Phanish Puranam

INSEAD

Can LLMs Help Improve Analogical Reasoning For Strategic Decisions? Experimental Evidence from Humans and GPT-4

May 01, 2025Abstract:This study investigates whether large language models, specifically GPT4, can match human capabilities in analogical reasoning within strategic decision making contexts. Using a novel experimental design involving source to target matching, we find that GPT4 achieves high recall by retrieving all plausible analogies but suffers from low precision, frequently applying incorrect analogies based on superficial similarities. In contrast, human participants exhibit high precision but low recall, selecting fewer analogies yet with stronger causal alignment. These findings advance theory by identifying matching, the evaluative phase of analogical reasoning, as a distinct step that requires accurate causal mapping beyond simple retrieval. While current LLMs are proficient in generating candidate analogies, humans maintain a comparative advantage in recognizing deep structural similarities across domains. Error analysis reveals that AI errors arise from surface level matching, whereas human errors stem from misinterpretations of causal structure. Taken together, the results suggest a productive division of labor in AI assisted organizational decision making where LLMs may serve as broad analogy generators, while humans act as critical evaluators, applying the most contextually appropriate analogies to strategic problems.

Why Trust in AI May Be Inevitable

Feb 28, 2025Abstract:In human-AI interactions, explanation is widely seen as necessary for enabling trust in AI systems. We argue that trust, however, may be a pre-requisite because explanation is sometimes impossible. We derive this result from a formalization of explanation as a search process through knowledge networks, where explainers must find paths between shared concepts and the concept to be explained, within finite time. Our model reveals that explanation can fail even under theoretically ideal conditions - when actors are rational, honest, motivated, can communicate perfectly, and possess overlapping knowledge. This is because successful explanation requires not just the existence of shared knowledge but also finding the connection path within time constraints, and it can therefore be rational to cease attempts at explanation before the shared knowledge is discovered. This result has important implications for human-AI interaction: as AI systems, particularly Large Language Models, become more sophisticated and able to generate superficially compelling but spurious explanations, humans may default to trust rather than demand genuine explanations. This creates risks of both misplaced trust and imperfect knowledge integration.

Tool or Tutor? Experimental evidence from AI deployment in cancer diagnosis

Feb 23, 2025

Abstract:Professionals increasingly use Artificial Intelligence (AI) to enhance their capabilities and assist with task execution. While prior research has examined these uses separately, their potential interaction remains underexplored. We propose that AI-driven training (tutor effect) and AI-assisted task completion (tool effect) can be complementary and test this hypothesis in the context of lung cancer diagnosis. In a field experiment with 334 medical students, we manipulated AI deployment in training, in practice, and in both. Our findings reveal that while AI-integrated training and AI assistance independently improved diagnostic performance, their combination yielded the highest accuracy. These results underscore AI's dual role in enhancing human performance through both learning and real-time support, offering insights into AI deployment in professional settings where human expertise remains essential.

Thinking with Many Minds: Using Large Language Models for Multi-Perspective Problem-Solving

Jan 04, 2025Abstract:Complex problem-solving requires cognitive flexibility--the capacity to entertain multiple perspectives while preserving their distinctiveness. This flexibility replicates the "wisdom of crowds" within a single individual, allowing them to "think with many minds." While mental simulation enables imagined deliberation, cognitive constraints limit its effectiveness. We propose synthetic deliberation, a Large Language Model (LLM)-based method that simulates discourse between agents embodying diverse perspectives, as a solution. Using a custom GPT-based model, we showcase its benefits: concurrent processing of multiple viewpoints without cognitive degradation, parallel exploration of perspectives, and precise control over viewpoint synthesis. By externalizing the deliberative process and distributing cognitive labor between parallel search and integration, synthetic deliberation transcends mental simulation's limitations. This approach shows promise for strategic planning, policymaking, and conflict resolution.

LLMs as mediators: Can they diagnose conflicts accurately?

Dec 19, 2024

Abstract:Prior research indicates that to be able to mediate conflict, observers of disagreements between parties must be able to reliably distinguish the sources of their disagreement as stemming from differences in beliefs about what is true (causality) vs. differences in what they value (morality). In this paper, we test if OpenAI's Large Language Models GPT 3.5 and GPT 4 can perform this task and whether one or other type of disagreement proves particularly challenging for LLM's to diagnose. We replicate study 1 in Ko\c{c}ak et al. (2003), which employes a vignette design, with OpenAI's GPT 3.5 and GPT 4. We find that both LLMs have similar semantic understanding of the distinction between causal and moral codes as humans and can reliably distinguish between them. When asked to diagnose the source of disagreement in a conversation, both LLMs, compared to humans, exhibit a tendency to overestimate the extent of causal disagreement and underestimate the extent of moral disagreement in the moral misalignment condition. This tendency is especially pronounced for GPT 4 when using a proximate scale that relies on concrete language specific to an issue. GPT 3.5 does not perform as well as GPT4 or humans when using either the proximate or the distal scale. The study provides a first test of the potential for using LLMs to mediate conflict by diagnosing the root of disagreements in causal and evaluative codes.

Learning what they think vs. learning what they do: The micro-foundations of vicarious learning

Jul 31, 2020

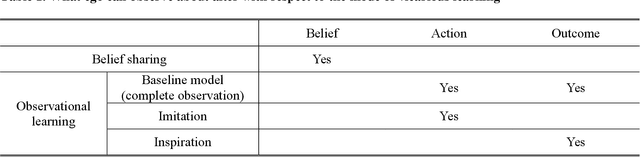

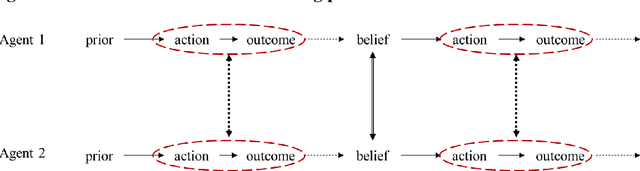

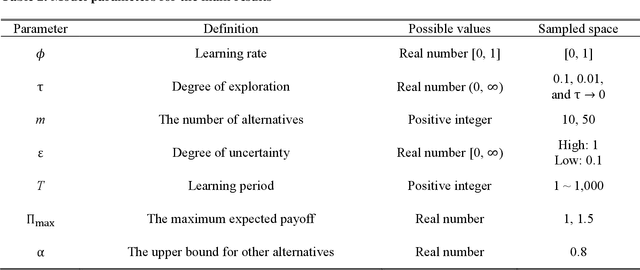

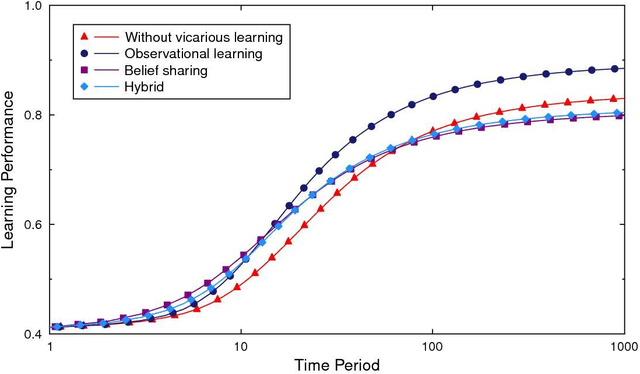

Abstract:Vicarious learning is a vital component of organizational learning. We theorize and model two fundamental processes underlying vicarious learning: observation of actions (learning what they do) vs. belief sharing (learning what they think). The analysis of our model points to three key insights. First, vicarious learning through either process is beneficial even when no agent in a system of vicarious learners begins with a knowledge advantage. Second, vicarious learning through belief sharing is not universally better than mutual observation of actions and outcomes. Specifically, enabling mutual observability of actions and outcomes is superior to sharing of beliefs when the task environment features few alternatives with large differences in their value and there are no time pressures. Third, symmetry in vicarious learning in fact adversely affects belief sharing but improves observational learning. All three results are shown to be the consequence of how vicarious learning affects self-confirming biased beliefs.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge