The Emergence of the Shape Bias Results from Communicative Efficiency

Paper and Code

Sep 15, 2021

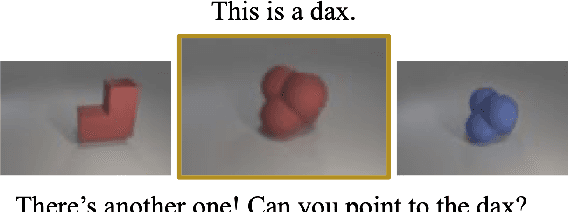

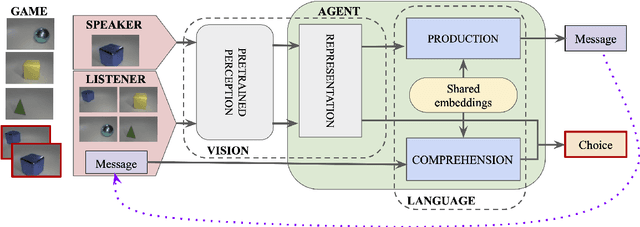

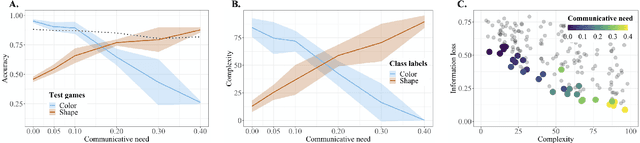

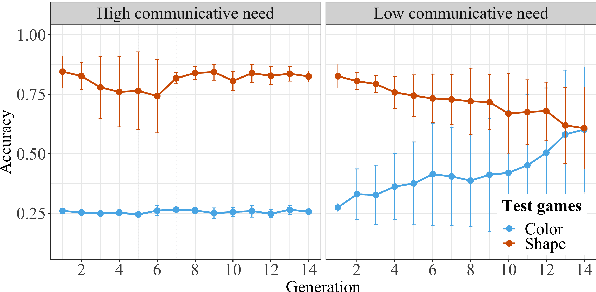

By the age of two, children tend to assume that new word categories are based on objects' shape, rather than their color or texture; this assumption is called the shape bias. They are thought to learn this bias by observing that their caregiver's language is biased towards shape based categories. This presents a chicken and egg problem: if the shape bias must be present in the language in order for children to learn it, how did it arise in language in the first place? In this paper, we propose that communicative efficiency explains both how the shape bias emerged and why it persists across generations. We model this process with neural emergent language agents that learn to communicate about raw pixelated images. First, we show that the shape bias emerges as a result of efficient communication strategies employed by agents. Second, we show that pressure brought on by communicative need is also necessary for it to persist across generations; simply having a shape bias in an agent's input language is insufficient. These results suggest that, over and above the operation of other learning strategies, the shape bias in human learners may emerge and be sustained by communicative pressures.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge