Andrew W. Lo

AUTOCT: Automating Interpretable Clinical Trial Prediction with LLM Agents

Jun 04, 2025Abstract:Clinical trials are critical for advancing medical treatments but remain prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. Accurate prediction of clinical trial outcomes can significantly reduce research and development costs and accelerate drug discovery. While recent deep learning models have shown promise by leveraging unstructured data, their black-box nature, lack of interpretability, and vulnerability to label leakage limit their practical use in high-stakes biomedical contexts. In this work, we propose AutoCT, a novel framework that combines the reasoning capabilities of large language models with the explainability of classical machine learning. AutoCT autonomously generates, evaluates, and refines tabular features based on public information without human input. Our method uses Monte Carlo Tree Search to iteratively optimize predictive performance. Experimental results show that AutoCT performs on par with or better than SOTA methods on clinical trial prediction tasks within only a limited number of self-refinement iterations, establishing a new paradigm for scalable, interpretable, and cost-efficient clinical trial prediction.

LLM economicus? Mapping the Behavioral Biases of LLMs via Utility Theory

Aug 05, 2024

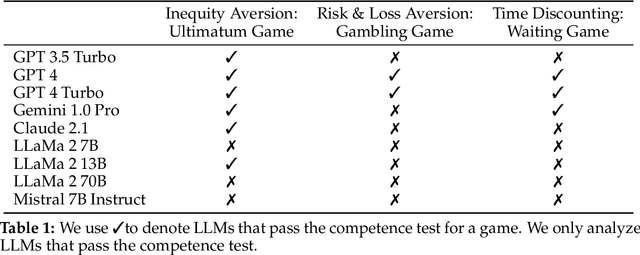

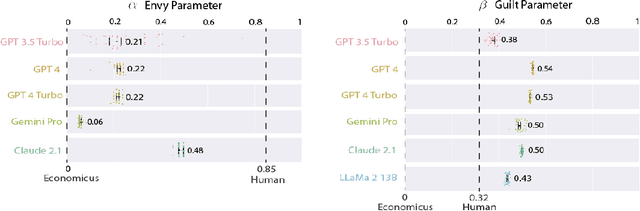

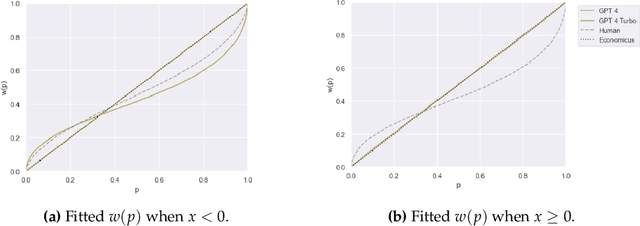

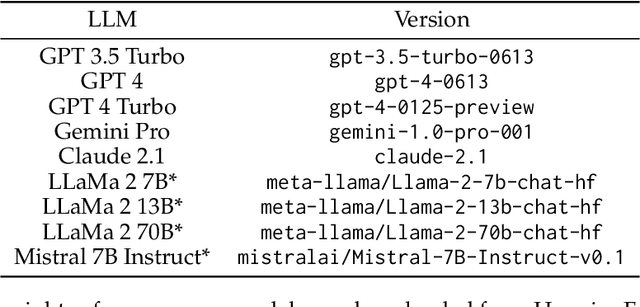

Abstract:Humans are not homo economicus (i.e., rational economic beings). As humans, we exhibit systematic behavioral biases such as loss aversion, anchoring, framing, etc., which lead us to make suboptimal economic decisions. Insofar as such biases may be embedded in text data on which large language models (LLMs) are trained, to what extent are LLMs prone to the same behavioral biases? Understanding these biases in LLMs is crucial for deploying LLMs to support human decision-making. We propose utility theory-a paradigm at the core of modern economic theory-as an approach to evaluate the economic biases of LLMs. Utility theory enables the quantification and comparison of economic behavior against benchmarks such as perfect rationality or human behavior. To demonstrate our approach, we quantify and compare the economic behavior of a variety of open- and closed-source LLMs. We find that the economic behavior of current LLMs is neither entirely human-like nor entirely economicus-like. We also find that most current LLMs struggle to maintain consistent economic behavior across settings. Finally, we illustrate how our approach can measure the effect of interventions such as prompting on economic biases.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge