Comparing deep neural networks against humans: object recognition when the signal gets weaker

Paper and Code

Jun 21, 2017

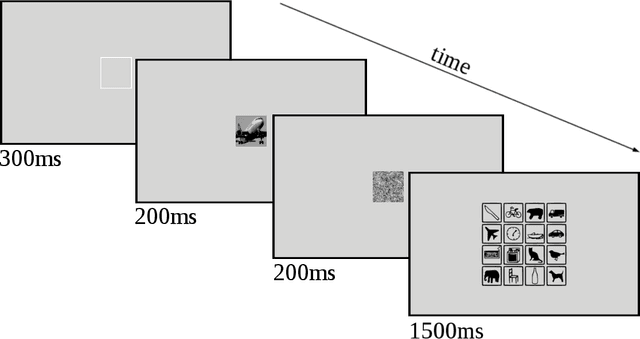

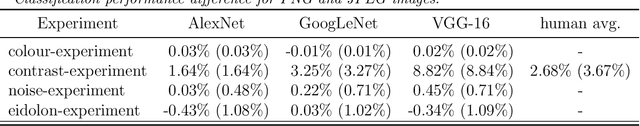

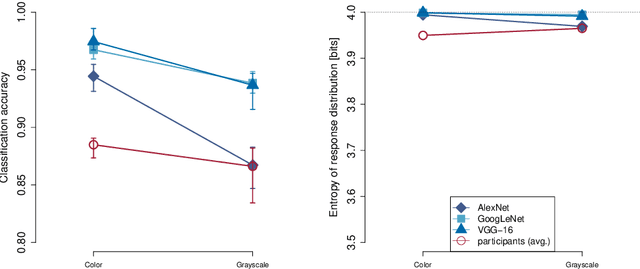

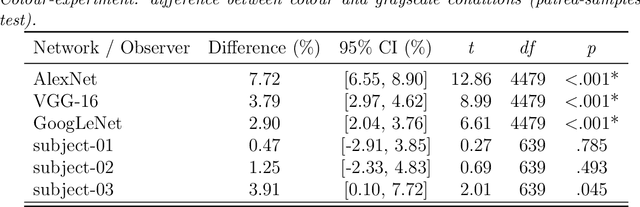

Human visual object recognition is typically rapid and seemingly effortless, as well as largely independent of viewpoint and object orientation. Until very recently, animate visual systems were the only ones capable of this remarkable computational feat. This has changed with the rise of a class of computer vision algorithms called deep neural networks (DNNs) that achieve human-level classification performance on object recognition tasks. Furthermore, a growing number of studies report similarities in the way DNNs and the human visual system process objects, suggesting that current DNNs may be good models of human visual object recognition. Yet there clearly exist important architectural and processing differences between state-of-the-art DNNs and the primate visual system. The potential behavioural consequences of these differences are not well understood. We aim to address this issue by comparing human and DNN generalisation abilities towards image degradations. We find the human visual system to be more robust to image manipulations like contrast reduction, additive noise or novel eidolon-distortions. In addition, we find progressively diverging classification error-patterns between man and DNNs when the signal gets weaker, indicating that there may still be marked differences in the way humans and current DNNs perform visual object recognition. We envision that our findings as well as our carefully measured and freely available behavioural datasets provide a new useful benchmark for the computer vision community to improve the robustness of DNNs and a motivation for neuroscientists to search for mechanisms in the brain that could facilitate this robustness.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge