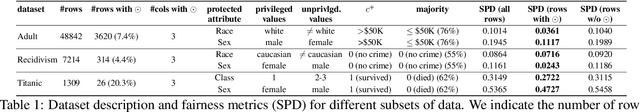

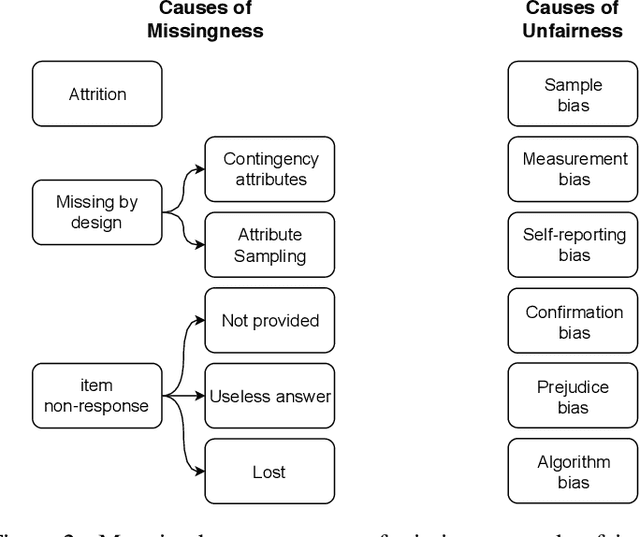

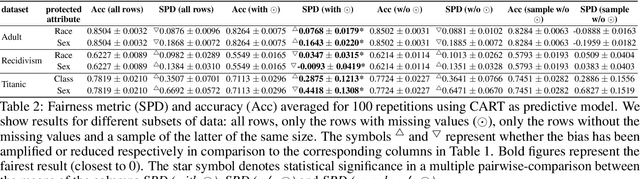

Abstract:The causes underlying unfair decision making are complex, being internalised in different ways by decision makers, other actors dealing with data and models, and ultimately by the individuals being affected by these decisions. One frequent manifestation of all these latent causes arises in the form of missing values: protected groups are more reluctant to give information that could be used against them, delicate information for some groups can be erased by human operators, or data acquisition may simply be less complete and systematic for minority groups. As a result, missing values and bias in data are two phenomena that are tightly coupled. However, most recent techniques, libraries and experimental results dealing with fairness in machine learning have simply ignored missing data. In this paper, we claim that fairness research should not miss the opportunity to deal properly with missing data. To support this claim, (1) we analyse the sources of missing data and bias, and we map the common causes, (2) we find that rows containing missing values are usually fairer than the rest, which should not be treated as the uncomfortable ugly data that different techniques and libraries get rid of at the first occasion, and (3) we study the trade-off between performance and fairness when the rows with missing values are used (either because the technique deals with them directly or by imputation methods). We end the paper with a series of recommended procedures about what to do with missing data when aiming for fair decision making.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge