Andre Lustosa

Optimizing Predictions for Very Small Data Sets: a case study on Open-Source Project Health Prediction

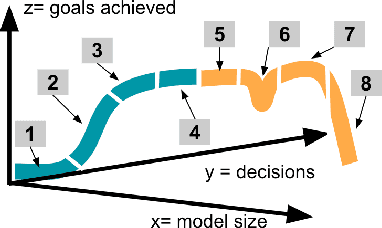

Jan 16, 2023Abstract:When learning from very small data sets, the resulting models can make many mistakes. For example, consider learning predictors for open source project health. The training data for this task may be very small (e.g. five years of data, collected every month means just 60 rows of training data). Using this data, prior work had unacceptably large errors in their learned predictors. We show that these high errors rates can be tamed by better configuration of the control parameters of the machine learners. For example, we present here a {\em landscape analytics} method (called SNEAK) that (a)~clusters the data to find the general landscape of the hyperparameters; then (b)~explores a few representatives from each part of that landscape. SNEAK is both faster and and more effective than prior state-of-the-art hyperparameter optimization algorithms (FLASH, HYPEROPT, OPTUNA, and differential evolution). More importantly, the configurations found by SNEAK had far less error that other methods. We conjecture that SNEAK works so well since it finds the most informative regions of the hyperparameters, then jumps to those regions. Other methods (that do not reflect over the landscape) can waste time exploring less informative options. From this, we make the following conclusions. Firstly, for predicting open source project health, we recommend landscape analytics (e.g.SNEAK). Secondly, and more generally, when learning from very small data sets, using hyperparameter optimization (e.g. SNEAK) to select learning control parameters. Due to its speed and implementation simplicity, we suggest SNEAK might also be useful in other ``data-light'' SE domains. To assist other researchers in repeating, improving, or even refuting our results, all our scripts and data are available on GitHub at https://github.com/zxcv123456qwe/niSneak

Fairer Software Made Easier (using "Keys")

Jul 11, 2021

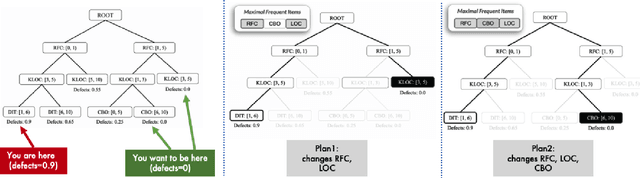

Abstract:Can we simplify explanations for software analytics? Maybe. Recent results show that systems often exhibit a "keys effect"; i.e. a few key features control the rest. Just to say the obvious, for systems controlled by a few keys, explanation and control is just a matter of running a handful of "what-if" queries across the keys. By exploiting the keys effect, it should be possible to dramatically simplify even complex explanations, such as those required for ethical AI systems.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge