Runshan Fu

Model Mis-specification and Algorithmic Bias

May 31, 2021

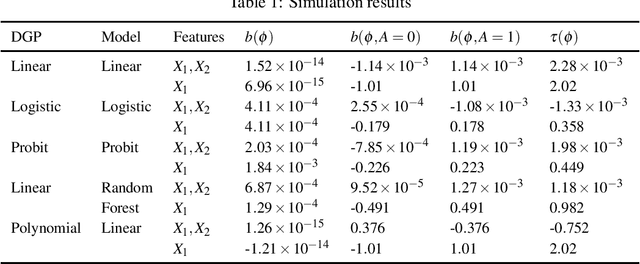

Abstract:Machine learning algorithms are increasingly used to inform critical decisions. There is a growing concern about bias, that algorithms may produce uneven outcomes for individuals in different demographic groups. In this work, we measure bias as the difference between mean prediction errors across groups. We show that even with unbiased input data, when a model is mis-specified: (1) population-level mean prediction error can still be negligible, but group-level mean prediction errors can be large; (2) such errors are not equal across groups; and (3) the difference between errors, i.e., bias, can take the worst-case realization. That is, when there are two groups of the same size, mean prediction errors for these two groups have the same magnitude but opposite signs. In closed form, we show such errors and bias are functions of the first and second moments of the joint distribution of features (for linear and probit regressions). We also conduct numerical experiments to show similar results in more general settings. Our work provides a first step for decoupling the impact of different causes of bias.

Crowd, Lending, Machine, and Bias

Jul 20, 2020

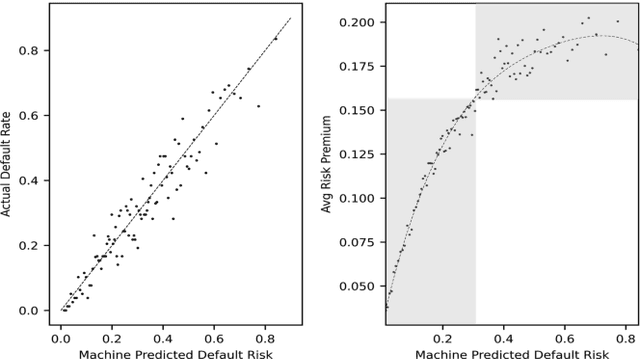

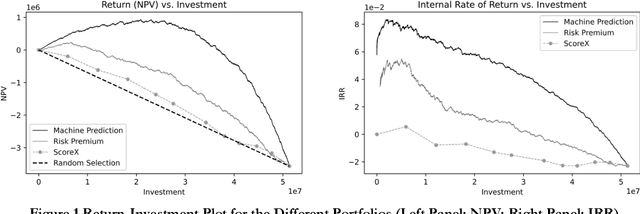

Abstract:Big data and machine learning (ML) algorithms are key drivers of many fintech innovations. While it may be obvious that replacing humans with machine would increase efficiency, it is not clear whether and where machines can make better decisions than humans. We answer this question in the context of crowd lending, where decisions are traditionally made by a crowd of investors. Using data from Prosper.com, we show that a reasonably sophisticated ML algorithm predicts listing default probability more accurately than crowd investors. The dominance of the machine over the crowd is more pronounced for highly risky listings. We then use the machine to make investment decisions, and find that the machine benefits not only the lenders but also the borrowers. When machine prediction is used to select loans, it leads to a higher rate of return for investors and more funding opportunities for borrowers with few alternative funding options. We also find suggestive evidence that the machine is biased in gender and race even when it does not use gender and race information as input. We propose a general and effective "debasing" method that can be applied to any prediction focused ML applications, and demonstrate its use in our context. We show that the debiased ML algorithm, which suffers from lower prediction accuracy, still leads to better investment decisions compared with the crowd. These results indicate that ML can help crowd lending platforms better fulfill the promise of providing access to financial resources to otherwise underserved individuals and ensure fairness in the allocation of these resources.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge