Francesco Corucci

Interoceptive robustness through environment-mediated morphological development

Jun 20, 2018

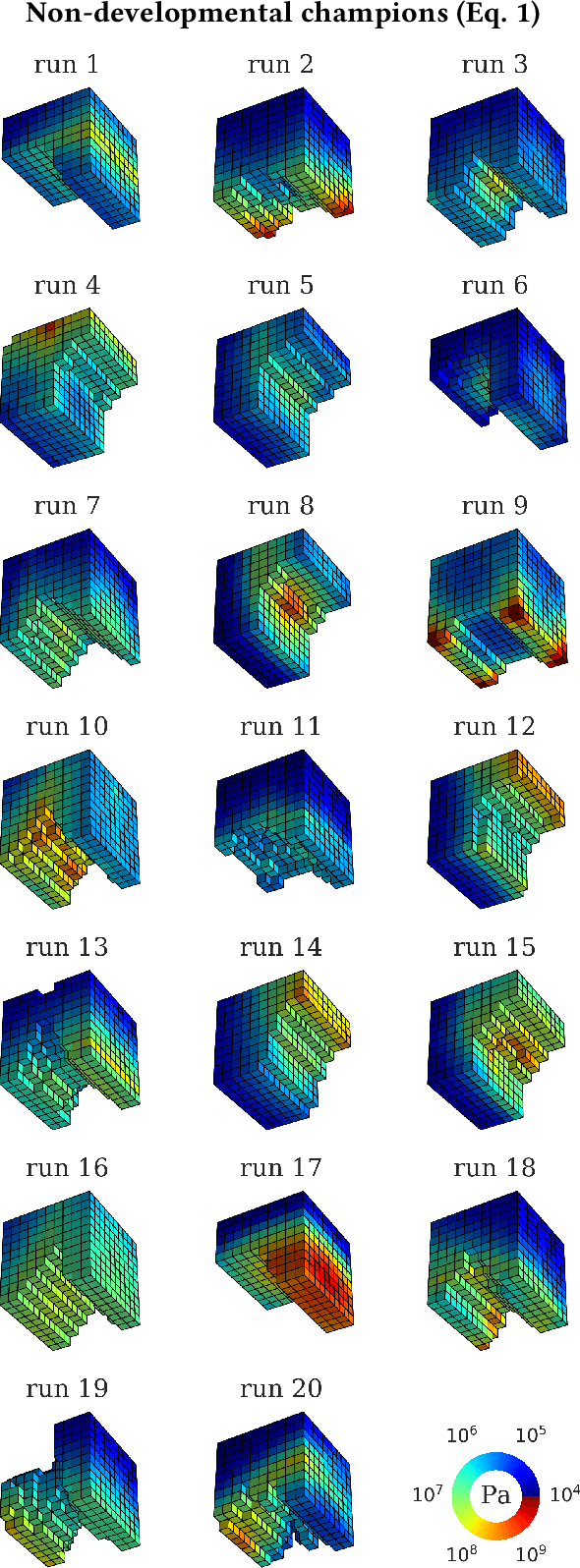

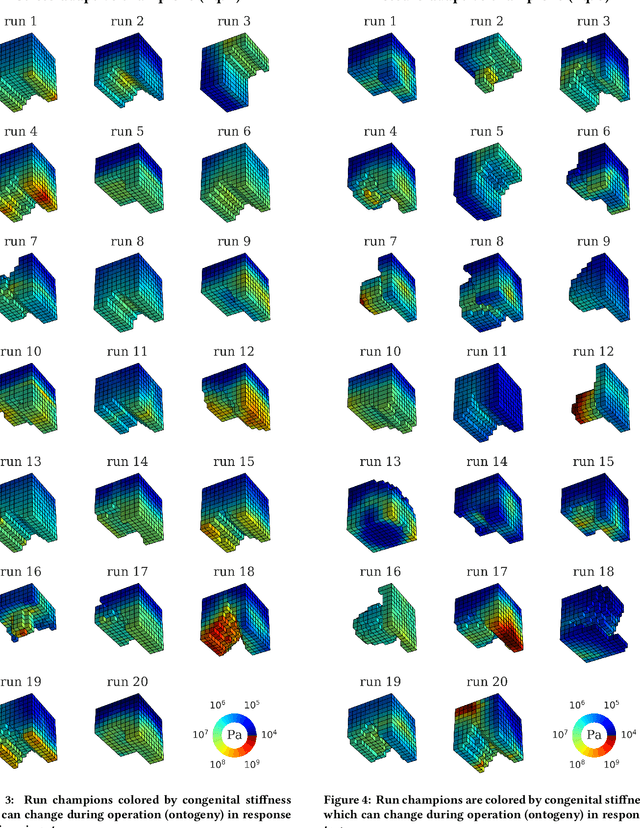

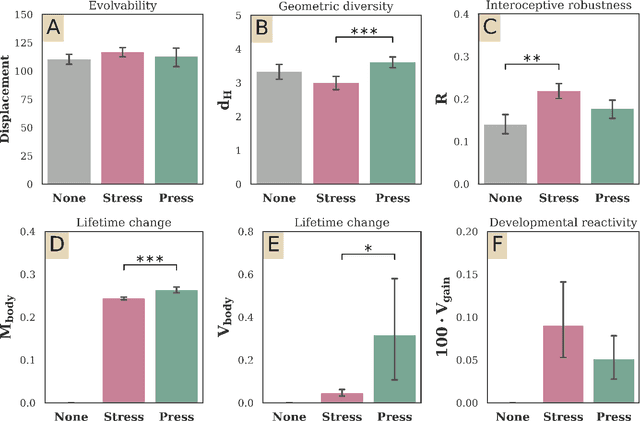

Abstract:Typically, AI researchers and roboticists try to realize intelligent behavior in machines by tuning parameters of a predefined structure (body plan and/or neural network architecture) using evolutionary or learning algorithms. Another but not unrelated longstanding property of these systems is their brittleness to slight aberrations, as highlighted by the growing deep learning literature on adversarial examples. Here we show robustness can be achieved by evolving the geometry of soft robots, their control systems, and how their material properties develop in response to one particular interoceptive stimulus (engineering stress) during their lifetimes. By doing so we realized robots that were equally fit but more robust to extreme material defects (such as might occur during fabrication or by damage thereafter) than robots that did not develop during their lifetimes, or developed in response to a different interoceptive stimulus (pressure). This suggests that the interplay between changes in the containing systems of agents (body plan and/or neural architecture) at different temporal scales (evolutionary and developmental) along different modalities (geometry, material properties, synaptic weights) and in response to different signals (interoceptive and external perception) all dictate those agents' abilities to evolve or learn capable and robust strategies.

Evolving soft locomotion in aquatic and terrestrial environments: effects of material properties and environmental transitions

Nov 17, 2017

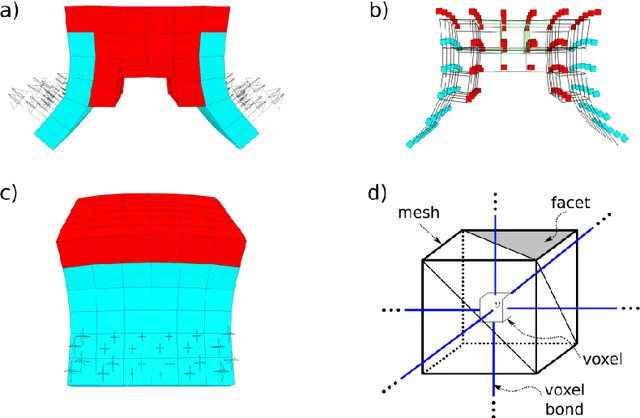

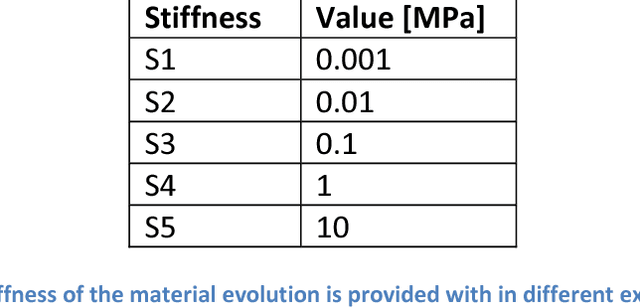

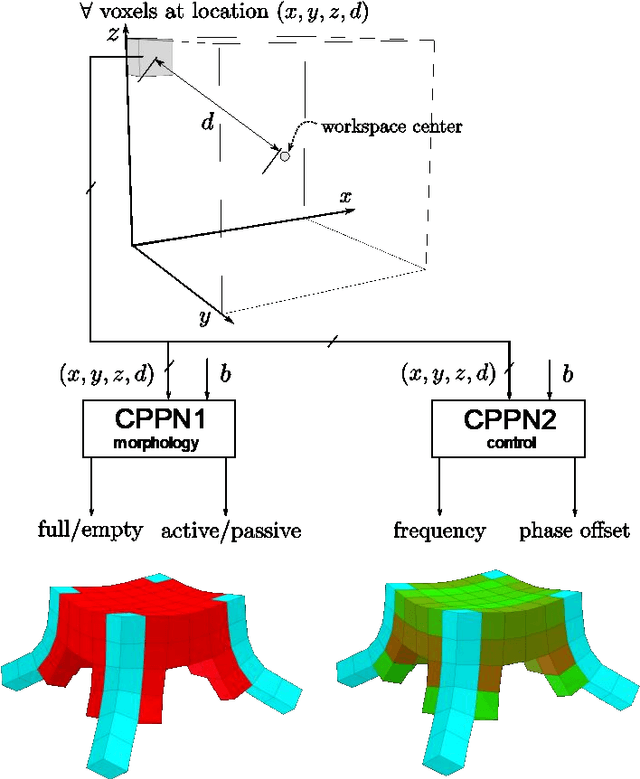

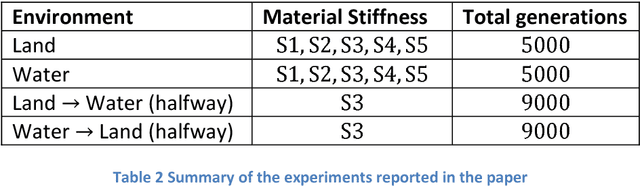

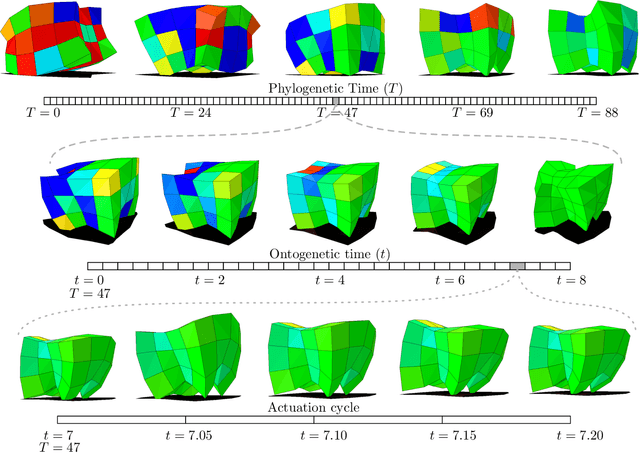

Abstract:Designing soft robots poses considerable challenges: automated design approaches may be particularly appealing in this field, as they promise to optimize complex multi-material machines with very little or no human intervention. Evolutionary soft robotics is concerned with the application of optimization algorithms inspired by natural evolution in order to let soft robots (both morphologies and controllers) spontaneously evolve within physically-realistic simulated environments, figuring out how to satisfy a set of objectives defined by human designers. In this paper a powerful evolutionary system is put in place in order to perform a broad investigation on the free-form evolution of walking and swimming soft robots in different environments. Three sets of experiments are reported, tackling different aspects of the evolution of soft locomotion. The first two sets explore the effects of different material properties on the evolution of terrestrial and aquatic soft locomotion: particularly, we show how different materials lead to the evolution of different morphologies, behaviors, and energy-performance tradeoffs. It is found that within our simplified physics world stiffer robots evolve more sophisticated and effective gaits and morphologies on land, while softer ones tend to perform better in water. The third set of experiments starts investigating the effect and potential benefits of major environmental transitions (land - water) during evolution. Results provide interesting morphological exaptation phenomena, and point out a potential asymmetry between land-water and water-land transitions: while the first type of transition appears to be detrimental, the second one seems to have some beneficial effects.

A Minimal Developmental Model Can Increase Evolvability in Soft Robots

Jun 22, 2017

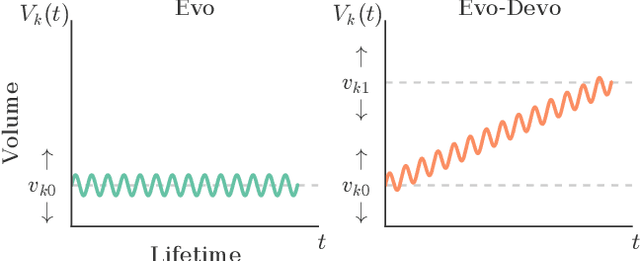

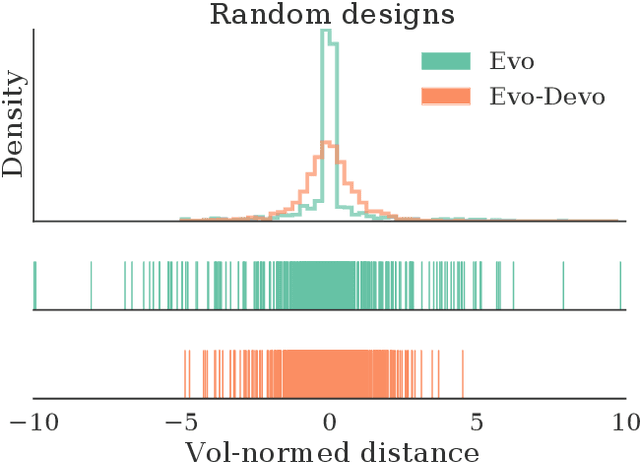

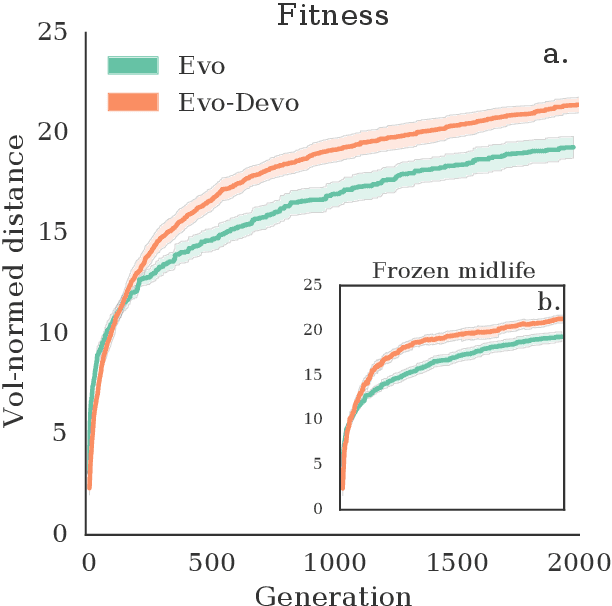

Abstract:Different subsystems of organisms adapt over many time scales, such as rapid changes in the nervous system (learning), slower morphological and neurological change over the lifetime of the organism (postnatal development), and change over many generations (evolution). Much work has focused on instantiating learning or evolution in robots, but relatively little on development. Although many theories have been forwarded as to how development can aid evolution, it is difficult to isolate each such proposed mechanism. Thus, here we introduce a minimal yet embodied model of development: the body of the robot changes over its lifetime, yet growth is not influenced by the environment. We show that even this simple developmental model confers evolvability because it allows evolution to sweep over a larger range of body plans than an equivalent non-developmental system, and subsequent heterochronic mutations 'lock in' this body plan in more morphologically-static descendants. Future work will involve gradually complexifying the developmental model to determine when and how such added complexity increases evolvability.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge